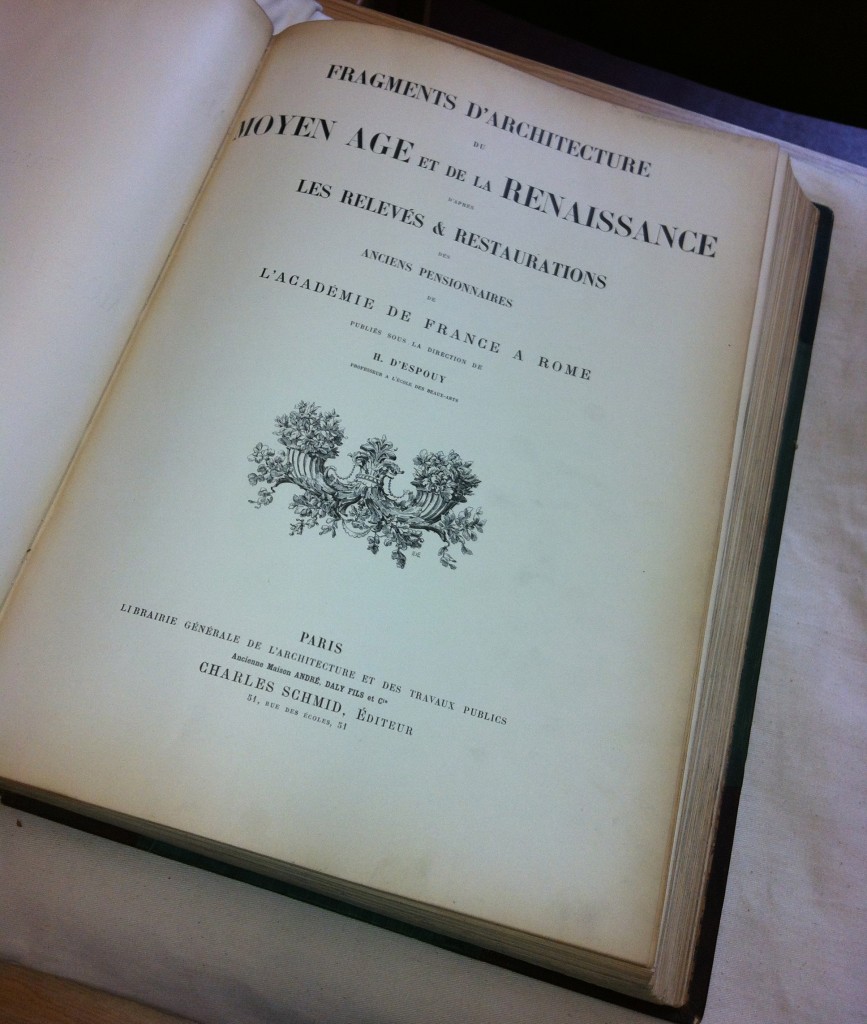

Georgiana Goddard King. Mudejar. Bryn Mawr: Bryn Mawr College, 1927.

New territory again this week: Medieval Spain. I must confess that I know little about this subject. Whenever I teach medieval survey, my discussion of medieval Spanish architecture has been limited. I only tend to lecture on the architecture of Spain as it relates to Compostela and the Pilgrimage Routes or to the Architecture of Islam with the Great Mosque of Cordoba as an example. After my last round of medieval survey, I resolved to revamp my course to include more diverse topics, to expand further into areas in which I am less knowledgeable, and to move away from the traditional canon. So I bring you Georgiana Goddard King’s Mudejar.

