While searching for all of the items in Karl Kamrath’s Collection last semester, I was directly exposed to the vast depth and diversity of a successful architect’s personal library. From Alden Dow to Katherine Morrow to Richard Neutra, Kamrath’s collection spanned decades and encompassed elements of major movements and achievements in the 20th century.

While his collection contains some quintessential readings that were quite prolific (such as Louis Sullivan’s Kindergarten Chats and Other Writings, Hassan Fathy’s Architecture for the Poor: An Experiment in Rural Egypt, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s The Future of Architecture), there are also some limited publications of several design projects that Kamrath and his firm were associated with. As I sifted through special collections to find these professional reports, one caught my eye before I even noticed the Kamrath Collection stamp on the cover: The Monona Basin Project.

My interest directly stems from the report’s subject: a schematic master plan for the city of Madison, Wisconsin. As a University of Wisconsin graduate who spent five years in Madison, I was immediately intrigued by the possibility of being able to compare my visual of Madison with a plan dating back to 1967.

For anyone that’s either been a resident of the greater Wisconsin-Illinois area or happens to be a Frank Lloyd Wright buff, you know that Wright’s career began in Madison as a student at the University of Wisconsin. Though he never completed his engineering degree, he went on to realize many significant projects in Madison and the surrounding area, including the Robert M. Lamp House, Unitarian Meeting House, and Taliesin in nearby Spring Green, one of his most famous projects. However, Monona Terrace likely possesses one of the most interesting timelines of all of Wright’s works – and I’m here to share that story with you all!

Wright originally envisioned a “dream civic center” for the city of Madison as early as 1938. Situated along the shores of Lake Monona – one of Madison’s largest lakes – and within walking distance from the state’s Capitol building, his initial plan called for a rail depot, marina, courthouse, city hall, and auditorium. However, the County Board turned down his proposal with a single vote.

In 1941, approval for a municipal auditorium was passed, and Wright presented a modified version of his Monona Terrace plan to the board yet again. However, instead of another rejection, a different conflict intervened – World War II. That very same inhibitor proved to be a catalyst for Wright’s project after the end of the war, as the economy boomed; Wright was ultimately selected as the architect for the project in 1954. He was quoted as saying his appointment of project architect for the Monona Terrace by the voters of Madison meant more to him than any other award at the time.

In 1959, Wright completed his last rendering for the project. Later that year, he passed away in August – followed by the opening of the iconic Guggenheim Museum in New York City in October. Scholars have noted the striking curvilinear similarities in form and intent between the Guggenheim and Wright’s plans for the Monona Terrace – similarities tat would not be realized until decades later.

In 1966, the site of the Monona Terrace project was revisited, and Taliesin Architects were recruited to develop a master plan for the site and the city. This schematic proposal, which became known as The Monona Basin Project, is outlined in Kamrath’s copy of the same name.

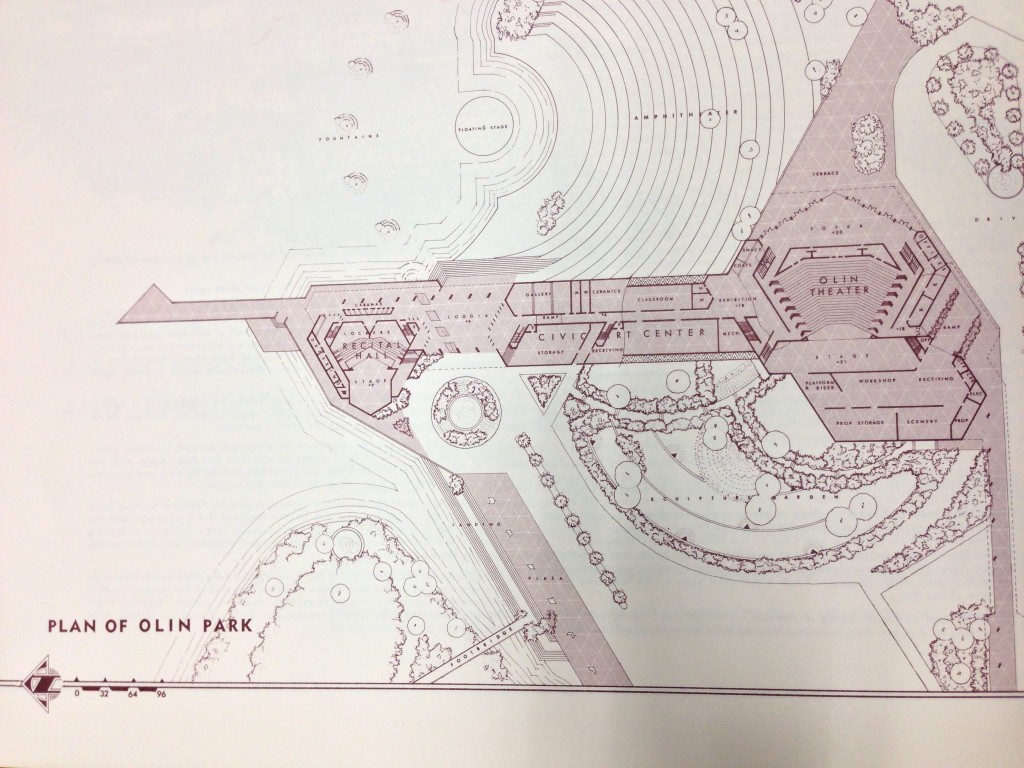

The renderings and drawings within the pages of this proposal are absolutely stunning. Full of both organic and geometric shapes and careful, sinuous line work, the pages seem tinged with the memory of Frank Lloyd Wright.

For those of you that have never visited Madison or studied the Monona Terrace, you may think this is the end of the story, right?

False. This elaborately documented proposal – which included three miles of shoreline; the redevelopment of Olin Park, located across the lake from the Monona Terrace; and the beginning phases of a 2,500-seat performing arts center – was excessively over budget and subsequently halted by the mayor! I know, I know – the rate at which I’m curating this story makes it seem like it was a imaginative project and never completed. But I promise, it’s real.

Throughout the 1980s, several proposals for a new civic center in Madison were submitted by developers – but all of them failed. In the early 1990s, the then-mayor heavily lobbied for the support of reviving Wright’s original 1959 proposal and turning his vision into a reality.

Finally, between 1992-1994, funds were allocated from a number of sources, and the construction on Wright’s civic center began. Its interiors were redesigned by the Taliesen architect Tony Puttnam, and in 1997, the Monona Terrace was opened to the public – 59 years after the original inception of the project and 38 years after Wright’s death.

Today, the Monona Terrace is a hub for cultural events, weddings, professional conferences, and more. As a frequent visitor during my Madison days, I can confirm that Frank Lloyd Wright’s contributions to the project are highly celebrated and integrated into nearly every facet of the user experience; for example, the grand hallway from the main entrance functions almost as a gallery of Wright’s work, lined with photographs of projects spanning his entire lifespan. This posthumously-built icon of a city, full of a tumultuous and contested history, is one of my favorite Wright-influenced works, and gives a glimpse into the incredible complexity behind the ideation and completion of an architectural project.

Searching for all of the books in Karl Kamrath’s collection has proven to be one of my most educational experiences. I have learned more about the cities I love – Madison, Chicago, Austin, and more – and delved into the sources of inspiration of a successful architect. Stay tuned for another blog post on a similar proposal involving Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., also from Kamrath’s collection. These behind-the-scenes stories are so fun to tell!

Interested in exploring the Monona Basin Project in detail? The title discussed above is housed in our Special Collections under the call number -F- NA 9127 M33 T35 1967.