Over the past several years, a team at UT Libraries has been developing the UTLARCH GeoData project, a prototype for a new kind of geospatial database that can map and link together data derived from various collections at the Alexander Architectural Archives. In this post, I will summarize our work to date.

View the UTLARCH GeoData project on ArcGIS Online

The core project team has consisted of myself, Josh Conrad, a graduate research assistant, along with Katie Pierce Meyer, Michael Shensky, and Jessica Trelogan. We have also relied heavily on the amazing data work from UT Libraries staff and students including Grace Hanson, Irene Lule, Alyssa Anderson, Abigail Norris, Katie Jakovich, Stephanie Tiedeken, Beth Dodd and Nancy Sparrow.

Buildings of Texas

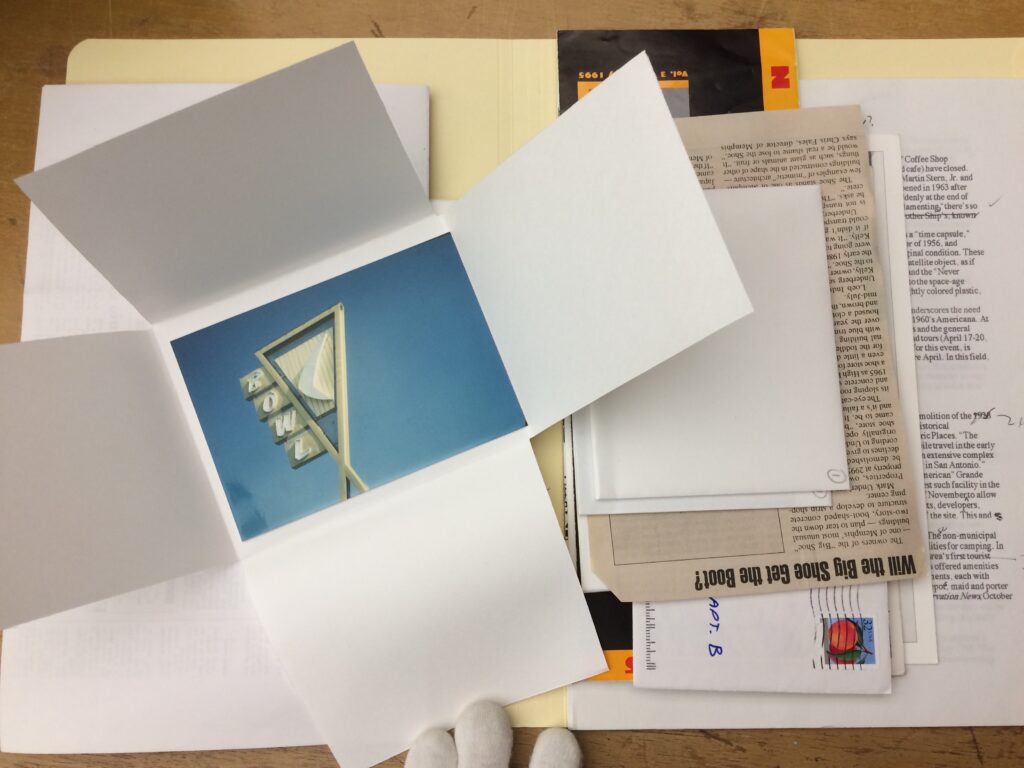

