Our Washington: A Comprehensive Album of the Nation’s Capital in Words and Pictures, true to its title, explores how intrinsically interwoven the United States government and Washington, D.C., are. Henry G. Alsberg, Director of the Federal Writers’ Project as part of the New Deal program Works Progress Administration, writes in the preface, “if the national governments were withdrawn from London, Berlin, or Paris, those cities would remain imperceptibly altered…[whereas] if the Federal Government were withdrawn from Washington, there would remain a ghost city on a colossal scale” (pg. 11). Our Washington, published in 1939, is a more compact, condensed version of the Federal Writers’ Project book Washington: City and Capital, featuring many of the same photographs and highlights.

Our Washington: A Comprehensive Album of the Nation’s Capital in Words and Pictures, true to its title, explores how intrinsically interwoven the United States government and Washington, D.C., are. Henry G. Alsberg, Director of the Federal Writers’ Project as part of the New Deal program Works Progress Administration, writes in the preface, “if the national governments were withdrawn from London, Berlin, or Paris, those cities would remain imperceptibly altered…[whereas] if the Federal Government were withdrawn from Washington, there would remain a ghost city on a colossal scale” (pg. 11). Our Washington, published in 1939, is a more compact, condensed version of the Federal Writers’ Project book Washington: City and Capital, featuring many of the same photographs and highlights.

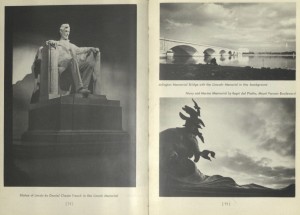

The book begins with a description of Washington’s founding. After the selection of the Potomac as the location for the capital city, Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a French engineer who came to the colonies during the Revolution, was chosen by George Washington to plan the city. L’Enfant  placed the most important buildings on hills, so as to make them prominent and add to the dignity and celebration of democracy. Washington D.C. “was a desolate and dreary place [in 1800 when the government first moved]…but with each emergency in the national life, the Federal City grew and developed” (pg. 14). The following chapter focuses on the Capitol building, the Supreme Court, the Library of Congress, the White House, and other notable buildings, making particular note of the configuration and centralization of the most important institutions of the government in a relatively small area of the city. Much of the rest of the book is comprised of photographs related to other aspects of Washington life including the buildings and areas deemed most important. These photos show embassies, historic homes, festivals, and the landscape of the area.

placed the most important buildings on hills, so as to make them prominent and add to the dignity and celebration of democracy. Washington D.C. “was a desolate and dreary place [in 1800 when the government first moved]…but with each emergency in the national life, the Federal City grew and developed” (pg. 14). The following chapter focuses on the Capitol building, the Supreme Court, the Library of Congress, the White House, and other notable buildings, making particular note of the configuration and centralization of the most important institutions of the government in a relatively small area of the city. Much of the rest of the book is comprised of photographs related to other aspects of Washington life including the buildings and areas deemed most important. These photos show embassies, historic homes, festivals, and the landscape of the area.

Almost of equal interest to this detailed description and historical exploration of the U.S. capital city is the context in which the book was written. The Federal Writers’ Project was one arm of the Works Progress Administration, the most ambitious program laid out by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The WPA, as it was widely known, funded projects in numerous fields, with the ultimate goal of providing jobs and income to as many Americans as possible, including artists and writers. Many of the projects served as a sort of propaganda – the final product celebrated the United States, the government, or encouraged citizens to stimulate the economy by spending newly earned money. Our  Washington is one such project. As a history of the nation’s capital, the book exudes pride in the United States, glorifying the capital city as a global symbol of democracy, strength, and beauty with an extreme romanticization of its history.

Washington is one such project. As a history of the nation’s capital, the book exudes pride in the United States, glorifying the capital city as a global symbol of democracy, strength, and beauty with an extreme romanticization of its history.

Our Washington overall is an informative and interesting, if somewhat biased and propagandistic, history of Washington, D.C.. Featuring photos, sketches, and plans from the city’s past adds to the value of the book as an educational resource. Washington, D.C., the federal government, and the nation as a whole are idealized in Our Washington. Alsberg writes at the beginning that “Washington is…unique in the place it holds in the hearts of all Americans…they come with pride and awe to see their Mount Vernon, their Arlington Cemetery, their Washington and Lincoln Memorials, their government buildings, their Library of Congress, their Capitol” (pg. 11). In spite of the biased nature of the book, this point proves particularly poignant. The United States Constitution begins with the words, “We the People.” The beauty of democracy is, to quote from President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, that it is a “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” Such a grand notion deserves a grand city to represent these ideals. The shining white buildings present the illusion of a perfect city on a hill, and though it is only an illusion of perfection, it is important to remember that these buildings in Washington, D.C., from the Capitol to the White House, are of the people, by the people, for the people. They symbolize the most revolutionary, wonderful part of democracy as a form of government, the foundation that makes the United States a great nation, and something so integral that it makes up the first three words of our Constitution: We the People.

Simon and his co-editors explore the architecture related to the judicial system and the connection between justice and architecture to “examine the effects that architecture has on both the place of justice and on individual and collective experiences of judicial processes” (pg. 1). The book is organized to transition from individual, intimate stories, to more broad commentary.

Simon and his co-editors explore the architecture related to the judicial system and the connection between justice and architecture to “examine the effects that architecture has on both the place of justice and on individual and collective experiences of judicial processes” (pg. 1). The book is organized to transition from individual, intimate stories, to more broad commentary.

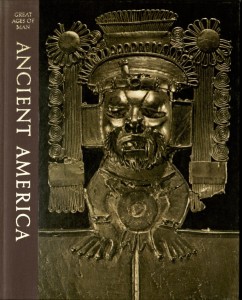

unique in its time. Ancient America was published in 1967, when the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution was still felt, paranoia about the spread of Communism was at an all-time high, and the superior attitude of the United States’ “Good Neighbor Policy” remained strong. This era was a time when the field of history began to shift from being completely Eurocentric to thinking globally. Leonard himself was a longtime correspondent on South American events for TIME Magazine, and even married a Peruvian woman, giving him greater appreciation and admiration for South America than that of many Americans at the time.

unique in its time. Ancient America was published in 1967, when the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution was still felt, paranoia about the spread of Communism was at an all-time high, and the superior attitude of the United States’ “Good Neighbor Policy” remained strong. This era was a time when the field of history began to shift from being completely Eurocentric to thinking globally. Leonard himself was a longtime correspondent on South American events for TIME Magazine, and even married a Peruvian woman, giving him greater appreciation and admiration for South America than that of many Americans at the time.