Georgiana Goddard King (1871-1939) both studied and taught at Bryn Mawr. Her work was in the English Department initially, but she would eventually establish the Department of Art History at the college. (“King, Georgiana Goddard,” Dictionary of Art Historians). Harold E. Wethey writes of her passing in Parnassus, “At Bryn Mawr Miss King became a tradition and cult; and now she is a legend.” (Wethey, 33) He discusses at length the contributions she made to the field of art history. He notes:

Mudejar, which the author considered her best book, is an inclusive study of that peculiarly Spanish style, which she analyzed in relation to history and culture, as well as to earlier Spanish monuments and to Islamic sources. (Wethey, 34)

Georgiana Goddard King’s works, especially that of Mudejar, seem like a natural place to begin for those interested in pursuing medieval Spanish architecture, as she was an founding member of the field of study. In the preface she positions this work against an earlier definition of “Mudejar” that she herself established. She quotes her initial definition:

Mudejar is a dangerous word, easier to use than to account for. It implies brickwork often, and plaster, being applicable to those forms of art where the material is contemptible and perishing, and the work is more utterly priceless; it implies cusping always, and usually an interlace of forms, and horseshoe arches where practicable. The character is apparent in the colored tile and cut plaster and inlaid wood of King Peter’s building at Tordesillas and in Alcazar at Seville; in the modified flamboyant of King Henry’s building in the region of Segovia, even to the strange fleeting and restlessly-recurrent yet baffling designs of the vault in the cathedral there; in the brick towers and apses at Toledo and Calatayud. Whenever and wherever it was executed it bears the sign that a different and non-European imagination was at work, in the use of color, in the invention of the composition, and in the very shape and curves and angles. It is visibly unlike to other things, as art-nouveau is, and steel structure. It can hardly be defined more exactly; but it can be recognized. It gives always a special pleasure, of delicacy, intricacy, subtlety, incredible elusive refinement. Like other things that came out of the East, it is always a little intoxicating. (King, vii-viii)

