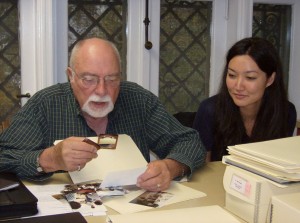

Think of historic preservation in Texas and you think of Wayne Bell. So when my Introduction to Archival Enterprise group was assigned to process the papers Bell donated to the Alexander Architectural Archive, we were thrilled to have the opportunity to interview the UT professor emeritus who was instrumental in founding the historic preservation master’s degree program.

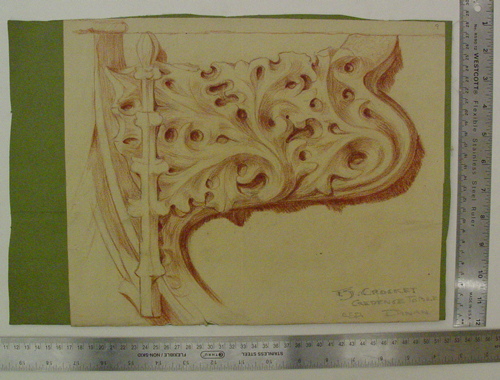

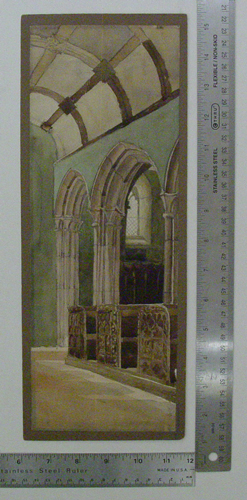

When organizing an individual’s papers, you hope that they left enough reports, notes, photographs, and more to be able to piece together a story, to understand the person and his or her work. Bell had—for projects like the Inge-Stoneham House (1982-1987) and its relocation as part of the Winedale Historical Center program, we discovered day-to-day memoranda of contractor decisions, in addition to numerous photographs and other documentation. However, there also were many unlabeled contact sheets, research files without a clear project affiliation, and other records that only Bell could explain to us.

What we learned in chatting with Bell was even more revealing—while he showed remarkable powers of recollection about 40-year-old photos, there were a few photos and documents in the Wayne Bell papers that even Wayne Bell couldn’t explain. Sometimes an archivist just has to make an educated guess about a record and how it fits into the narrative—and hope that researchers will be able to complete the story.