Thomas Morris. A House for the Suburbs; Socially and Architecturally Sketched. London: All Booksellers, 1860.

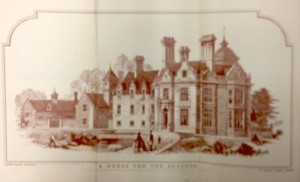

The spine of this book simply proclaimed, A House for the Suburbs., and drew my attention. I expected to open the cover and find mid-century modern; however, I discovered this:

According to Thomas Morris: Thanks to the modern Genius of Speed and the Science of Rail, a wholesome future is in store for us. (pg. 1) The ease and speed of traveling between London and its environs has made it possible to live outside the city and reap the benefits of suburban living- gardens and improved health. He describes the suburbs of London and moves on to a discussion of the social expectations of suburban life: picnics, dinner parties, and book club.

Morris than transitions into a discussion of the architectural history of houses. He proclaims:

Very distinct is modern society from that of former periods; very superior our condition in regard to the security of property and person; and altogether unprecedented our rapidity of location; -yet the character of our dwellings is, or ought to be, equally distinguishable from those of any previous age.

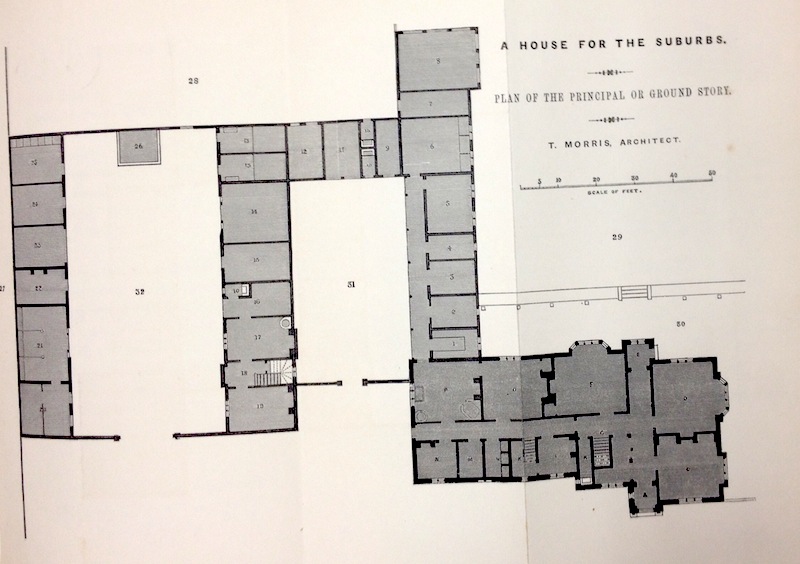

He concludes with a discussion on “The Suburban House exemplified,” which includes the topics of style, material, and spaces.