The 1927 Volume I of The Octagon Library of Early American Architecture focuses on Charleston, South Carolina. The volume is  edited by two notable Charleston architects, Albert Simons and Samuel Lapham, Jr., and goes into thorough detail on the architecture and history of Charleston.

edited by two notable Charleston architects, Albert Simons and Samuel Lapham, Jr., and goes into thorough detail on the architecture and history of Charleston.

In the preface, Samuel Gaillard Stoney introduces Charleston as a place that “preserved the tradition of the classic, with its intellectual freedom, its moral tolerance, its discipline in matters of etiquette, its individualism, and the spirit of logic which elsewhere largely perished in the romantic movement” (pg. 11). Typical of the 1920s South, Stoney refers to “systematized negro labor” and explains that “malaria made the negro the agricultural laborer exclusively,” thereby blatantly ignoring the realities of slavery (pg. 11-12). He concludes his brief history of Charleston with an explanation that “if these people did nothing else worthy of memorial, they set up in their city records of a society and a civilization, drawn from an older time” (pg. 13).

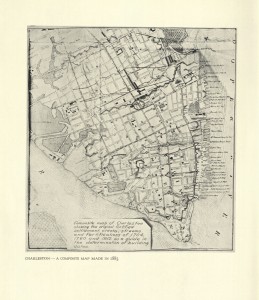

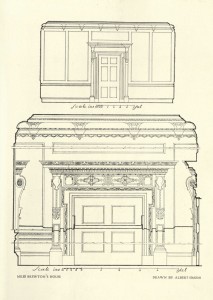

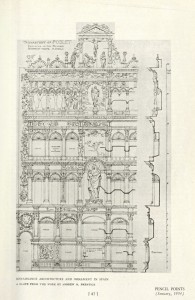

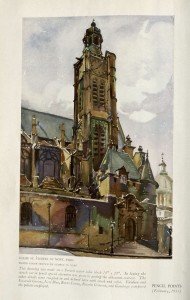

Simons and Lapham’s study moves chronologically from the founding of Charleston in 1670 to the ante-bellum  period and includes many photographs of local buildings, sectional drawing plans, and city plans for Charleston. Despite the French Hugeunot presence in early Charleston, “it is difficult to point out anything that is indisputably Gallic, for what is not English has rather more of a Dutch character” (pg. 17). The staple crops of the area were rice and indigo, and many in the area amassed fortunes as planters. Following the American revolution, during which Charleston was heavily damaged as a focal point of the fighting, there occurred “the erection of a considerable number of religious, philanthropic, and social institutions, as well as commercial and domestic buildings” (pg. 103). There also was more French influence in the architecture, as well as English, and greater ingenuity in the designs (for example, in the oval drawing-rooms, and a focus on size rather than detail).

period and includes many photographs of local buildings, sectional drawing plans, and city plans for Charleston. Despite the French Hugeunot presence in early Charleston, “it is difficult to point out anything that is indisputably Gallic, for what is not English has rather more of a Dutch character” (pg. 17). The staple crops of the area were rice and indigo, and many in the area amassed fortunes as planters. Following the American revolution, during which Charleston was heavily damaged as a focal point of the fighting, there occurred “the erection of a considerable number of religious, philanthropic, and social institutions, as well as commercial and domestic buildings” (pg. 103). There also was more French influence in the architecture, as well as English, and greater ingenuity in the designs (for example, in the oval drawing-rooms, and a focus on size rather than detail).

Of equal interest is a note on the title page of the book from one of the authors: “To the successors of Paul P. Cret from Albert Simons in grateful appreciation of our Cher Maitre.” Simons also signed the book right above his name. Cret was the architect of the Tower and campus at UT Austin, drawing an interesting connection between two figures who greatly influenced the cities of Charleston and Austin.

The Octagon Library: Charleston, South Carolina is more pictures and drawings than writing, but the images demonstrate the elements the authors mention and give a better sense of Charleston’s architecture. Charleston has grown in popularity over recent years, and become renowned for its  well-preserved buildings, history, and Southern charm. While other Southern cities have failed to protect their historic homes and buildings, Charleston has capitalized on them. The city also beautifully shows how historic events shape the identity of a place. The destruction of Charleston during the American Revolution followed by a fire and heavy artillery damages during the Civil War have resulted in Charleston placing an emphasis on protecting its buildings. Many cities could learn from Charleston’s example. The inclination toward tearing down old homes to make room for businesses may seem practical, but integrating those old buildings into the fabric of local society and industry has been financially rewarding for Charleston. So, why invest in protecting historic buildings? Just ask Charleston – it’s on fire again, just not that kind of fire.

well-preserved buildings, history, and Southern charm. While other Southern cities have failed to protect their historic homes and buildings, Charleston has capitalized on them. The city also beautifully shows how historic events shape the identity of a place. The destruction of Charleston during the American Revolution followed by a fire and heavy artillery damages during the Civil War have resulted in Charleston placing an emphasis on protecting its buildings. Many cities could learn from Charleston’s example. The inclination toward tearing down old homes to make room for businesses may seem practical, but integrating those old buildings into the fabric of local society and industry has been financially rewarding for Charleston. So, why invest in protecting historic buildings? Just ask Charleston – it’s on fire again, just not that kind of fire.

