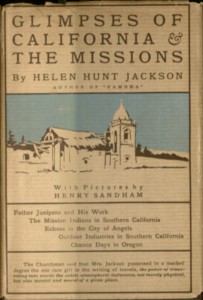

Glimpses of California & The Missions by Helen Hunt Jackson, published originally in 1883, explores the California Mission system, paying particular attention to the history and current status of Native Americans in the Missions, and contemporary life in the state. Jackson provides a thorough recounting of the history of the Missions mixed with the stories and conversations she heard along her journey through California.

Glimpses of California & The Missions by Helen Hunt Jackson, published originally in 1883, explores the California Mission system, paying particular attention to the history and current status of Native Americans in the Missions, and contemporary life in the state. Jackson provides a thorough recounting of the history of the Missions mixed with the stories and conversations she heard along her journey through California.

Jackson focuses on Father Junipero Serra, the condition of Mission Indians, Los Angeles, outdoor industries, and includes a short chapter on her visit to Oregon. Throughout Glimpses of California & The Missions are drawings by Henry Sandham, which portray the scenery and the people they came across, as well as historical figures like Father Junipero. Jackson devotes a great deal of the book to describing the unfair and, she argues, illegal treatment of Native Americans, especially in regards to the ownership of their land. She describes one case where Temecula Indians were anxious “as to the title to their lands…all that was in existence to show that they had any was the protecting clause in an old Mexican grant” (pg. 116). After years of uncertainty and arguments, the case went to court. The Temecula “appealed to the Catholic bishop to help them…but the scheme had been too skillfully plotted” (pg. 116). When the Sheriffs arrived to forcibly remove the Indians from the land, Jackson notes that “the Indians’ first impulse was as determined as it could have been if they had been white, to resist the outrage,” but that this was an unacceptable response and would likely lead to violence (pg. 119). So, the Temecula did not resist, but instead staged a sit-in of sorts: they refused to resist the Sheriff, but also refused to help them. Interestingly, Jackson openly delineates the racial prejudice involved in this treatment, a fact which was widely known but rarely acknowledged. In sum, Glimpses of California & The Missions provides valuable insight into the state of California and its history, with Jackson additionally using the book to advocate for Native Americans.

Just as notable as the book itself is  the life of its author, Helen Hunt Jackson. A well-known author of the Nineteenth Century, Jackson’s most famous work remains her novel, Ramona, a fictionalized telling of Native American life in the 1800s, focusing on United States government’s poor treatment of Native Americans and the racial prejudice faced by mixed race individuals. Jackson also wrote A Century of Dishonor, a carefully researched book which revealed how the federal government reneged on treaties and promises made with tribes. She became a leading advocate for better treatment of Native Americans, and was even hired by the Interior Department to visit Missions in California and write a report on the conditions of the “Mission Indians” who lived there, a trip which inspired Glimpses of California & The Missions. This book was written somewhat concurrently with Ramona and the two books make similar arguments about the poor treatment of Native Americans, but are entirely different genres. Yet Ramona was far more widely read than Glimpses of California & The Missions, and the novel has drawn comparisons with Harriet Beacher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin for its use of fiction to portray harsh realities and unveil injustices.

the life of its author, Helen Hunt Jackson. A well-known author of the Nineteenth Century, Jackson’s most famous work remains her novel, Ramona, a fictionalized telling of Native American life in the 1800s, focusing on United States government’s poor treatment of Native Americans and the racial prejudice faced by mixed race individuals. Jackson also wrote A Century of Dishonor, a carefully researched book which revealed how the federal government reneged on treaties and promises made with tribes. She became a leading advocate for better treatment of Native Americans, and was even hired by the Interior Department to visit Missions in California and write a report on the conditions of the “Mission Indians” who lived there, a trip which inspired Glimpses of California & The Missions. This book was written somewhat concurrently with Ramona and the two books make similar arguments about the poor treatment of Native Americans, but are entirely different genres. Yet Ramona was far more widely read than Glimpses of California & The Missions, and the novel has drawn comparisons with Harriet Beacher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin for its use of fiction to portray harsh realities and unveil injustices.