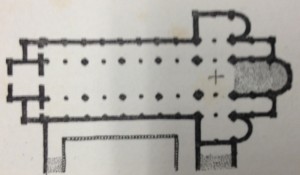

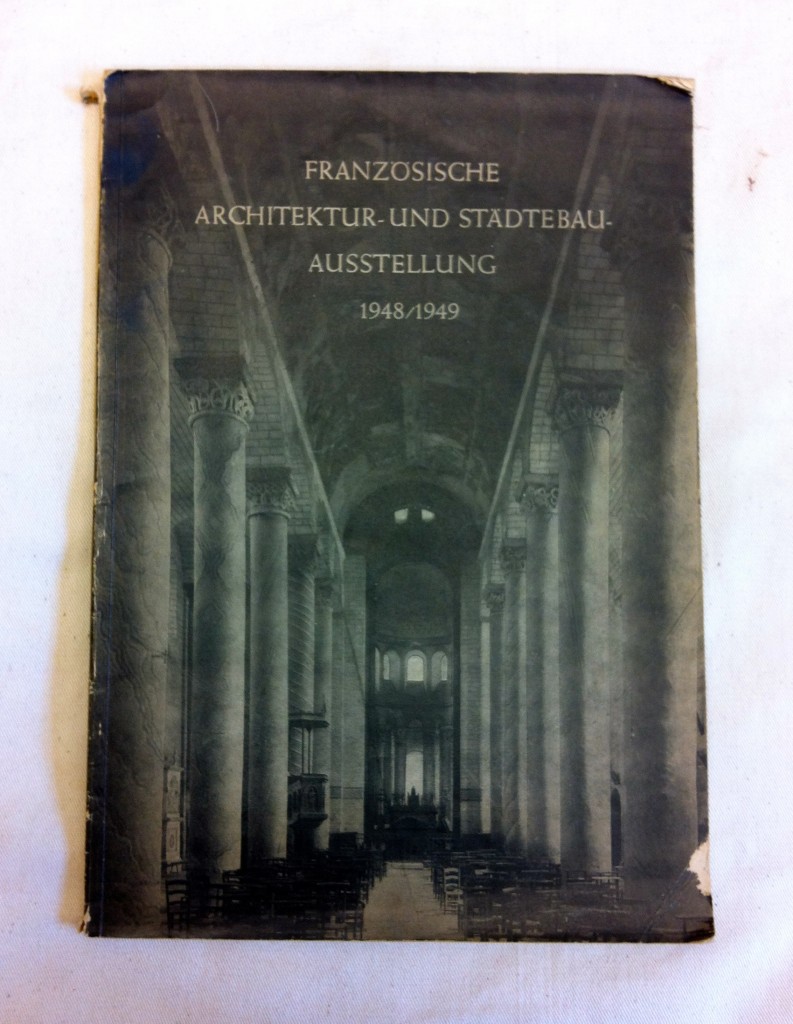

