Hello! This is Irene Lule, Graduate Research Assistant for the Alexander Architectural Archives (AAA), with information about our most recent processed collection, the Society for Commercial Archeology (SCA) records. Formed in 1977, the Society for Commercial Archeology is a nonprofit organization focused on the 20th century built environment. Its collection at the Alexander Architectural Archive documents the activities and business of the organization from its inception to the present. From diners to neon signs, SCA publishes a quarterly newsletter, Road Notes, and a journal, SCA Journal along with organizing tours and conferences for its members. The value of any collection is always dependent on the user. For myself, the processor, learning more about processing archival collections, how an organization functions, and a look into commercialism from the mid-20th century are three of the most important. The following blog post will discuss some of the challenges and highlight some of the true gems in the collection.

Challenges

The overall goal of any processing project is to establish physical and intellectual control over a collection. Measuring at 9.42 linear feet and with over 900 photographic materials, the SCA collection can be called an artificial collection, which is “a collection of materials with different provenance assembled and organized to facilitate its management or use.”[1] During the first two accessions (the act of acquiring/transferring archival materials to a repository) in 2016 and 2017, a vast majority of the material came from former SCA board members including the Alexander Architectural Archive’s curator, Beth Dodd. Combing the records of different board members to create one cohesive collection is a difficult task mostly because everyone has a different way of organizing their individual records. The way one person files their documents will not be the same as the next person. In this case, we attributed many of the folders to their original creator. For example, Beth Dodd was one of the co-organizers of the SCA’s conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico in September 2008. Since many of the records contain her personal notes, we made sure to attribute the proper folders to her. Bringing together the records of former board members is critical in creating the SCA collection, but it is also important to attribute the individual creators when appropriate.

Other challenges with the collection include privacy and photographic materials. Since many of the records are from a single individual, names, addresses, emails, and phone numbers are found throughout. As archivists, we have a code of ethics which speaks directly to protecting the privacy of the individuals in a collection. For SCA, each folder with personal information was labeled as “Restricted” This label serves as a warning to Nancy Sparrow, who is in charge of public services for the Alexander Architectural Archives. To be clear, the “Restricted” label does not necessarily mean the material will not be available for research. The label notifies Nancy to go through the material and determine the best course of action including redaction of sensitive information. Redaction is “the process of editing text for publication.” All of these measures are used to ensure the privacy of the individuals featured in the collection.

Photographic material in any collection is always challenging due to its specialized housing needs. In the case of SCA, a portion of photographic material was found in envelopes. As archivists, we have to determine the best way to rehouse these items while also maintaining the original order and provenance. In many cases, I rehoused the photograph in a four-flap enclosure and attached the original letter using a plastic paper clip, which is much less harmful than metal paper clips since metal may rust and stain. This tells others that these items are meant to be together. I also included a small note on the top of the enclosure indicating where the photograph came from as a secondary measure.

Collection Highlights

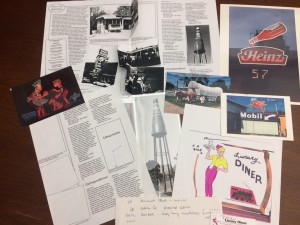

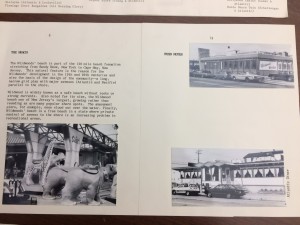

One of my personal favorite features of the SCA collection is the material documenting the publication of the quarterly newsletter, SCA News (now known as Road Notes) from 1994-1999. We were fortunate to acquire the records of its former editor Gregory Smith. As editor, Greg received correspondence, letters, and clippings from SCA members and the general public about the current events in the commercial built environment. A vast majority of our photographic material comes from this section of the collection including some wonderful photographs of neon signs.

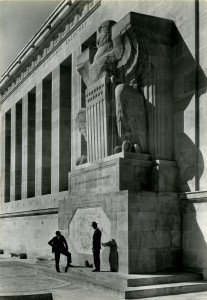

Additionally, the SCA collection documents the various events of the organization. Particularly active in the 1980s, tours and conferences featuring diners to quirky cities like Wildwood, New Jersey provide a glimpse into the past activities of the organization. These events served the purpose of bringing together individuals with shared interests.

Along with these two features, SCA also contains the minutes, agendas, and various administrative records of the organization. Given its status as an artificial collection, there are some gaps we are hoping to fill through outreach. We recently attended the SCA’s 40th anniversary conference in Cincinnati, Ohio where we presented on the project and also sought archival material donations. We are expecting to receive future accruals. I often think of the SCA collection as a living collection. After I leave the Alexander Architectural Archives, someone else will continue to work on integrating both legacy and current materials into the collection. As long as SCA exists, this collection will continue to grow.

Personal Notes

The Society for Commercial Archeology collection has a very special place in my career. As the largest and most complex collection I have ever processed, I have taken away a lot of lessons about rehousing, description, arrangement, and project management along with educating me about a quirky and unique part of the built environment. I am grateful to Stephanie, Beth, and Nancy for this wonderful opportunity. Please feel free to schedule an appointment with Nancy Sparrow if you wish to view the SCA collection. We are currently wrapping up the final edits of the SCA finding aid, which will be made available on Texas Archival Resources Online and ArchiveGrid.

References

[1] “Artificial Collection,” Society of American Archivists, accessed November 20, 2017.