John Carter. Specimens of Gothic Architecture and Ancient Buildings in England; comprised in one hundred and twenty views, drawn and engraved by John Carter. London: E. Jeffery and Son, 1824.

Continuing with my theme of tiny, pocket-sized books, I selected Carter’s Ancient Buildings in four volumes, which are 12cm x 9cm. John Carter (1748-1817) wrote extensively on the medieval buildings of England as an advocate for “Gothic” as the national style and the conservation of these monuments, primarily in Gentleman’s Magazine (J. Mordaunt Crook, ‘Carter, John (1748–1817)’). J. Mordaunt Crook writes of John Carter:

Carter’s contribution to the Gothic revival was neither academic, nor, strictly speaking, archaeological, nor even antiquarian. It was essentially inspirational…. In Carter’s career we sense a fundamental shift of taste: the birth pangs of Victorian Gothic; the changing sensibility of a whole generation focused through the eyes of one man- England’s first ‘architectural correspondent’. By the end of his life he had become almost a living document; a link between the world of Strawberry Hill and the world of A. W. Pugin. (J. Mordaunt Crook, John Carter and the Mind of the Gothic Revival, 59-62)

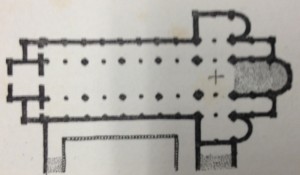

The volumes are arranged alphabetically by county, and one can imagine an antiquarian or enthusiast slipping the tiny volume into his pocket as his guide to English architecture. The northern regions of York, Durham, and Cumbria, however, are neglected. Carter documented a wide variety of buildings: cathedrals, chapels, castles, palaces, gates, kitchens, hospitals, barns, and monastic buildings. Each plate includes either a description of the work or a brief history of the site. Perhaps the most surprising inclusions, despite the “Ancient” in the title, are Stonehenge and Glastonbury Tor.

Crook, J. Mordaunt. John Carter and the Mind of the Gothic Revival. London: The Society of Antiquaries of London, 1995.

J. Mordaunt Crook, ‘Carter, John (1748–1817)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/4791, accessed 30 Jan 2014].