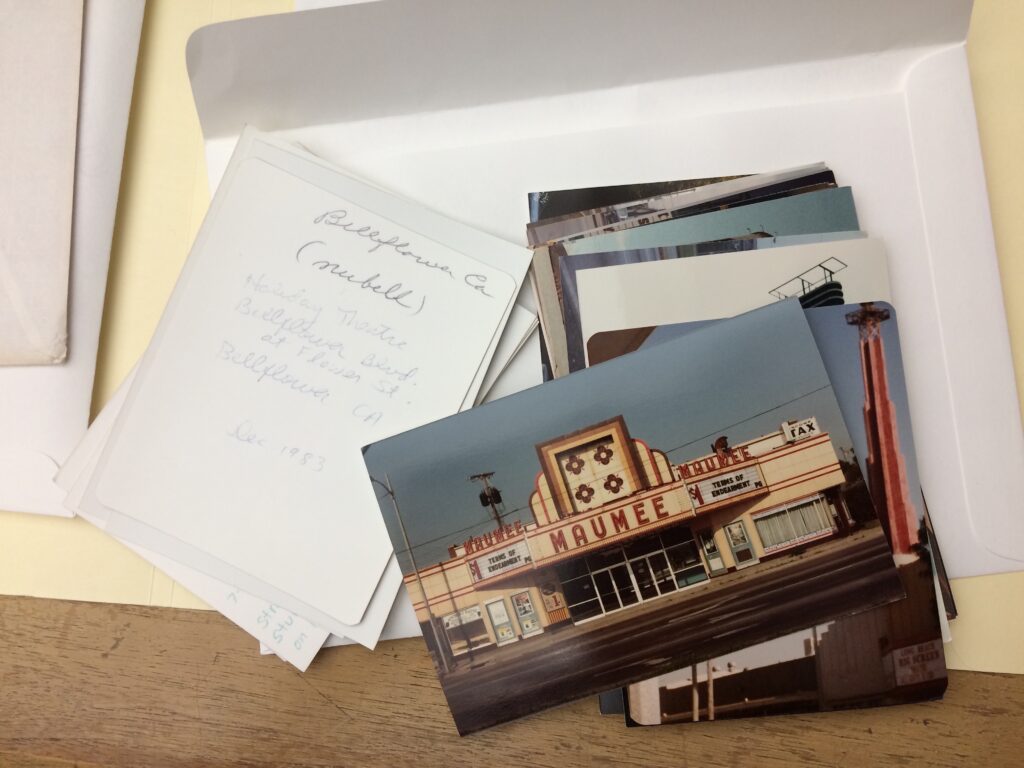

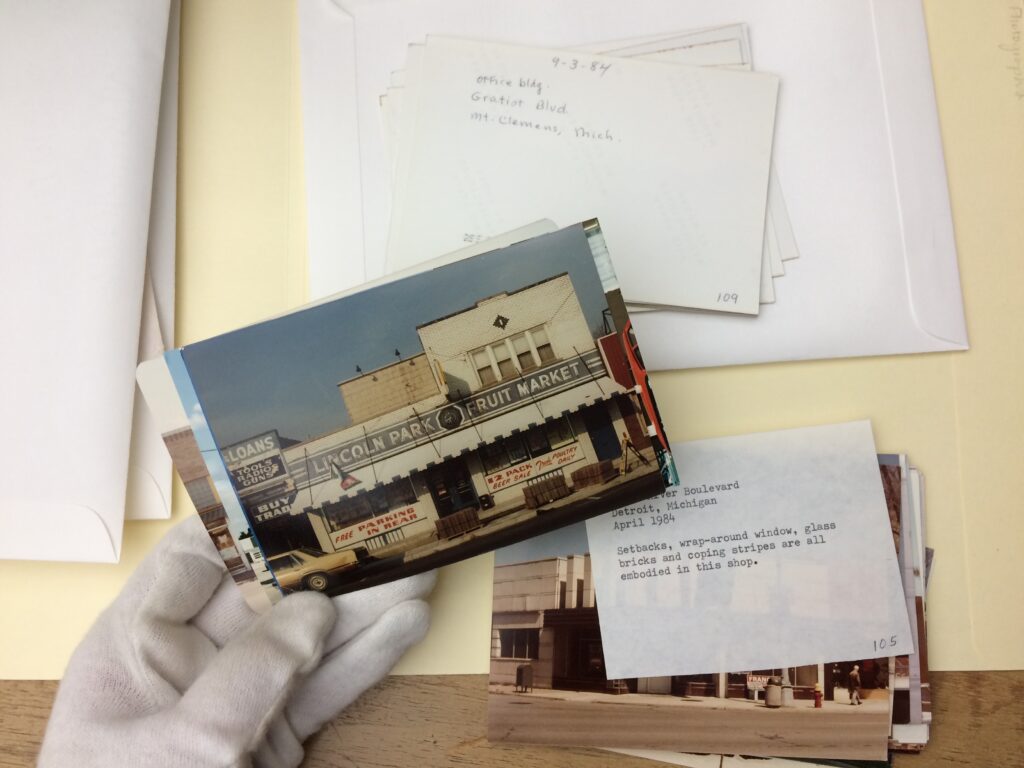

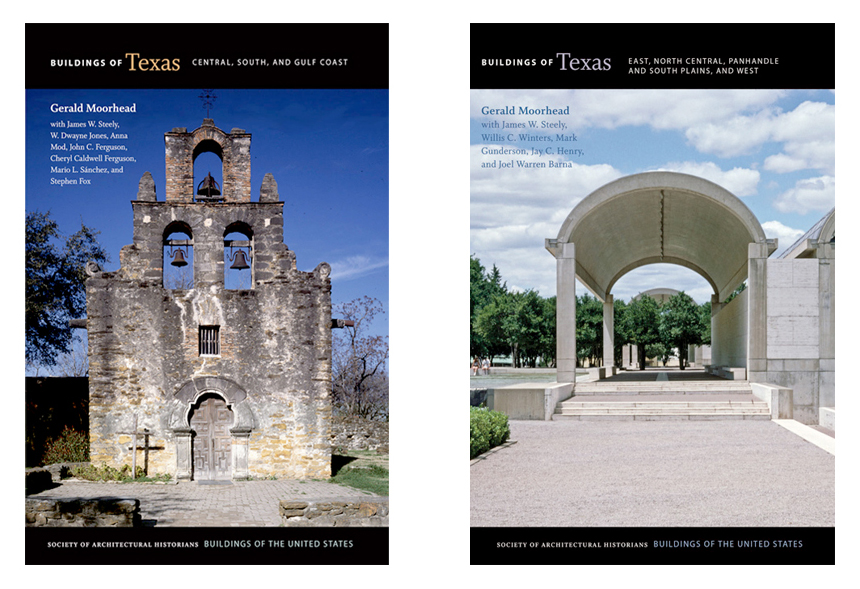

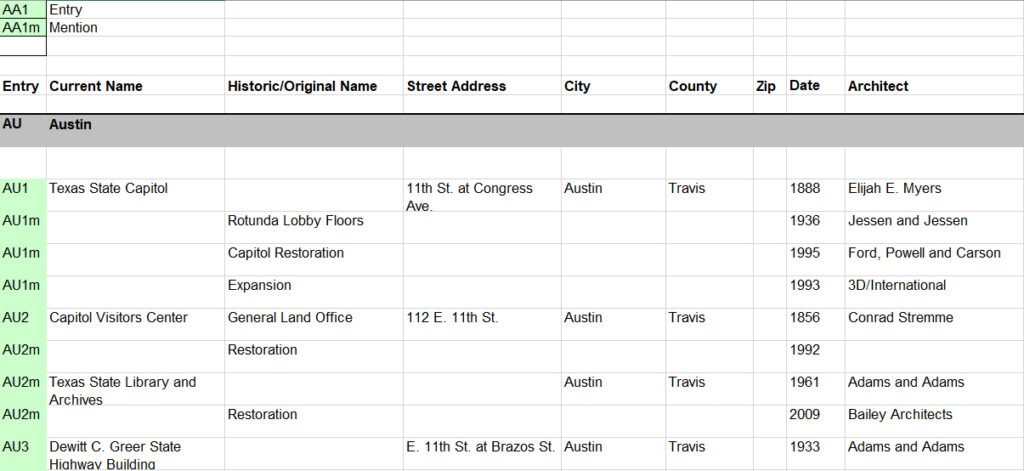

The project began in 2018 after the Alexander Architectural Archives received a new collection donation from architect and historian Gerald Moorhead containing the research and editing material for the two volume book series Buildings of Texas, published in 2013 and 2019. This donation consisted of over 20 boxes of paperwork, 12,000 photographs, and, importantly for our project, a series of eight Excel spreadsheets cataloging over 5,000 places represented in the book series. These spreadsheets included addresses, place names, dates of construction and renovation events, as well as architects and other contributors to these building events.

View the Buildings of Texas Collection finding aid on TARO

View the original Buildings of Texas Excel spreadsheets in the Texas Data Repository

The Buildings of Texas spreadsheets provide a wealth of data about a wide range of architectural projects throughout the state, including many projects represented in other AAA collections. The AAA projects database and finding aids also store a lot of information about the various architectural projects represented in the collections, but many gaps exist in AAA data, especially geographic information such as addresses and coordinates which were not included on donated items such as drawing sets. With the acquisition of the Buildings of Texas datasets, the intriguing possibility arose of filling in these gaps by linking Buildings of Texas data to existing AAA projects data.

