Hello. It’s Abbie again, back with another installment on processing and publishing the Volz & Associates, Inc. collection. I recently had the opportunity to present on this collection at The University of Texas’ 2019 Digital Preservation Symposium, where I discussed some of my solutions to born-digital access and preservation issues.

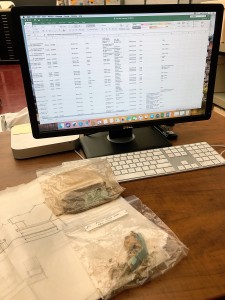

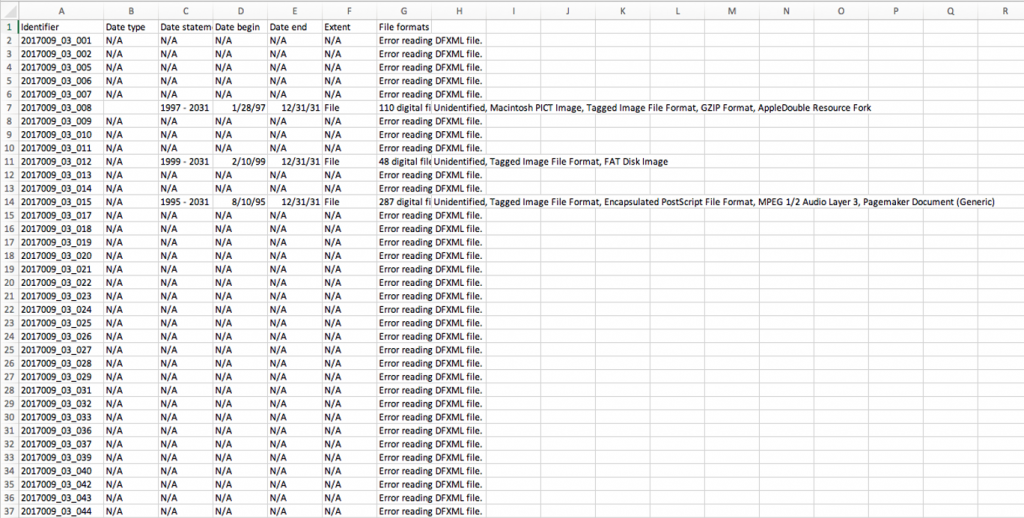

In the course of processing this collection, some of the most significant roadblocks were related to problematic disk images and metadata generation. These revolved around two distinct media types: zip disks and CDs. The collection contains 85 inventoried zip disks. When these were imaged and analyzed in BitCurator, the report came back riddled with error messages. Even though the disk images had been generated successfully, something was keeping fiwalk from generating the correct metadata. This made it impossible to determine necessary information like disk extent, content, and the presence of possible PII or malware.

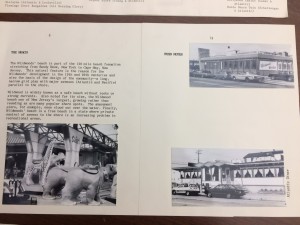

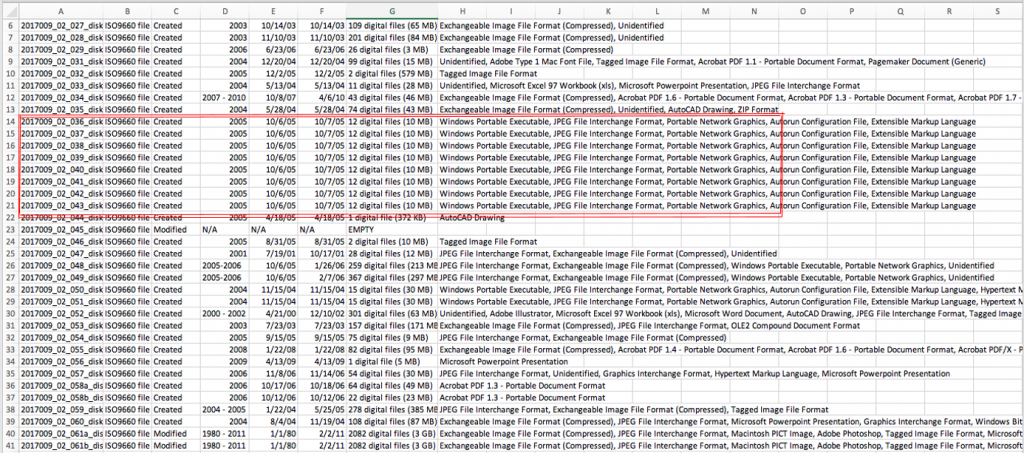

When processing CDs, I noticed a group of about a dozen disks each had the exact same metadata. While some similarities are expected, I thought it was strange that that many disks from different projects could each have identical specs. I analyzed the disk images and physical disks and found that they were all CDs of photos processed by the same company. The original content of the disks had been overwritten by the company’s built-in structural and technical metadata, making the disk images virtually useless for research purposes. However, when these disks were mounted in FTK Imager, a write-blocked environment, it became clear that the original images were still extant – they just weren’t being picked up in the disk images.

In both of these cases, I knew that the original content could be reached but didn’t know how to access it while adhering to the best practices set up by both the digital archiving community and the resources at my disposal. The disks with these issues amounted to nearly 1/5 of the imaged collection, and many hours of research and testing were put into how I could reprocess this information. Ultimately, I found myself faced with a choice – I could either preserve inaccurate representations of the disk by retaining the existing disk images or preserve inaccurate representations of the metadata by extracting extant files instead of preserving a disk image. The issue with preserving the metadata as it stood was that it was wrong to begin with, and the resources at hand didn’t provide a solution.