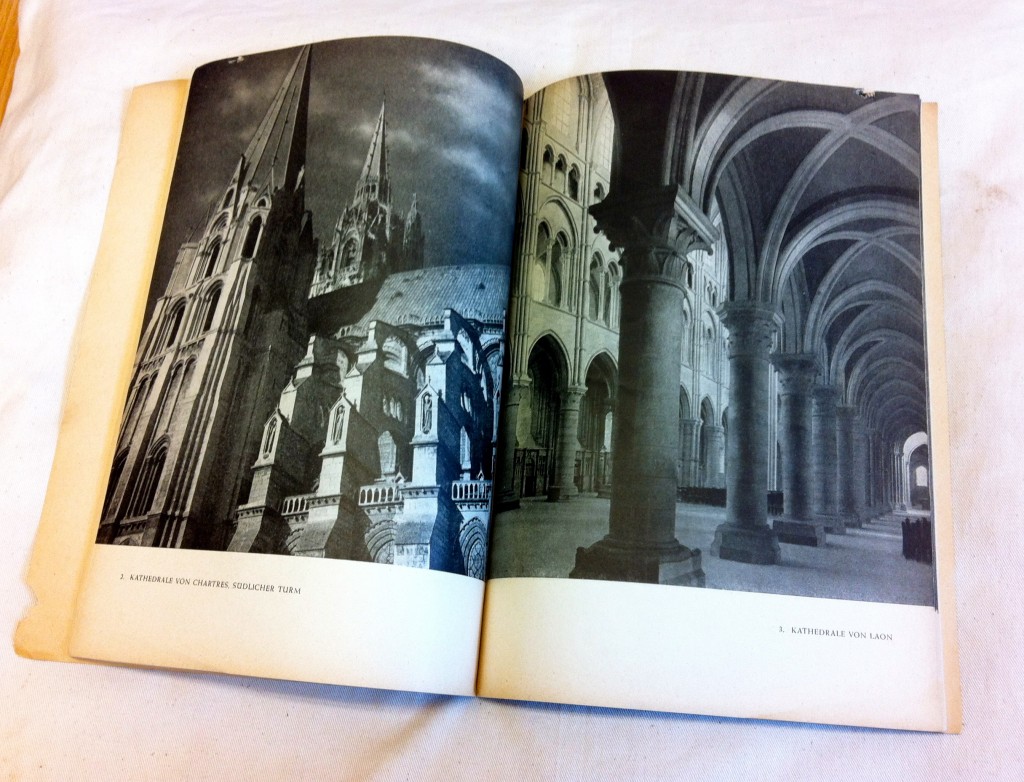

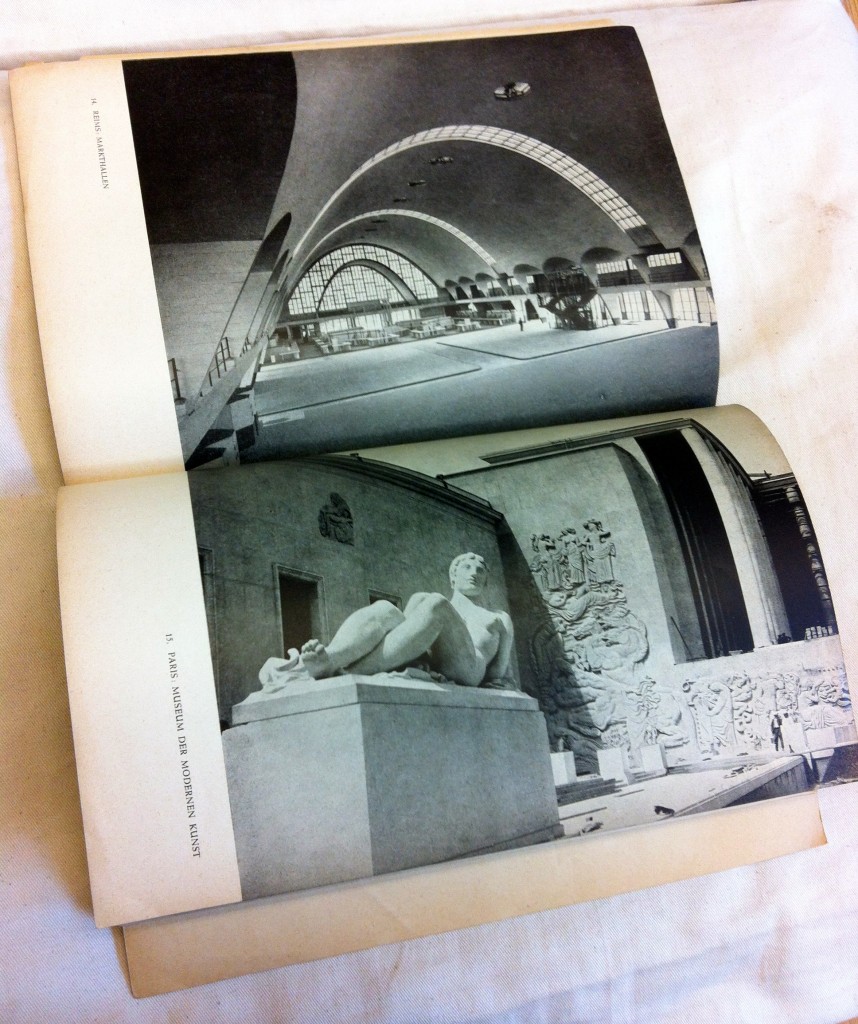