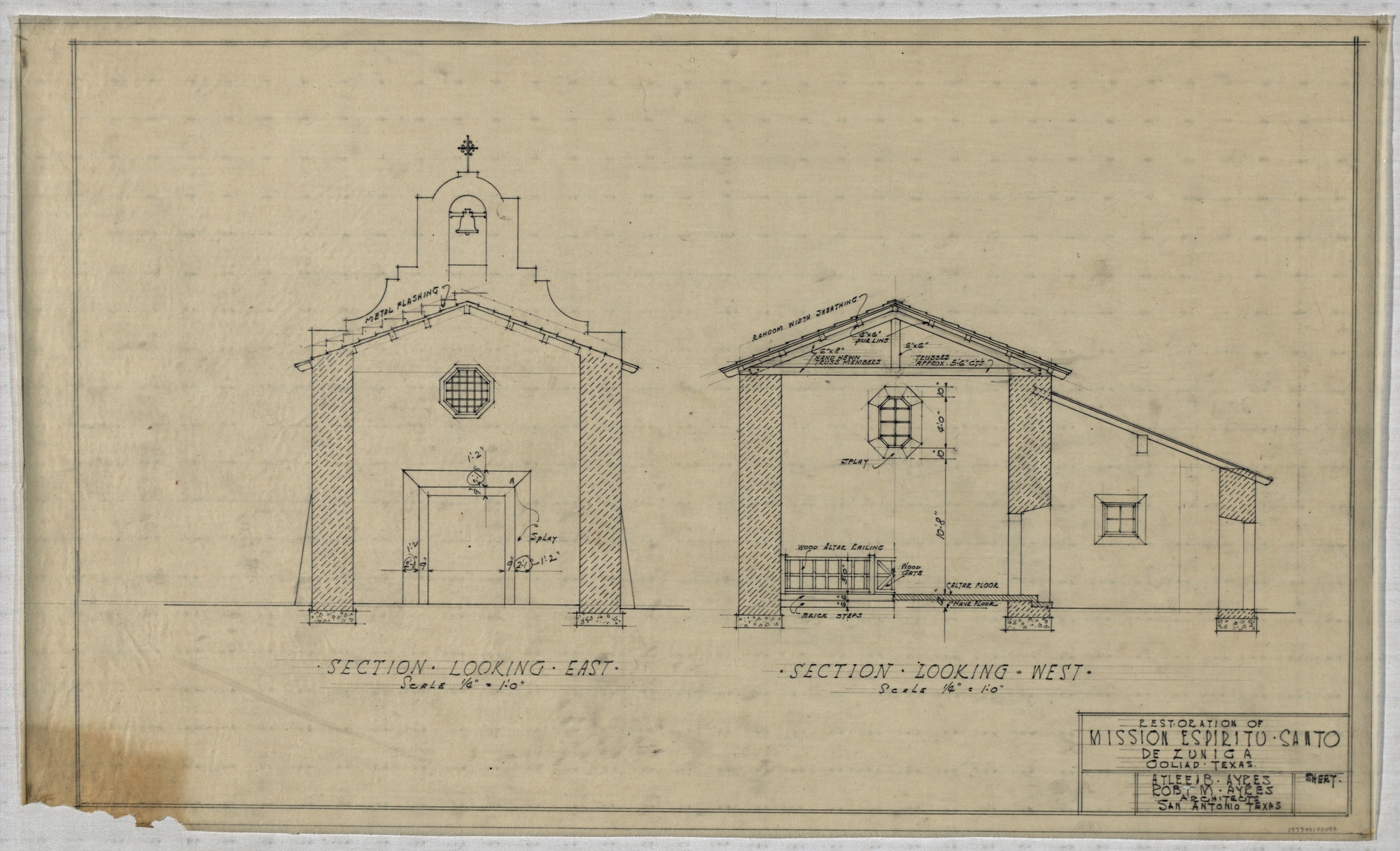

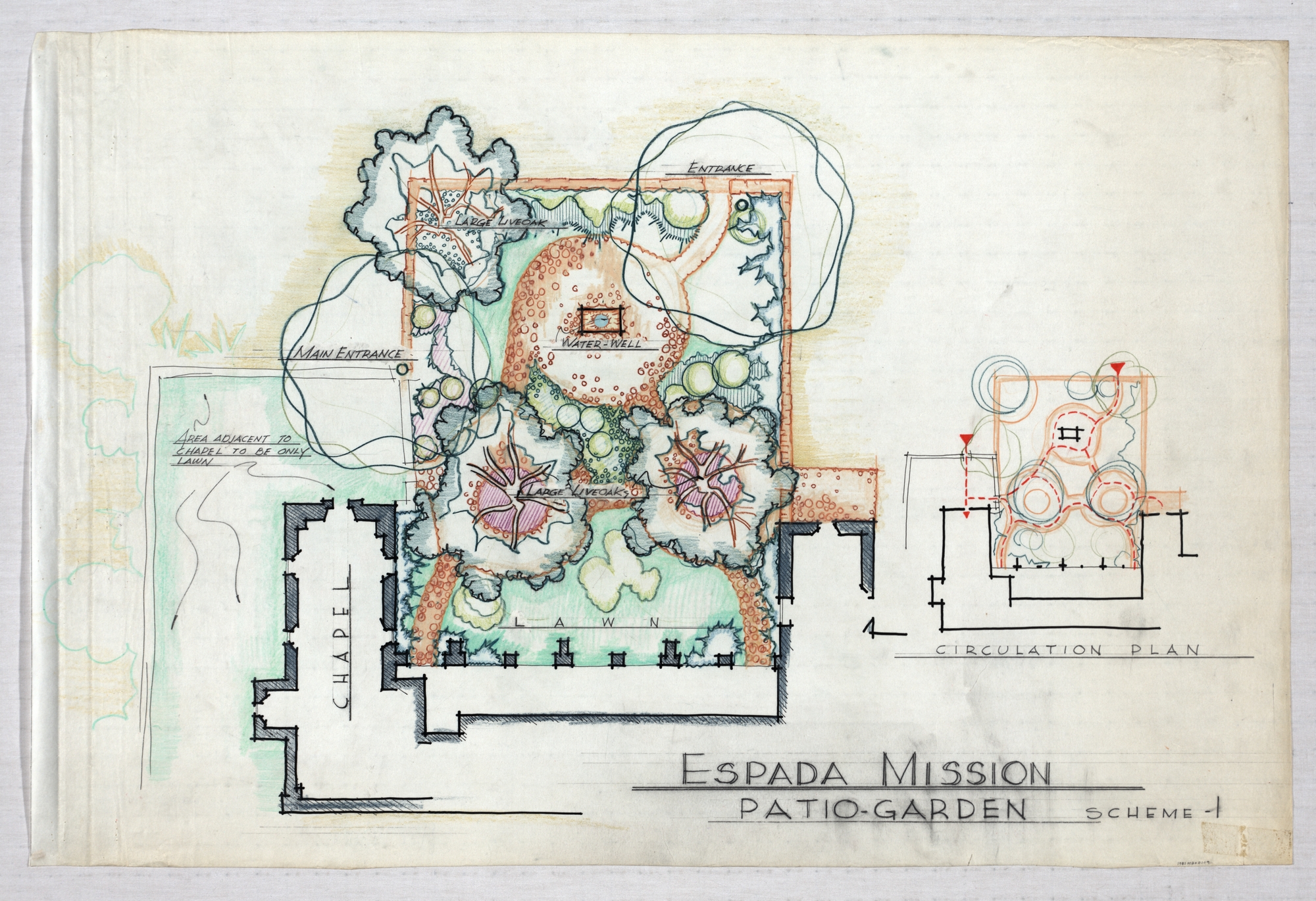

From this seed of an idea, the project concept expanded: why not connect geodata from other AAA collections as well, such as the recently digitized David Williams photography collection and Atlantic Terra Cotta Company photography collection, both now hosted on the UT Libraries Collections portal. Numerous other un-digitized architectural datasets also exist in AAA collections which in the future may be able to be included in this growing linked database, such as the Texas Architectural Survey collection and the historical surveys conducted by architects and historians such as Eugene George and Wayne Bell. Could we include data from outside of the AAA as well?

Linked data model

These early brainstorms coalesced around a plan for new kind of geospatial database that could store and display place data from various linked datasets together on a map. We saw this concept as akin to pre-digital geographic indices such as atlases and gazetteers. We also envisioned this database as a kind of spatial finding aid that researchers could use to find all the items about a place such as photographs