When thinking about how best to reprocess this information, I was drawn to this quote from a study undertaken by Julia Kim, the Digital Assets Manager at the Library of Congress:

“Most of the researchers emphasized that if it came to partially processed files or emulations and a significant time delay in processing, they would take unprocessed and relatively inauthentic files. Access by any means, and ease of access were stressed by the majority.”

“Researcher Interactions with Born-Digital: Out of the Frying Pan and into the Reading Room,” saaers.wordpress.com

While we certainly don’t want to prioritize patron opinion over archival standards, this quote made me question whether sacrificing access and preservation to retain imperfect metadata could truly be considered “best practice.”

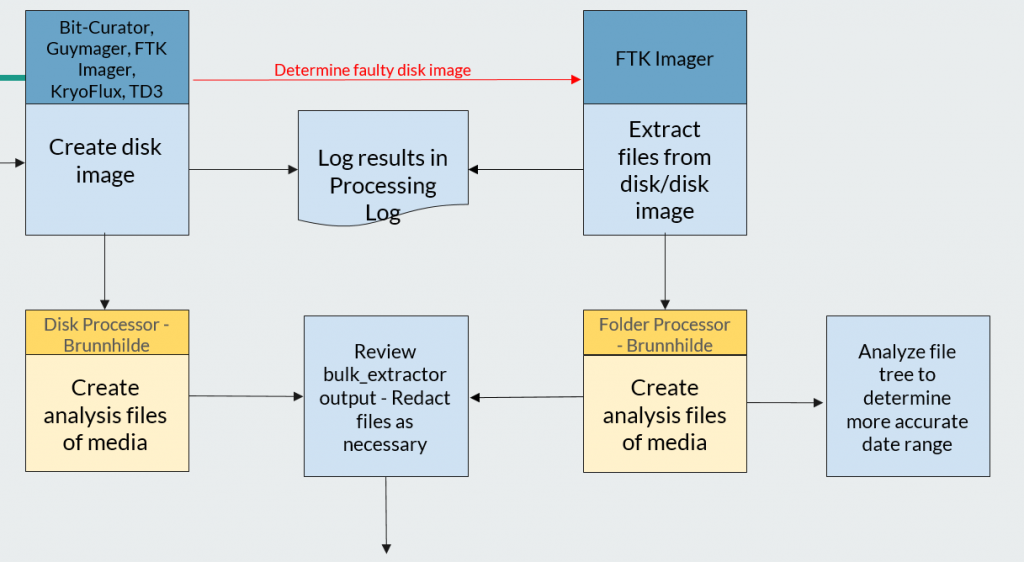

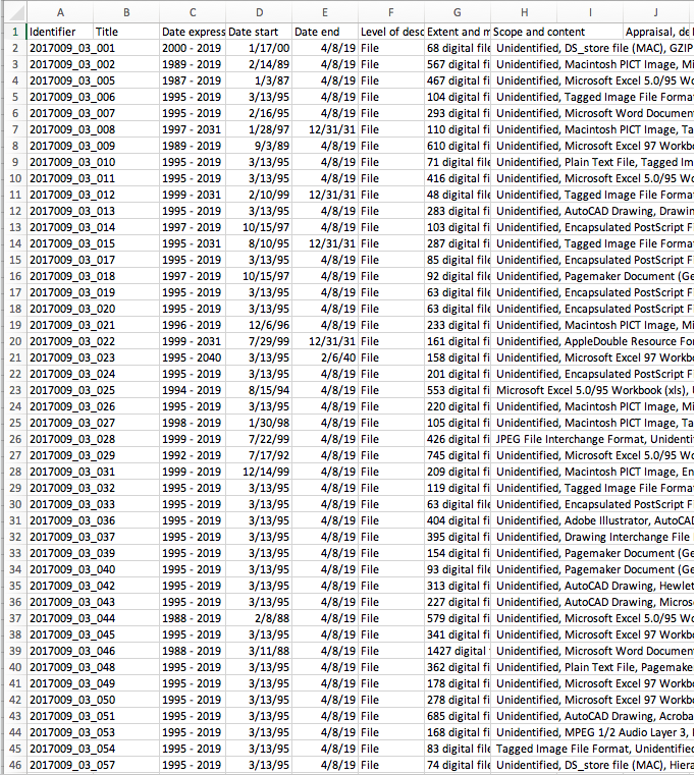

Working closely with the UT Libraries Digital Stewardship department, I created a workflow whereby I extracted files using FTK Imager and generated SIPS and a bulk_extractor report using the Canadian Center for Architecture’s Folder Processing Tool in the BitCurator environment. The only impact on the metadata was a change in the “Date Modified” field, which now showed the date the files were extracted and could be amended to reflect the most recent date in the file tree. While this is an unconventional approach to digital preservation, the resulting AIPs and DIPs are better representations of the original disks and will allow us to provide more comprehensive data for future researchers.

After my presentation, I had the opportunity to talk to a digital archivist about this workflow. We discussed how best practice is ultimately not about perfection, but about preserving and providing access to our materials and documenting the process. While somewhat contrasted from the theoretical approaches I’d both learned in class and adapted from online resources, this approach seemed more natural to me. It affirmed both my processing decisions and the opinions I’ve developed about what best practice in the archival community is and should be. This process has shown me how vital the user is to the archive, especially when developing workflows for digital materials.

As I mentioned in my previous post, I love having opportunities to exercise creativity and problem solving in this position. It’s even better when those opportunities lead to breakthroughs that help me grow professionally and enhance the data we provide patrons. I’m excited to see new developments in our born-digital workflow as we get closer to making this collection available to patrons. Check back soon for a (final?) update from me – I hope you’ve enjoyed learning more about the behind-the-scenes work of born-digital archiving.