Many remember Hal Box as an architect, dean, and visionary for architectural education, but Hal was also a great champion of libraries. He had a keen understanding that strong architecture programs are built on solid foundations. For Hal, this foundation included an architecture library, close at hand, where students and faculty could browse and check out books.

In January 2010, we were busily preparing for the School of Architecture centennial. As the school’s library, we were in effect preparing for our own grand anniversary, so I asked Hal if he wouldn’t mind providing an oral history. He graciously agreed and this is how I learned about Hal’s love and respect for libraries.

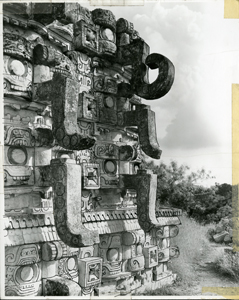

Hal’s experience with libraries started in early childhood when he attended East Texas State Teacher’s College training school for his elementary education. He lived two blocks from campus and on his walk home would stop at the college library. Hal described this building as similar to the University of Texas’ first library, Battle Hall, with a grand stairway leading to the second floor reading room. Hal spent many hours doing his homework in this space, and received great encouragement from its librarian.

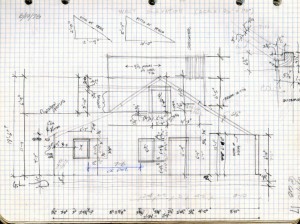

In the late 1950s, as a young professional working with James Pratt, Hal became interested in developing a firm library, explaining “There were no architecture schools in Dallas and the public library didn’t have much on architecture.” Hal gained an early understanding of both the value and cost of an architecture library, as the firm spent a lot of money on journals. They built this library in their conference room and he even had his son catalog it! “That was really the first library I built.”

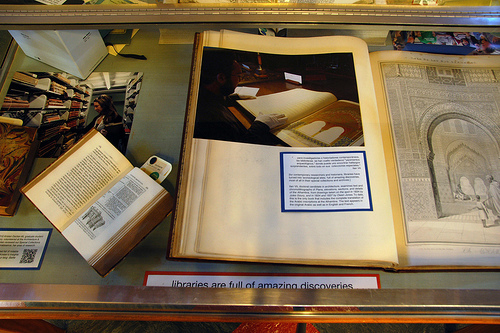

In 1971 Hal started the architecture school at UT Arlington in a small house off campus. It was about a quarter mile walk from the main library to the studio and the architecture books were shelved throughout three floors, so it was very difficult for them to use. A gift from the father of faculty member Peter Woods- a collection of grand Beaux Arts folios- inspired Hal to transform a small classroom into a library for his school. He obtained a $1,000 grant from the Texas Society of Architects and started to build the collection. His unorthodox collection plan also consisted of each faculty member checking out the maximum number of books from the main University Library and reshelving them all in his new library. The Head Librarian found out about it and called Hal. Hal recalled his response:

“Why don’t you come over and we’ll talk about it. He [the librarian] was just as angry as could be. I told him this is what we’re going to do. Architecture was not like history or English where you check out a book and in two weeks you read it. You want to browse through a whole lot of books, it’s mainly visual, and you had to be close to them because you want to use them while you are in studio. You’re not going to check them out for a week and take them home. You’re going to go over to the library and look up Aalto or Corbu and see how they did something and then proceed from there. Well then, he understood and we continued there.”

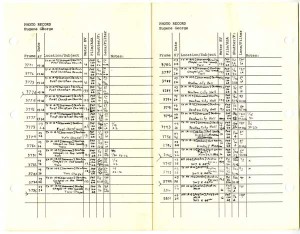

Hal secured a new building for the program and made sure that its design included both a library and slide collection. It was his good fortune that the director of the Fort Worth Museum of Art was married to a librarian, so he quickly hired her to oversee the library. “I think it was about that time we convinced the general library to establish a branch library.” (Hal then decided to “hire a young PhD from Berkeley” to help develop the library and slide collection. These collections were so important that despite not having money to bring him in for an interview, Hal hired Jay Henry sight unseen to conduct this work.)

