Gordon Home’s The Romance of London highlights “how many of these architectural links with the centuries long past still exist in London” in hopes of encouraging citizens to care about the futures of these historic places (pg. 2). Published in 1910, The Romance of London includes illustrations of the iconic buildings around London and seeks to tell the story of the city through these buildings.

Gordon Home’s The Romance of London highlights “how many of these architectural links with the centuries long past still exist in London” in hopes of encouraging citizens to care about the futures of these historic places (pg. 2). Published in 1910, The Romance of London includes illustrations of the iconic buildings around London and seeks to tell the story of the city through these buildings.

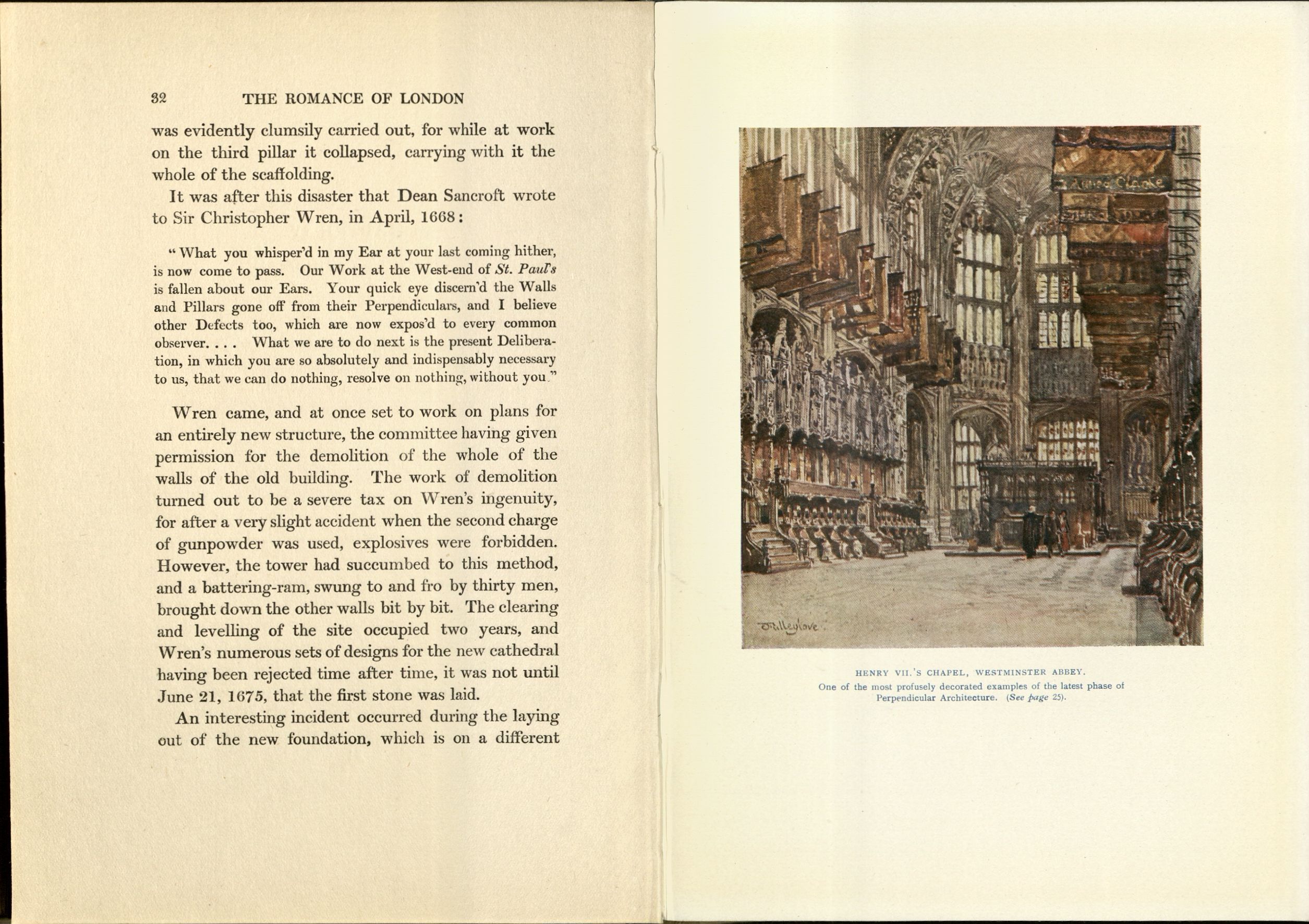

Home explores early London (namely as it was under the Romans and the Saxons), the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey, St. Paul’s Cathedral, The Guildhall, and other landmarks. The chapters on each structure are short histories that help to contextualize the buildings, though Home includes little about their contemporary (in 1910) uses. In the case of the Tower of London, one of the most famous buildings in the city, there is only a brief mention at the end of the chapter of how the building has served many purposes, as a “castle, a royal palace, and a prison, and is now an arsenal and one of the most popular show-places in London” (pg. 17). Home spends a great deal of time exploring London’s churches, including Westminster Abbey (which constitutes the longest chapter in the book), St. Paul’s Cathedral, and the chapter on “Some Old London Churches.” Together, the three emphasize the role of the Church, both the Catholic Church and the Church of England, in London’s history. As the center of politics in England, London was also the seat of power for religious figures in the nation. Home discusses the construction of Westminster, particularly; with its Gothic architecture and long history, Westminster remains the most prominent church in the city, host to the coronation of every monarch since 1066, royal weddings, and other major British events. Where Westminster Abbey is distinctly Gothic, St. Paul’s Cathedral is Roman and Corinthian in style, though the original St. Paul’s (destroyed in the fire of 1666) was also Gothic. The new St. Paul’s contains elements of Gothic and Roman architecture, thereby paying homage to England’s history as a Roman occupied territory and the popularity and frequency of Gothic architecture in England. The golden dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral remains an iconic part of London’s skyline as a representation of a blend of much of England’s past.