and drawings that may be held in multiple collections. Further, if this potential geodatabase will be digital, we could use it to develop map-based digital exhibitions and other kinds of library discovery tools.

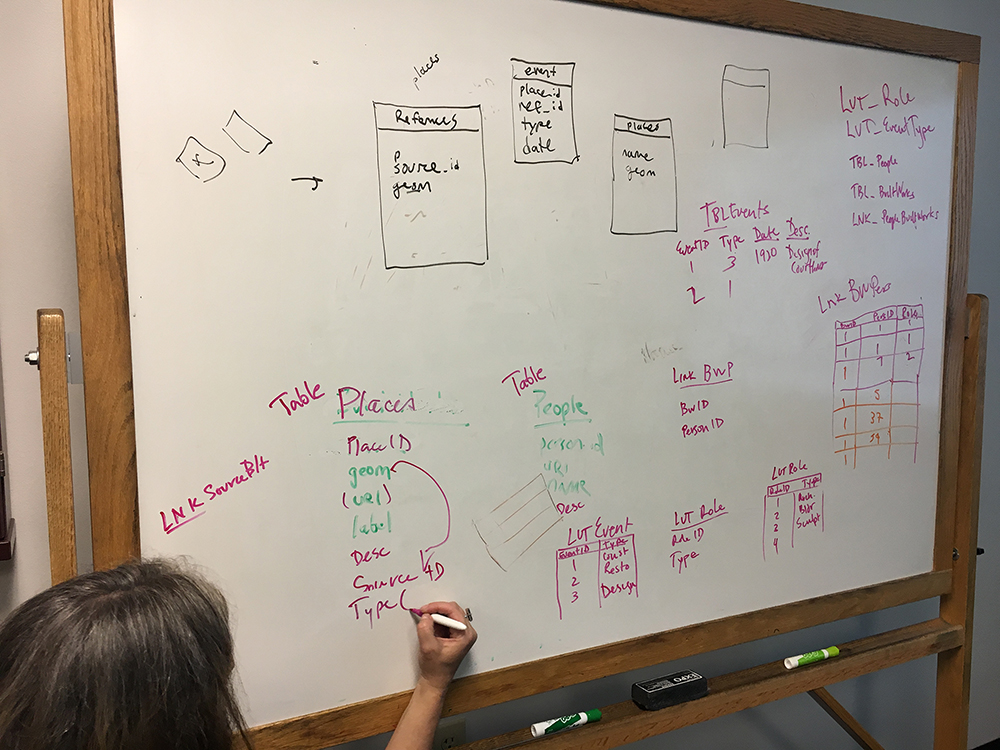

We explored a variety of database models for representing this diversity of data. A single data table would not be sufficient. Places represented in AAA collections are complex and involve multitudes of contributing individuals. Our data model would need to be flexible and allow one-to-many relationships throughout. In architectural data, places are often associated with a number of specific events in time such as dates of construction and renovation. Further, each event is often associated with multiple different people and companies such as clients, architects, builders, and other contributors. And, to add further complexity, events are documented by multiple different artifacts, such as photographs and drawings. We wanted to develop a spatial database that could link people and artifacts to places while also being able to store temporal data that could contextualize them within the history of that place.

