Viollet-le-Duc and Michel Jordy. The City of Carcassonne and A Visitor’s Guide. Paris: Albert Morancé, [n.d.]. Jean-Pierre Panouillé et al. The City of Carcassonne. [Paris]: Caisse nationale des monuments historiques et des sites, Ministère de la culture, c1984.

Today I broke into new call number territory in Special Collections: Medieval France. I discovered a small guide book to Carcassonne, which is on the list of places that I have not visited but would like to do so. It thus struck a cord. I was surprised to discover that the book had been written by Viollet-le-Duc. I had not realized that he had led the restoration of the fortification. UNESCO highlights Viollet-le-Duc’s importance as culturally significant to the monument: In its present form it is an outstanding example of a medieval fortified town, with its massive defences encircling the castle and the surrounding buildings, its streets and its fine Gothic cathedral. Carcassonne is also of exceptional importance because of the lengthy restoration campaign undertaken by Viollet-le-Duc, one of the founders of the modern science of conservation (UNESCO, “Historic Fortified City of Carcassonne, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/345/, accessed July 31, 2014).

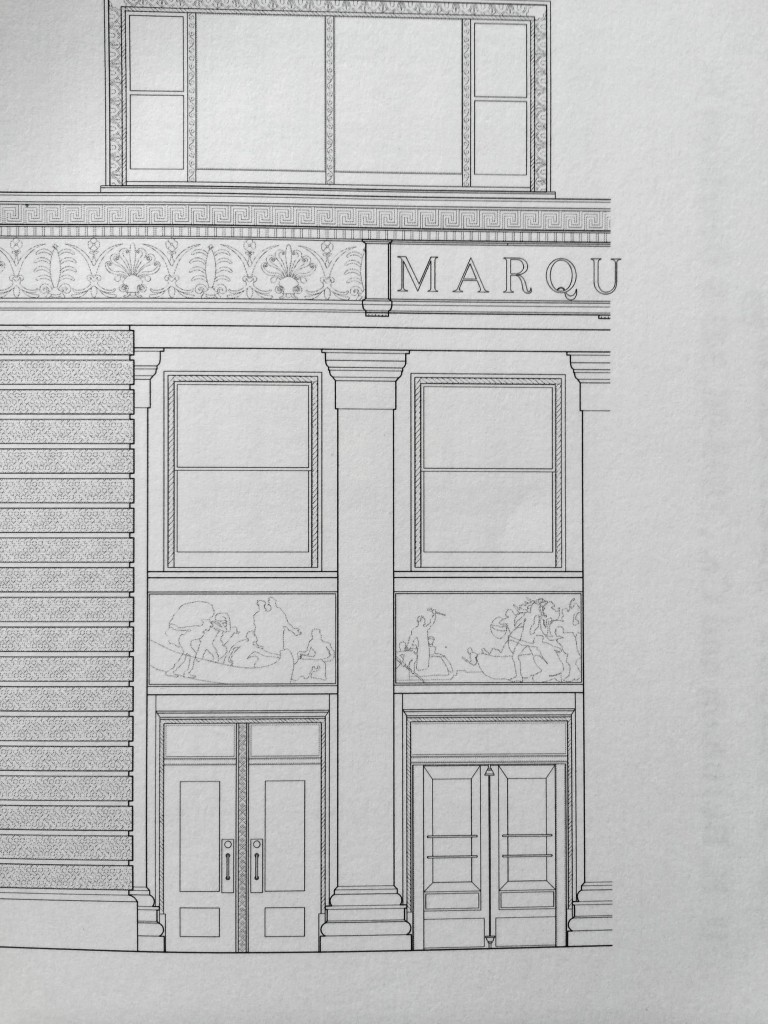

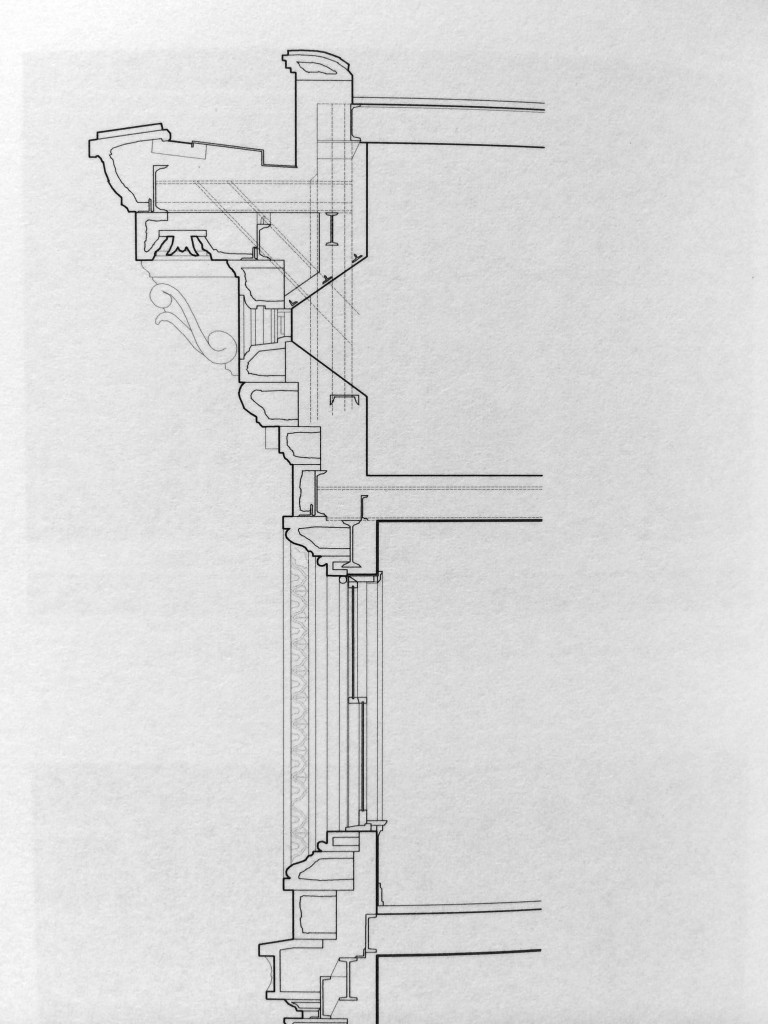

Viollet-le-Duc wrote the historical narrative of the site. His account is very much that of a military history as it relates to construction and destruction. Michel Jordy provides a brief description of the major architectural features of Carcassonne– the towers, the gates, the castle, and church. Jordy writes in the conclusion: This summary description of the City of Carcassonne may perhaps bring out the value of these remains, their interest and importance from preserving them from decay. I doubt whether there be elsewhere in Europe as complete and formidable an ensemble of 6th, 12th and 13th century defensive works, a more interesting subject of study, a situation more picturesque (pg. 29). While I was disappointed that Viollet-le-Duc did not discuss the restoration process, I understand that the authors’ purpose was rather to impress upon the visitors the historical and architectural significance of the site itself.

The library also posses in the lending collection a more recent guide book of Carcassonne, The City of Carcassonne, with more detailed information including a brief overview of the restoration and diagrams of the evolution of the site from the sixth century B.C. through the thirteenth century. Both UNESCO and Stephen Murray’s Mapping Gothic France have more extensive images of the site.