Harney explores the history, landscape, architecture, and intellectual background of Horace Walpole’s villa, Strawberry Hill. She evaluates “the villa and the landscape…as an entity” and argues that “Strawberry Hill embodies an entirely different set of ideas [from nineteenth-century Gothic Revival] to which the key lies in the cultural pursuits and theories of imaginative pleasure that Walpole engaged with” (pg. xiv). Harney makes use of Walpole’s writing and the historical context to alter conceptions of Walpole’s inspiration for Strawberry Hill, as well as to consider the setting of the villa as a crucial component of its architecture and identity.

Harney explores the history, landscape, architecture, and intellectual background of Horace Walpole’s villa, Strawberry Hill. She evaluates “the villa and the landscape…as an entity” and argues that “Strawberry Hill embodies an entirely different set of ideas [from nineteenth-century Gothic Revival] to which the key lies in the cultural pursuits and theories of imaginative pleasure that Walpole engaged with” (pg. xiv). Harney makes use of Walpole’s writing and the historical context to alter conceptions of Walpole’s inspiration for Strawberry Hill, as well as to consider the setting of the villa as a crucial component of its architecture and identity. discussed “the relationship of places to each other, their architecture, and their experience with memory” and “the position of contemporary architecture in the historic urban landscape” (pg. ix). The articles themselves cover a wide array of subjects, including management strategies for urban areas, innovation in Italian architecture in the twentieth-century, conservation, and case studies. Almost all directly discuss Sarajevo or Bosnia and Herzegovina, creating an ideal environment for the attendees to discuss and consider the challenges of Sarajevo in particular: a fifteenth-century city ravaged by war from 1992-1995, now adapting and seeking to blend its history with modern needs.

discussed “the relationship of places to each other, their architecture, and their experience with memory” and “the position of contemporary architecture in the historic urban landscape” (pg. ix). The articles themselves cover a wide array of subjects, including management strategies for urban areas, innovation in Italian architecture in the twentieth-century, conservation, and case studies. Almost all directly discuss Sarajevo or Bosnia and Herzegovina, creating an ideal environment for the attendees to discuss and consider the challenges of Sarajevo in particular: a fifteenth-century city ravaged by war from 1992-1995, now adapting and seeking to blend its history with modern needs.

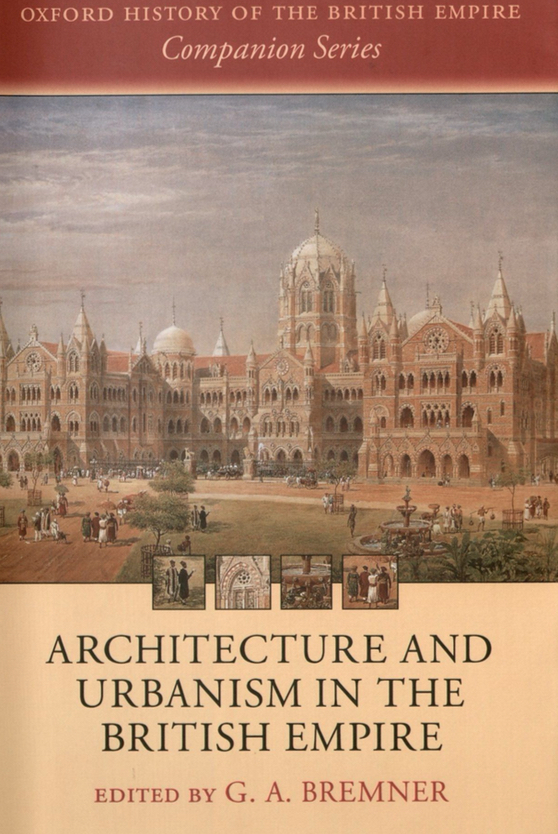

Dr. G. A. Bremner presents the first comprehensive resource on architecture and urban planning in the British Empire in this companion to the Oxford History of the British Empire. The survey spans from thematic elements of imperial and colonial architecture to the specific implementation of those plans, as well as the “local variation” of architecture across the Empire. Bremner writes in the introduction, “colonialism was all but impossible without the buildings and spaces that articulated its presence…this naturally has consequences for how any post-colonial nation state imagines both its past and future” (pg. 1-2).

Dr. G. A. Bremner presents the first comprehensive resource on architecture and urban planning in the British Empire in this companion to the Oxford History of the British Empire. The survey spans from thematic elements of imperial and colonial architecture to the specific implementation of those plans, as well as the “local variation” of architecture across the Empire. Bremner writes in the introduction, “colonialism was all but impossible without the buildings and spaces that articulated its presence…this naturally has consequences for how any post-colonial nation state imagines both its past and future” (pg. 1-2).