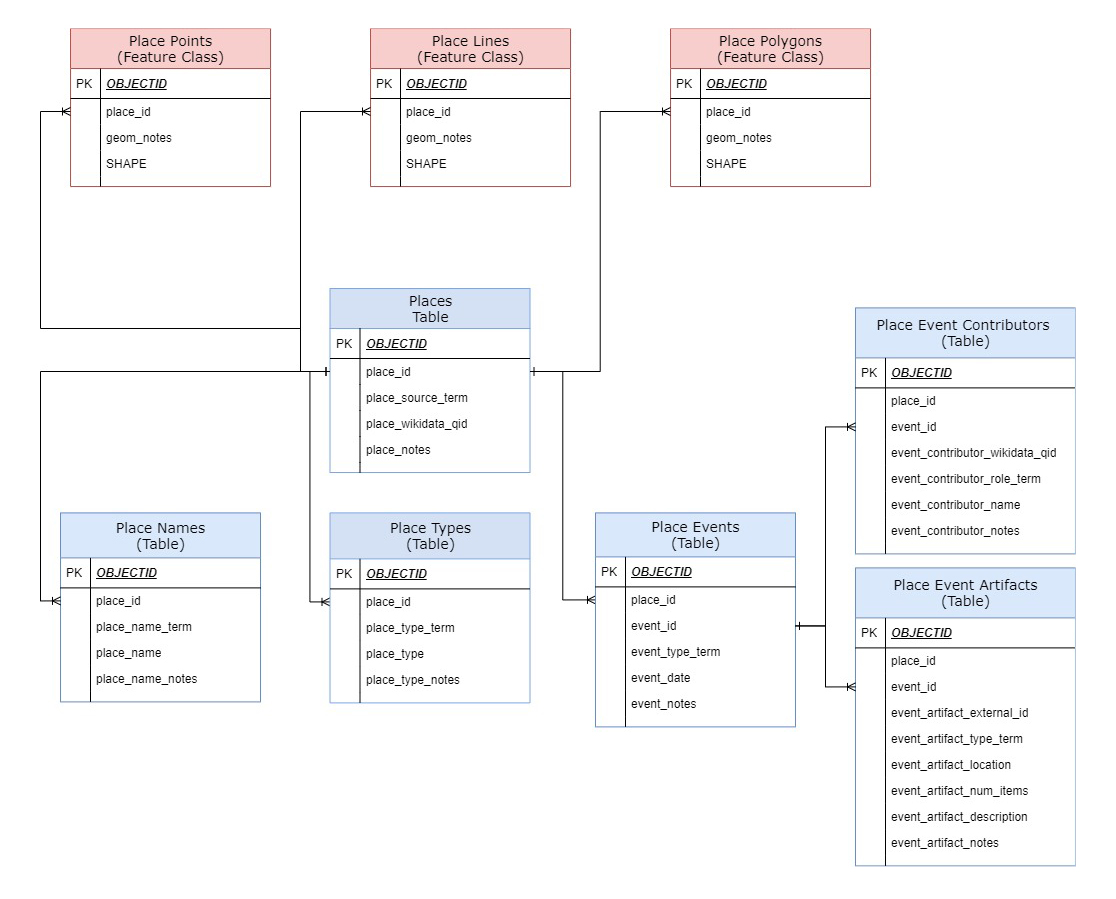

Below is the Entity Relationship Diagram (ERD) of our prototype data model. Centrally, the core table is the Places table. Places represented in this table are labeled with the name of the collection from which the data originates (place_source_term). In order to map the data with a geographic information system (GIS), we connect each place to its geographic representation, a point, line or polygon located somewhere on earth. The three tables at the top (in red) are the spatial tables, or “feature classes” in GIS lingo, that are required by the GIS. One feature class represents points, one represents lines and one can represent polygons. Place data is often represented with a point, essentially a map pin located on or near the place’s location on earth, but places can also be represented with lines, in the case of roads or trails, or polygons in the case of building outlines, land parcel boundaries, and neighborhood boundaries.

The core places table is then connected in a one-to-many relationship to various attribute tables (in blue) that can store multiple values per place. In the Place Names table, places can have many names, such as current and historic names as well as addresses. In the Place Type table, places can have many different types or uses, such as residences, commercial buildings, public buildings, and landscapes such as parks and neighborhoods. Further, places can be sites of multiple events over time, including but not limited to construction and renovation events, documentation events such as the photographing and drawing of that place, and cultural events such as celebrations and commemorations. Thus, the Events table, as our model’s temporal table, stores the dates and event data associated with each place. From the Events table are connected two more attribute tables: the Contributors table, which stores names of people and companies associated with each event; and the Artifacts table, which stores the data about collection items associated with each event.

Within this spatial and temporal data model, multiple data sources can be combined. However, if two or more sources represent the same place, that place will be represented by multiple unconnected records in the places table, one record for each source. Ultimately we want to be able to match these records so that researchers can view all the data available about each place. Preliminary ideas from our team included the idea of creating a “Unique Places” table where matching places could link to a single shared place record, essentially an authority record that could store a standardized geographic representation for that place. We would also want to create an authoritative “Unique Contributors” table.

The prospect of creating our own authority files brought up the question of how we might work with, or contribute to, existing authority file databases such as Getty Vocabularies, who manages two authority ontologies relevant to us, the Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT) and the Union List of Artist Names (ULAN). Further, as a means to broaden representation and allow for multivocality and multiplicity, we felt that we should also contribute our authority records to the linked open data community via Wikidata.

