Gillian Naylor’s 1971 book The Arts and Crafts Movement: A Study of Its Sources, Ideals and Influence on Design Theory explores theory and purposes of the Arts and Crafts movement. According to Naylor, “its motivations were social and moral, and its aesthetic values derived from the conviction that society produces the art and architecture it deserves” (pg. 7). This is, in part, what Naylor seeks to understand. By placing the Arts and Crafts movement in its historical context, as well as demonstrating how the movement fits in the larger field of design.

Gillian Naylor’s 1971 book The Arts and Crafts Movement: A Study of Its Sources, Ideals and Influence on Design Theory explores theory and purposes of the Arts and Crafts movement. According to Naylor, “its motivations were social and moral, and its aesthetic values derived from the conviction that society produces the art and architecture it deserves” (pg. 7). This is, in part, what Naylor seeks to understand. By placing the Arts and Crafts movement in its historical context, as well as demonstrating how the movement fits in the larger field of design.

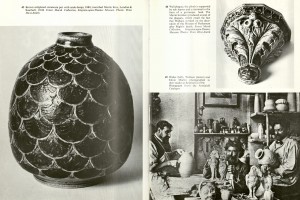

Starting from Britain and moving into other European countries and the United States, the Arts and Crafts movement had a profound influence on design. The movement encouraged the consideration of society in design, as architecture and popular designs are the product of the society in which they are created. Also, one aspect of the movement encouraged the making of products by hand, rather than by machine. This was most particular to Britain, where there “was the conviction that industrialization had brought with the total destruction of ‘purpose, sense and life'” (pg. 8). So the encouragement of handmade products became a major aspect of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Taking the reader through the history of the movement, and even the figures and events which led to the movement, from Pugin and Ruskin to William Morris to the guilds, so that Naylor concurrently provides a history of design. She explores design and the changes in trends through the designs and lives of the major figures who made the Arts and Crafts Movement possible.

In fact, The Arts and Crafts Movement is considered one of the early seminal texts on the history of design. Published in 1971, the book was written in the midst of a challenging time in Naylor’s career, as she sought to shift from writing popular magazine articles to more scholarly endeavors. Naylor became one of the first female writers at Design magazine in 1957, run by the Council for Industrial Design (COID). As such, such was assigned pieces related to “women’s interests.” Through this position and the pieces she wrote for Design, Naylor gained expertise in the field of design and design history. After giving birth to her son (having a child, her contract with Design dictated, meant she had to resign her position), she did some freelance writing for Design, but ultimately focused on writing scholarly works on the history of design and architecture, eventually becoming a professor of the subject. At a time when women were still forced to leave their jobs after becoming mothers, Naylor managed to continue to pursue her passion for design history and become one of the foremost experts on the topic, writing several texts which remain some of the most influential in the field of design, including The Arts and Crafts Movement (Pavitt, Jane. “Gillian Naylor (1931-2014).” Journal of Design History, Volume 27, Issue 2. 2014.).

Arguably, the life of Gillian Naylor was just as fascinating and important as the book she wrote is influential. Not only did she write one of the defining texts of design history, but she also wrote two major books about the Bauhaus (The Bauhaus in 1968 and The Bauhaus Reassessed in 1985). Naylor serves as a reminder of the many challenges and hurdles women faced in building careers as recently as the 1960s. She was relegated to “women’s topics” as a writer at Design and yet went on to become one of the most respected scholars on design history in Britain. A member of a panel which awarded Naylor an honorary doctorate in 1987 noted that, “‘If Sir Nikolaus Pevsner is the father of design history, then Gillian Naylor is its favorite aunt.'” Examining the career of Gillian Naylor, though, it is clear that she is far more than a favorite aunt of design history. As an art historian, especially of architecture, Sir Nikolaus  Pevsner is a critical figure in developing the line of scholarship through which the history of architecture and design is viewed. But, Sir Nikolaus had little to do with design history, specifically; he certainly does not deserve the label of “father.” In truth, Naylor is more the mother of the history of design than anything else, and displayed a true and rare passion for the subject. It would have been easier for her to find another job with a magazine that did not require her to resign once she became a mother, but instead she chose to continue writing about design history. That kind of love for the history of design and perseverance through challenges warrants a far higher honor than the label as the “favorite aunt” would suggest.

Pevsner is a critical figure in developing the line of scholarship through which the history of architecture and design is viewed. But, Sir Nikolaus had little to do with design history, specifically; he certainly does not deserve the label of “father.” In truth, Naylor is more the mother of the history of design than anything else, and displayed a true and rare passion for the subject. It would have been easier for her to find another job with a magazine that did not require her to resign once she became a mother, but instead she chose to continue writing about design history. That kind of love for the history of design and perseverance through challenges warrants a far higher honor than the label as the “favorite aunt” would suggest.