In essence, Glimpses of California & The Missions is a scholarly attempt, through some primary sources, some oral histories, and Jackson’s own eyewitness account, to draw attention to the treatment of Native Americans. But where Glimpses of California failed to capture the public’s attention, Ramona succeeded beyond even Jackson’s expectations: there have been more than 300 printings since the book’s original publication in 1884, and five feature film adaptations. Embedded within Ramona‘s pages, amongst the romance and tragedy of its eponymous heroine’s story is Jackson’s political, radical (for the time) message. Although racism remains a persistent problem to this day on many Native American reservations, Jackson singlehandedly revealed the dishonorable conduct of the federal government towards Native Americans, creating an outrage that forced the government to change its practices. Jackson, Glimpses of California & The Missions, Ramona, and A Century of Dishonor provide an important lesson in activism and demonstrate the power of books in enacting change. Activists (primarily men, it is important to note) had tried for years to draw attention to the struggles of Native Americans across the country, but ultimately, it was Helen Hunt Jackson and her pen that held the United States government to task and began a process towards justice.

Originally published in 1931, John Gloag’s book

Originally published in 1931, John Gloag’s book

(pg. 14). The fact that Wright, as early as 1932, made a point of including women apprentices is fascinating, even somewhat radical. Today, many still note an excess of gender discrimination in the field of architecture, as well as a dearth of female architects. In contrast, Wright dedicated 40% of the apprenticeships to ensuring women had opportunities. While there may have been no follow-through on this goal (Wright notes that he has decreased the number of fellows to 70 and mentions that the fellowship would likely be only 30% girls), there are letters to female apprentices throughout the collection. It is worthwhile to note that Wright offers less praise for his female students than his male students, sometimes merely relegating them to “furnish” a project or “housebreak the owners” (pg. 96). He also proves somewhat haughty at times, such as after a student left Taliesin, telling him, “we all make errors of judgment, if we have any judgment, and being a young fellow, you ought to acquire a collection of errors in your own name as I have in mine,” indicating that he believes the student’s abandonment of Taliesin to be a mistake he will later regret (pg. 97). Wright also showed himself through the letters to be dedicated to keeping up with his pupils, often offering them work or advice, and asking about their families and personal lives. While Wright definitely showed a preference for his male students, he remained a loyal correspondent with many of his students whom he respected.

(pg. 14). The fact that Wright, as early as 1932, made a point of including women apprentices is fascinating, even somewhat radical. Today, many still note an excess of gender discrimination in the field of architecture, as well as a dearth of female architects. In contrast, Wright dedicated 40% of the apprenticeships to ensuring women had opportunities. While there may have been no follow-through on this goal (Wright notes that he has decreased the number of fellows to 70 and mentions that the fellowship would likely be only 30% girls), there are letters to female apprentices throughout the collection. It is worthwhile to note that Wright offers less praise for his female students than his male students, sometimes merely relegating them to “furnish” a project or “housebreak the owners” (pg. 96). He also proves somewhat haughty at times, such as after a student left Taliesin, telling him, “we all make errors of judgment, if we have any judgment, and being a young fellow, you ought to acquire a collection of errors in your own name as I have in mine,” indicating that he believes the student’s abandonment of Taliesin to be a mistake he will later regret (pg. 97). Wright also showed himself through the letters to be dedicated to keeping up with his pupils, often offering them work or advice, and asking about their families and personal lives. While Wright definitely showed a preference for his male students, he remained a loyal correspondent with many of his students whom he respected.

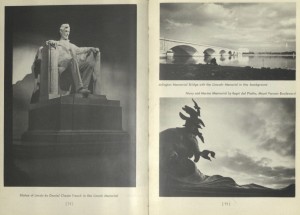

placed the most important buildings on hills, so as to make them prominent and add to the dignity and celebration of democracy. Washington D.C. “was a desolate and dreary place [in 1800 when the government first moved]…but with each emergency in the national life, the Federal City grew and developed” (pg. 14). The following chapter focuses on the Capitol building, the Supreme Court, the Library of Congress, the White House, and other notable buildings, making particular note of the configuration and centralization of the most important institutions of the government in a relatively small area of the city. Much of the rest of the book is comprised of photographs related to other aspects of Washington life including the buildings and areas deemed most important. These photos show embassies, historic homes, festivals, and the landscape of the area.

placed the most important buildings on hills, so as to make them prominent and add to the dignity and celebration of democracy. Washington D.C. “was a desolate and dreary place [in 1800 when the government first moved]…but with each emergency in the national life, the Federal City grew and developed” (pg. 14). The following chapter focuses on the Capitol building, the Supreme Court, the Library of Congress, the White House, and other notable buildings, making particular note of the configuration and centralization of the most important institutions of the government in a relatively small area of the city. Much of the rest of the book is comprised of photographs related to other aspects of Washington life including the buildings and areas deemed most important. These photos show embassies, historic homes, festivals, and the landscape of the area.