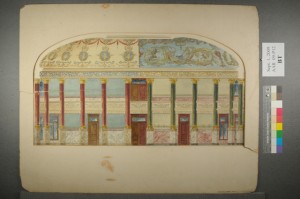

In 1976, during his interview for Dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Texas, Hal and a friend visited the Battle Hall library, which then housed a variety of subjects including architecture and planning. Earlier in 1973, architecture’s collections were transferred to Battle Hall. Hal and his friend compared their experiences as students using the architecture library. Hal’s library had a dedicated librarian and was just doors away from his studio, while his frustrated friend couldn’t find (browse) any architecture books because they were mixed in with other non-architecture subjects. Hal soon learned that there was great discussion of consolidating branch libraries into the Perry Casteñeda Library when it would open in 1977, further dispersing the services and collections from its School.

In preparation of his meeting with UT President Lorene Rogers, Hal made a list of what the School needed, specifying the necessity its own branch library. Hal believe that “the library is more than just a bunch of books, it’s a place with services.” As part of his signing agreement, Battle Hall and Sutton became part of the School of Architecture’s campus when he became Dean. Hal continued to make it a priority to keep the library close by. In 1980, Battle Hall became home to the Architecture & Planning Library branch and the architectural drawings collection, now known as the Alexander Architectural Archive.

During this time, Hal initiated the renovation of the buildings on his architecture campus. Hal decided not to continue with the Battle Hall renovation because among other things, it would have displaced too much valuable stacks space. Even in my last meeting with Hal, he still struggled with the renovation of the University’s first library building.

“Libraries are sources of power… that knowledge they hold is power.” As Dean, Hal understood the constraints of a library budget and that the library did not have its own alumni from which to draw support. Also in his experience, the school could not recruit against Harvard because it didn’t have the research collections to support scholarship.

“One of my objectives, after I realized that this needed to be more than a professional school… [was that] it needed to involve the whole discipline of architecture- so we’re not just training professionals, we’re developing scholars… we’re developing people who will be active within the community. So it really started when we signed our first PhD… [and began] building a collection that would be vital to scholars. It was a very distinct objective to make this happen in the school, and that, just like a scientist… he’s got to have a laboratory. [If we could achieve this] we would be a major source for scholarship, and I think that has happened.”

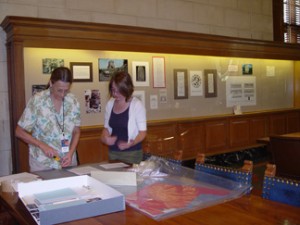

As a member of the library council, Hal motioned for and pushed through a library fee for each student. He knew that it wasn’t much, but it helped a bit. Hal was also very hands-on with the library and archive. He chuckled when he told me about how he and Molly Malone single handedly moved the drawings from Blake Alexander’s closet in Goldsmith to Battle Hall, in preparation for the Goldsmith renovation. Through his many contacts, Hal was also instrumental in helping to obtain archival collections such as that of Howard Meyer, or Harwell Hamilton Harris, or finding funding for the purchase of the James Riely Gordon collection among others. As Dean, he even funded the early curators and until his death he was serving on the University of Texas Libraries Advisory Council.

More recently, Hal was enthusiastic about new technologies for teaching and research. He enjoyed learning about the great online resources the library offers, while at the same time found that there is still relatively very little published digitally in architecture. As Hal was preparing to close down his office at the School of Architecture, he offered the papers and books he had amassed over the years to the Architecture & Planning Library. We are grateful that we had the chance to thank him and to let him know how valuable many of these books will be to our collections.

From childhood, Hal was inspired by the architecture of libraries and their librarians, as a professional, he valued a firm library, and as a scholar he built his own personal library. For the University of Texas, he started and developed a branch library from the ground up in Arlington and in Austin secured a strong branch research library and archive close to his School. Hal understood and valued libraries from all perspectives. One of his fondest memories was in the library as a University of Texas architecture student in 1946. “Most students concentrated near the recent periodicals. They went there right away when they got a design problem. It was a good place. It was a happy place.”