Wikidata

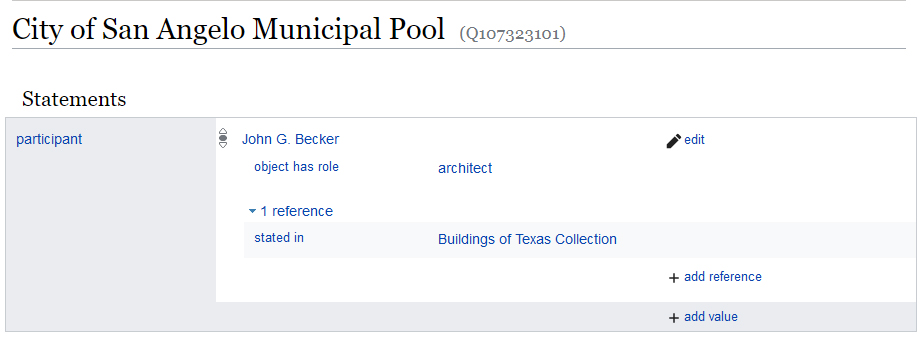

I usually think of Wikidata as the database version of Wikipedia. Similarly to Wikipedia, Wikidata is an open collaboratively-edited platform developed by the Wikimedia Foundation using the CC0 public domain license. But whereas Wikipedia is composed of records of various entities and concepts written in an encyclopediatic narrative prose, Wikidata represents unique entities as structured database records with a data model that they call a “knowledge graph”. A graph data model, which I have also heard called a linked data model, a network model, an ontology model, or an object-oriented model, is an alternative data model used by encyclopediatic knowledge databases and newer authority file systems such as Getty Vocabularies, the Library of Congress Linked Data Service, the Virtual International Authority File, the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model, and Wikidata. In a graph model, data is stored, not in fixed table rows like in traditional relational databases, but rather as a series of “triples” composed of two objects (or “nodes”) and their relationship (or “edge”), and stored in a specialized databases called triplestores. In this more-flexible structure, each unique object can have many different relationships with many other objects. In Wikidata, item records are able to have many different attributes which are each linked to other unique items. The result is a flexible hyperlinked database. The image below shows an example of a Wikidata record containing an attribute that is in turn linked to another Wikidata record, forming a network.

Because Getty Vocabularies and Wikidata both use a linked data model, we are able to match and link records from our different data sources by connecting, or “reconciling”, each record to its authoritative Getty or Wikidata record. However, because Wikidata offers an open-source collaboratively-edited platform, if a Wikidata record for a place or contributor does not exist, we can simply create it on the fly using the Wikidata reconciliation API and Open Refine. This important feature distinguishes it from Getty Vocabularies which is not a publicly editable database (though they do accept new data through partnerships with libraries). Because it allows us to directly manage records, Wikidata can essentially become integrated into our data infrastructure and workflow. In other words, Wikidata can simply become our authority file. In this configuration, our data model is greatly simplified. As shown the ERD above, instead of creating new “unique” tables, the Places and Contributors tables both contain attributes labelled wikidata_qid in which we simply store the Wikidata identifiers (QIDs) that represent each authority record.

Database infrastructure

Because our ultimate goal is to create a geospatial database, we required a GIS database infrastructure. A critical component of this project, one which really made everything possible, was our ability to use the ArcGIS geodatabase and server that UT Libraries ITS has recently installed to support the creation of the Texas GeoData Portal. UTL ITS has been providing the libraries with an incredible data infrastructure from which to build new innovative kinds of discovery, access and digital preservation tools. We are also forever grateful to UT Libraries GIS experts Michael Shensky and Jessica Trelogan for being a part of our core team and teaching us how to navigate the complex matrix of settings and workflows required to host data within this infrastructure.

The GIS infrastructure is essentially composed of three components: a ArcGIS enterprise geodatabase built with Microsoft SQL Server, the ArcGIS Server, and ArcGIS Online. Data tables created on the SQL server are linked to a GIS feature service which can be then added to an ArcGIS Online web map as a set of GIS feature class and tables. Any updates made over time to the core data tables are then automatically updated in the web map.

In order to populate and update the geodatabase over time, our team established a documented data processing workflow that extracts the original data source, transforms it into our linked data model (including reconciling with Wikidata), and loads it into our database infrastructure. This Extract-Transform-Load workflow involves the combined use of the data processing tool Open Refine as well as ArcGIS Pro and can be applied to new datasets in the future.

Results

To date, we have uploaded three datasets into the new geodatabase: the Buildings of Texas Collection, as well as two datasets exported from the AAA projects database representing the Karl Kamrath Collection and the Volz & Associates, Inc. Collection. As part of this process, we have created nearly 7,000 new Wikidata records representing both people and places.