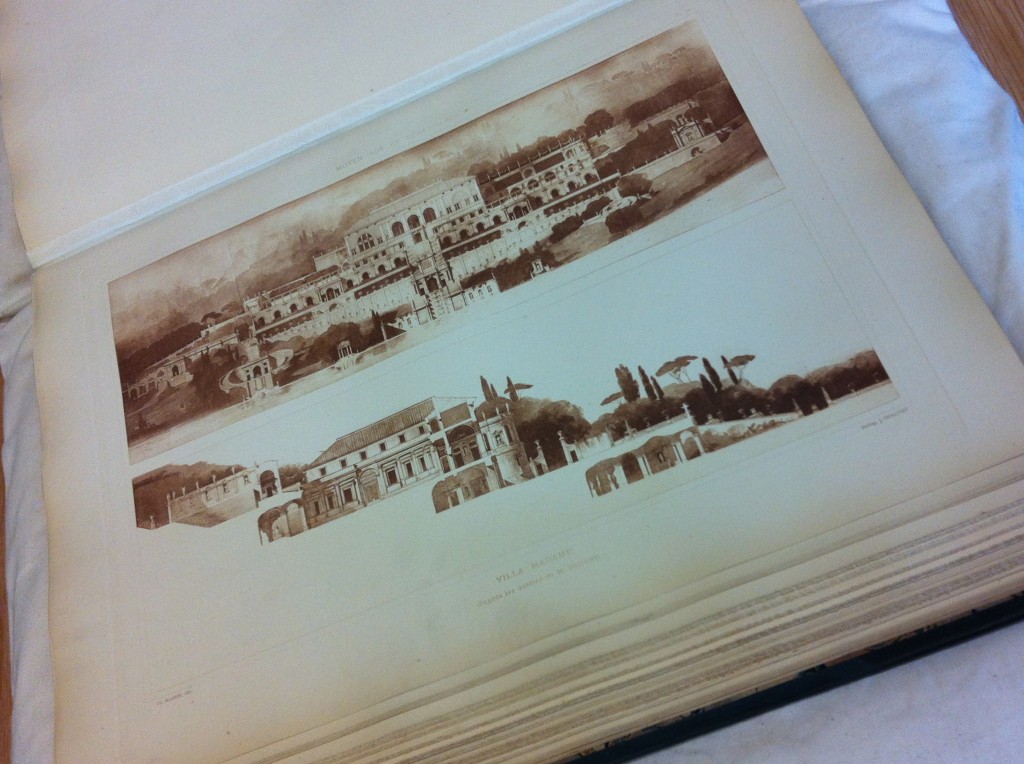

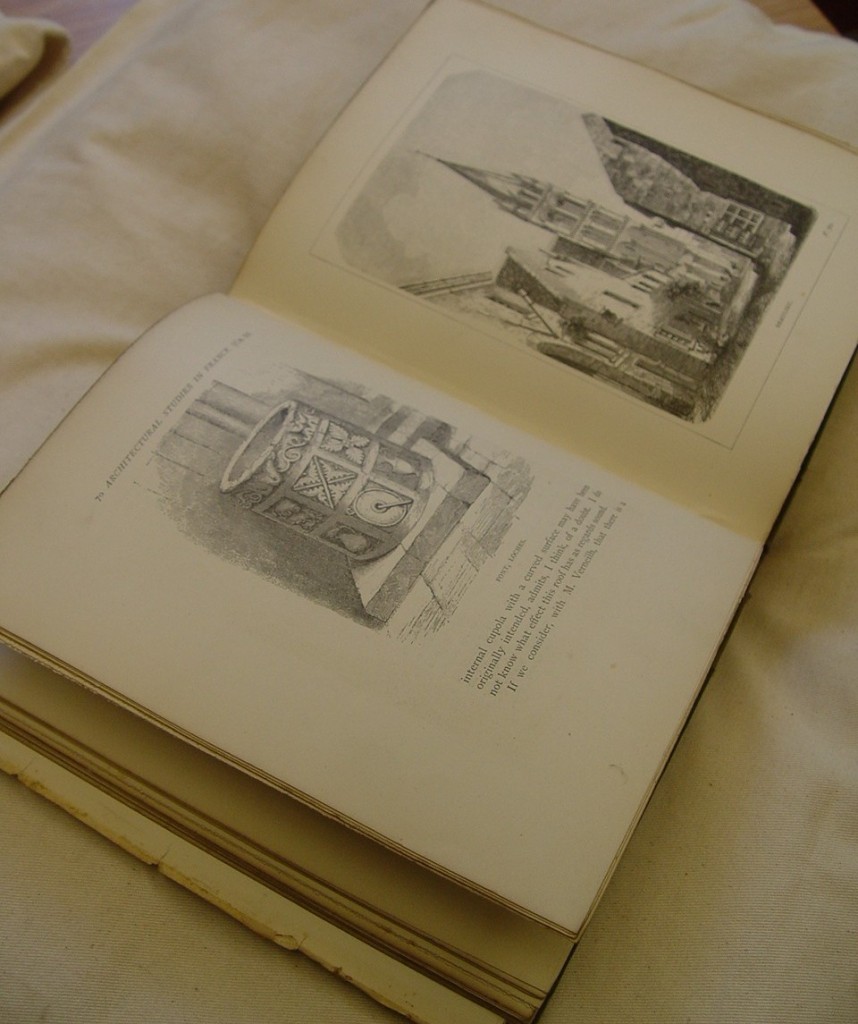

