Written to accompany Art in Progress, the Museum of Modern Art’s fifteenth anniversary celebration exhibit, Elizabeth Mock’s 1944 book Built in U.S.A. is a portrait of an institution granting itself a victory lap for it’s role in establishing then-modern tastes. Taking their taste-maker status for granted, Built is the Museum’s attempt to assert itself as a great enough authority to not only say what is worth the audience’s time, but to lay out the foundations of the modern architecture canon. Mock, curator of Art in Progress‘ architecture section, uses her introduction to set-up a vision of the “modernist architect” as an individual whose work can walk in perfect balance between “present conditions and future needs.” (9) The utopian-minded ‘modernist architect’ works at odds with the skeptical public, who can only think of the “heat bills” and “glare” that result from the glass-heavy modernist home design. To Mock, these shallow critiques of modern architecture are born out of ignorance, critics who think all of modern architecture can be reduced to “large areas of glass.” (21) Her introduction posits a conflict between the modern style and the cult of practicality. Written in wartime, Mock condemns the point-of-view that states that architects are only there to provide “trimmings,” using the fifty examples in the text to show how architects straddle the line between the practical and the aesthetic. (9)

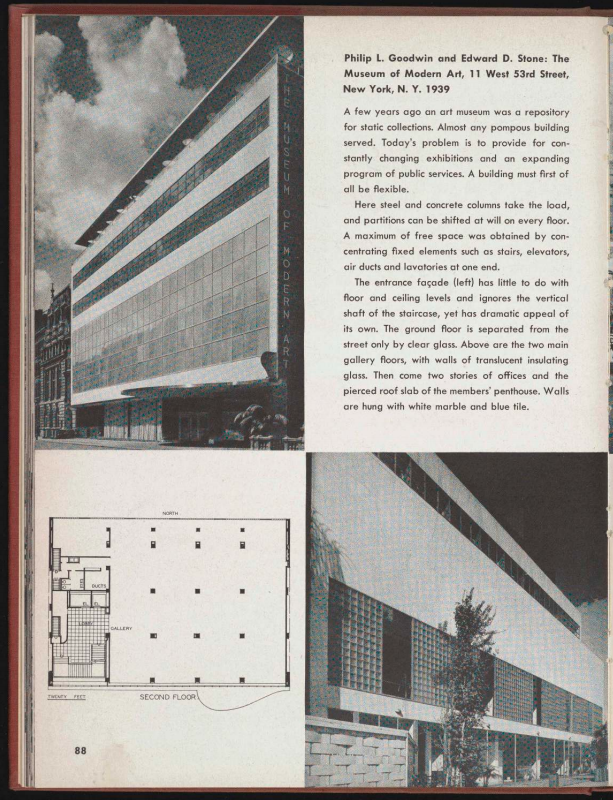

The subsequent two-thirds of the text showcase the fifty American buildings highlighted in the exhibit. Including several photographs of each structures’ interiors and exteriors, Mock also includes a basic floor-plan. Alongside the visual aspects, Mock features critical notes for each work highlighted. The book functions as a useful source if you are looking for contemporaneous reactions to buildings like “Falling Water” or “The Red Rock Amphitheater.” Perhaps the most striking choice in the text, considering the publisher, is Philip L. Goodwin and Edward D. Stone’s design for the Museum of Modern Art. Praising the architects, the notes also make a point to distinguish the museum as a “flexible” museum, distinguishable and new from the “static collections” that defined art museums in the past. (88) Built writes of the Museum’s architecture as essential to its functionality as a new type of museum.

For additional context around Art in Progress and Built in U.S.A., the Museum of Modern Art has recently provided scans of the three 1944 press releases promoting both to the general public. The best of the three articulates the goals of Built so well it is just as good of an introduction as anything within the text itself. Starting off with a quote from Park Commissioner Robert Moses debasing the Municipal Asphalt Plant (highlighted in Art in Progress and Built) as “horrible modernistic stuff,” the Museum holds it in regard as “one of the buildings… which best represent progress in design and construction during the past twelve years.” In the press release, Moses functions as a real-world version of the abstract ‘public’ Elizabeth Mocks talks about in her introduction. In openly clowning this establishment figure, the Museum not only heaps praise upon the artist, but on itself as a taste-maker. Built in U.S.A., and the marketing surrounding the exhibit and text, establishes an ‘us vs. them’ narrative with the stakes being the aesthetic, and the soul, of a nation. All of the materials the Museum of Modern Art has shared related to the Built in U.S.A. section of Art in Progress are essential to understanding what the discourse surrounding architecture was like in the mid-20th century.

You can read Built in U.S.A. in our Special Collections (or even in the PCL stacks!). Or you can read a PDF (as provided by the Museum of Modern Art) here, further exploration of the Built in U.S.A. section of the Art in Progress exhibit can be found here.