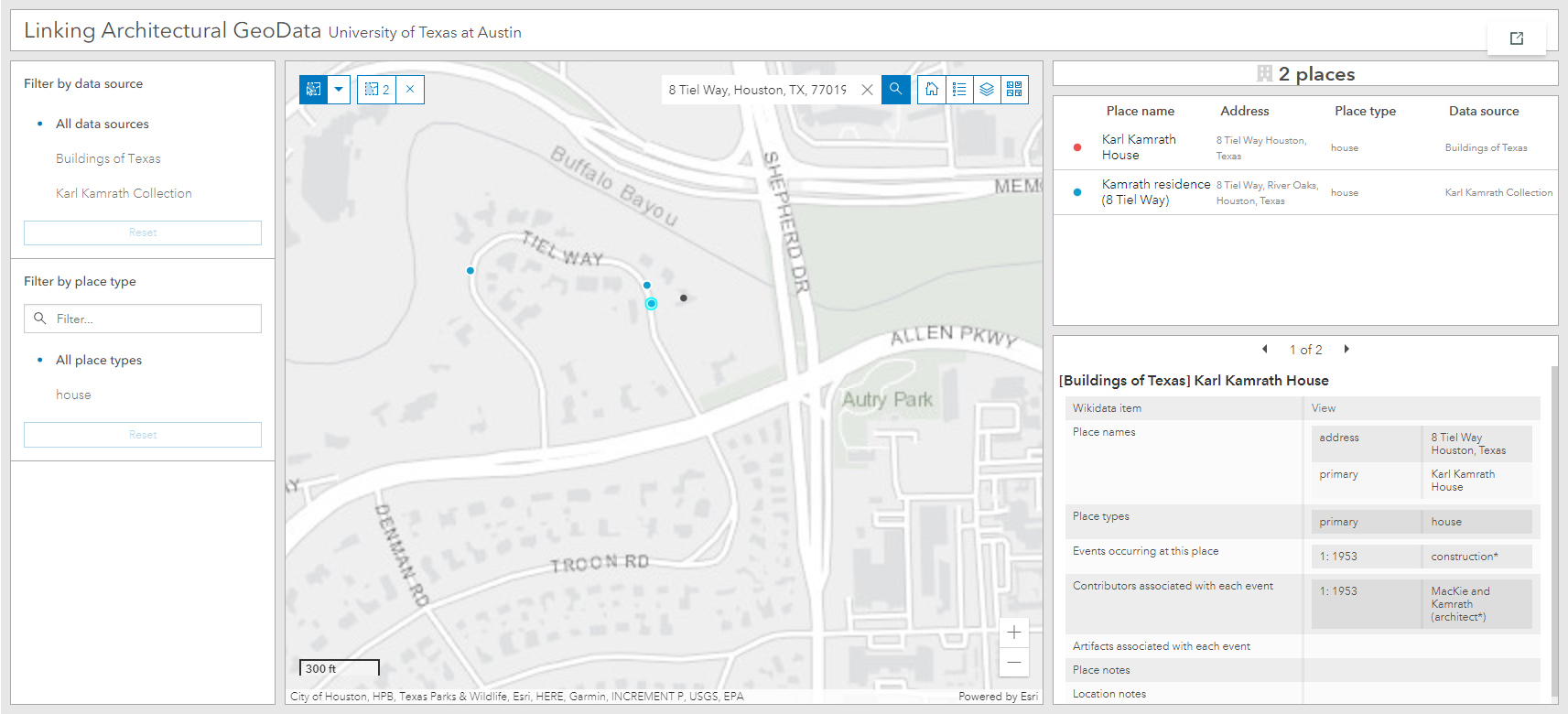

Below is a screenshot of our ArcGIS Online web map and interactive data dashboard. The image shows an example of a house represented in two separate datasets, linked spatially by having the same point coordinates as stored in Wikidata. This house, located at 8 Tiel Way in Houston, was designed by Karl Kamrath. The Kamrath dataset provides data about the drawings he produced for the project which we represent in the geodatabase as “drawing” events using the date at which the house was drawn (as recorded on the drawings). The Buildings of Texas dataset includes data about the home’s construction, which we represent as a separate “construction” event. Together the two events begin to provide a more temporal depiction of this place than each dataset does alone.

The two datasets from the AAA projects database provided us with a workflow template for adding other AAA projects datasets in the future. Digitized datasets extracted from UT Libraries Collections portal metadata are next. Over time we hope to continue refining and filling in the gaps in each of these data sources by developing new editing workflows using the interactive tools in ArcGIS Online. As both the Wikidata and ArcGIS platforms improve over time, we hope to find new ways to link the two more intimately. Currently, for example, ArcGIS Online is not able to asynchronously query external APIs such as Wikidata, so we must continue to store authority data locally. ArcGIS developers has also started integrating graph data models into their products which may allow us to migrate from our relational data model and more-fully embrace linked data practices.

We are excited to be a part of these developing technologies and hope to continue experimenting with new ways of sharing and linking architectural data. Be sure to visit our project dashboard as well as our project StoryMap which explores how linked architectural data can be useful for new research.