When the book was published in 1910, England had just come through a major constitutional crisis, leading to a sudden general election early in the year. There was a desire to restore regular order to the nation, and London most particularly, as the seat of government. After such a tumultuous moment in Britain’s history, it is understandable that Home would wish to look back on the monuments to British greatness in one of the world’s most splendid cities. And yet this ignores the majority of Londoners’ experience. Most of the city’s inhabitants did not enjoy the benefits of London’s palaces, or have the privilege of moving among the most elite of British society who would have been at Westminster Abbey for the coronation of a new monarch. In truth, many of London’s citizens lived a very different life from the world portrayed by Home; there were no castles or royal jewels or grand Elizabethan Halls in their lives. To them, London was teeming with carts and carriages, grime, and suffragette protests, a social context which is ignored in The Romance of London. Much of what Home espouses as London was inaccessible to the average citizen in the city.

The Romance of London portrays only specific parts of the history of the city. Home is true to the title of his book: it is little more than a romanticized history of London and its buildings. London is undoubtedly a romantic city, full of cobblestone streets, stone buildings, and tributes to the grandness of the British. Humans have a tendency to record in history that which is favorable to themselves, often to the detriment of the average person. Those ordinary stories, equally as valuable as those Home tells about Kings and Templars and religious leaders, are hidden or ignored. This is not at all unusual, but nonetheless lamentable. London’s history is partially written in its famous buildings, and though Home briefly mentions the Italian and English workers who built Westminster Abbey, they possess rich stories of their own that are not told. Likely, those stories are lost forever, and the architectural history of these buildings is the poorer for it. For all the wealth of Britain’s social elite and the richness of London’s past, Home’s telling of its history ignores the average Londoner, whose experience of London was not the romantic, idealized version of he portrays.