The Webb collection includes of over 700 documents, including architectural drawings, “tearsheets”, photographs, sketches, doodles and presentation pieces. Sir Aston Webb worked as an architect in London during the Victorian and Edwardian eras, and was responsible for the design of many public buildings and monuments. This important collection was transferred to us through The Harry Ransom Center in 1983.

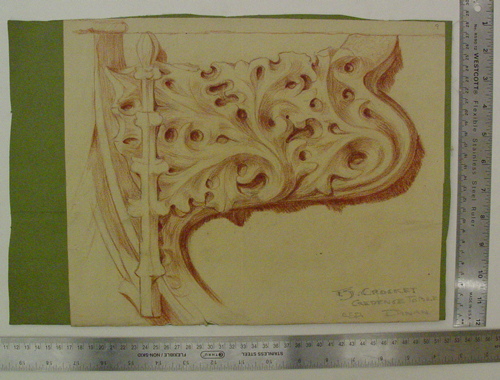

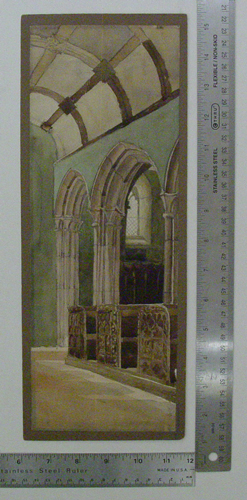

These images offer interesting insights into the working process of Sir Aston Webb. Many of the drawings have hand-written notes, corrections and annotation scribbled on them. We have a few literal back-of-the-napkin calculations and ideas, as well as very rough conceptual sketches. It is this kind of evidence which brings us closer to history and the people who built the world we live in today.

Working with two iSchool volunteers, Ana Cox and Ashley Butler, our primary responsibility was to create digital images of each item in this collection to allow eventual digital access, but along the way we also re-housed some items and performed some minor conservation on others. The re-housing was performed to keep the smaller items from sliding around in large drawers, and also to allow for more efficient storage. We encountered several jewels which our images, though accurate, fail to do justice to. A big part of this project, for me, was the increased appreciation of the artistic value of these supposedly technical drawings.

Most of the conservation performed was simple surface cleaning. While it may seem elementary to clean a dirty document, some important considerations must be acknowledged. First, the cleaning is abrasive to the surface of the document, and so should only be carried out on those objects sturdy enough to withstand it. The method of surface cleaning must also be considered, as some are more effective, and more potentially damaging, than others. Finally, time has to be taken into account. Each item must be cleaned front and back.

Cleaning by itself might seem to some to be of little importance, especially when the document being cleaned has a huge tear running through it. However, dirt can do damage in a number of ways. Small particles can be sharp, and as one object slides against another these particles can scrape the paper, damaging and weakening it. Also, dirt can attract pests which eat paper. Paper by itself can be food to some insects, but dirty paper is delicious food. Dirt obscures details, warps our perception of color, and can easily be transferred from one object to another through careless handling or just through contact. Dirt can include pollutants from the air, which in this case means that our collection was coated in a thin layer of Victorian London’s industrial smog. I’m not sure exactly what such smog was made up of, but I am confident that chemicals harmful to paper, such as sulfur and chlorine, were in the mix.

This during-treatment image of some surface cleaning gives an idea of how a simple treatment can have a dramatic effect. The left side has been surface cleaned with soot sponges, while the right has yet to be worked on.

Assessment of a collection is a necessary step, but it is only one step in the life of a collection at an institution. It is sandwiched between accessioning on the one side and re-housing and conservation on the other, and even that simplification fails to take into account the previous and future life of the collection. Our assessment was not only able to tell us what we had, but where it was, what its condition was, how it was treated before it came to us and how we could best treat it in the future. Owning a collection is not simply a matter of keeping it in drawers, but is an active and thoughtful process that should be managed with care and consideration.