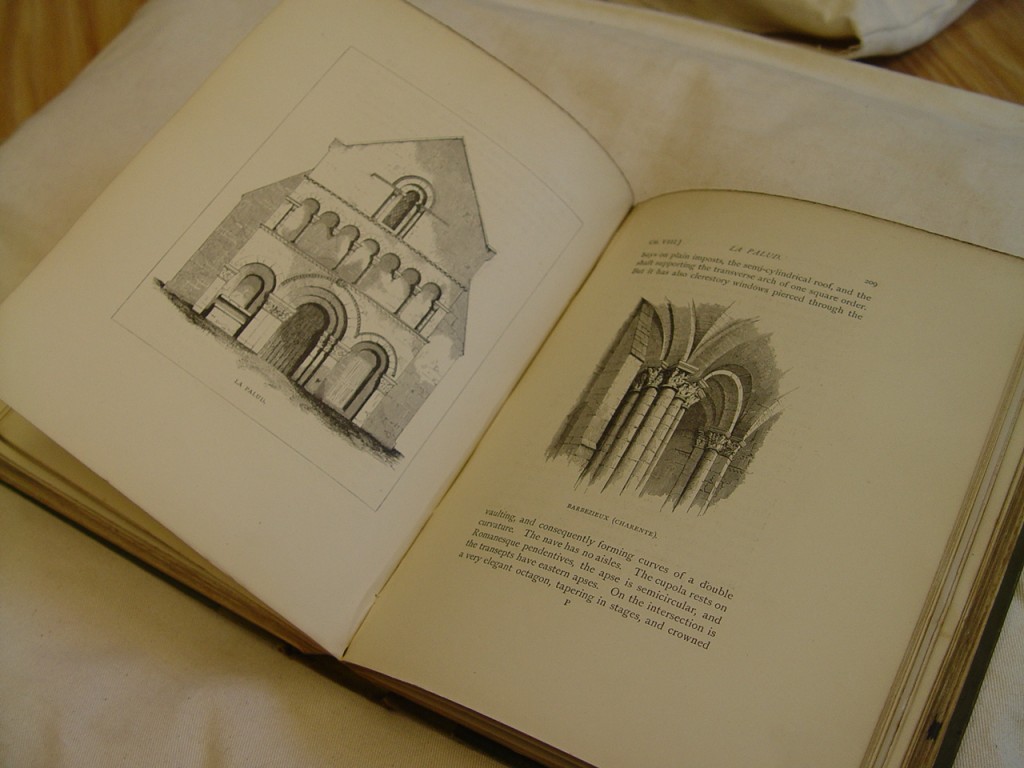

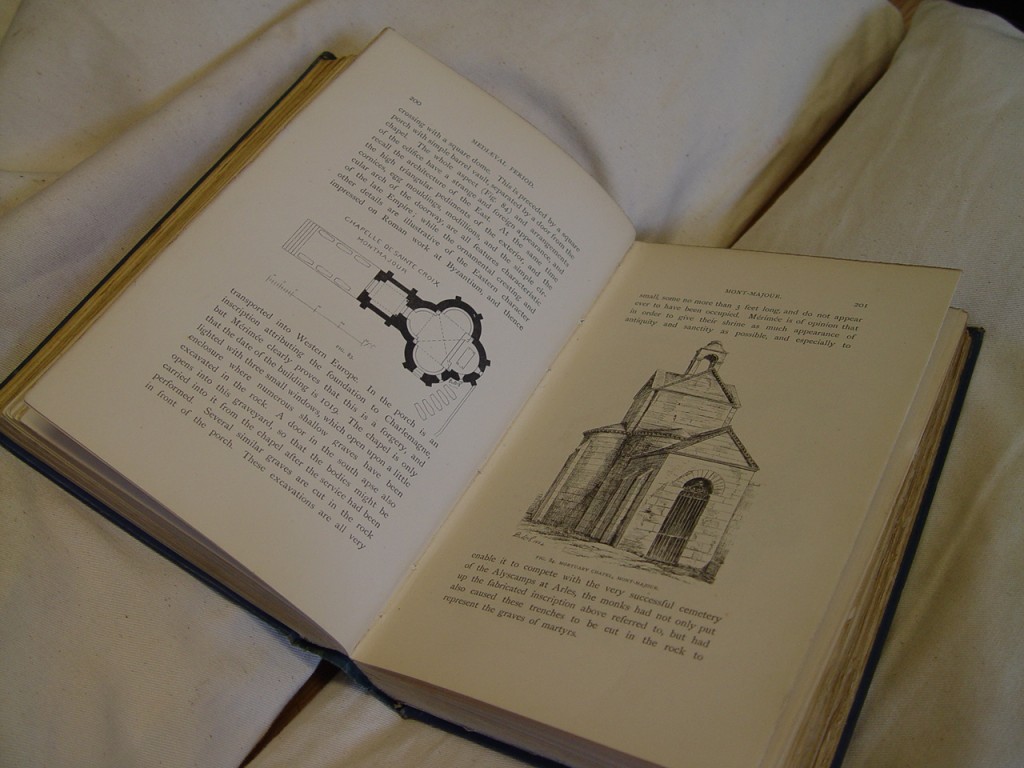

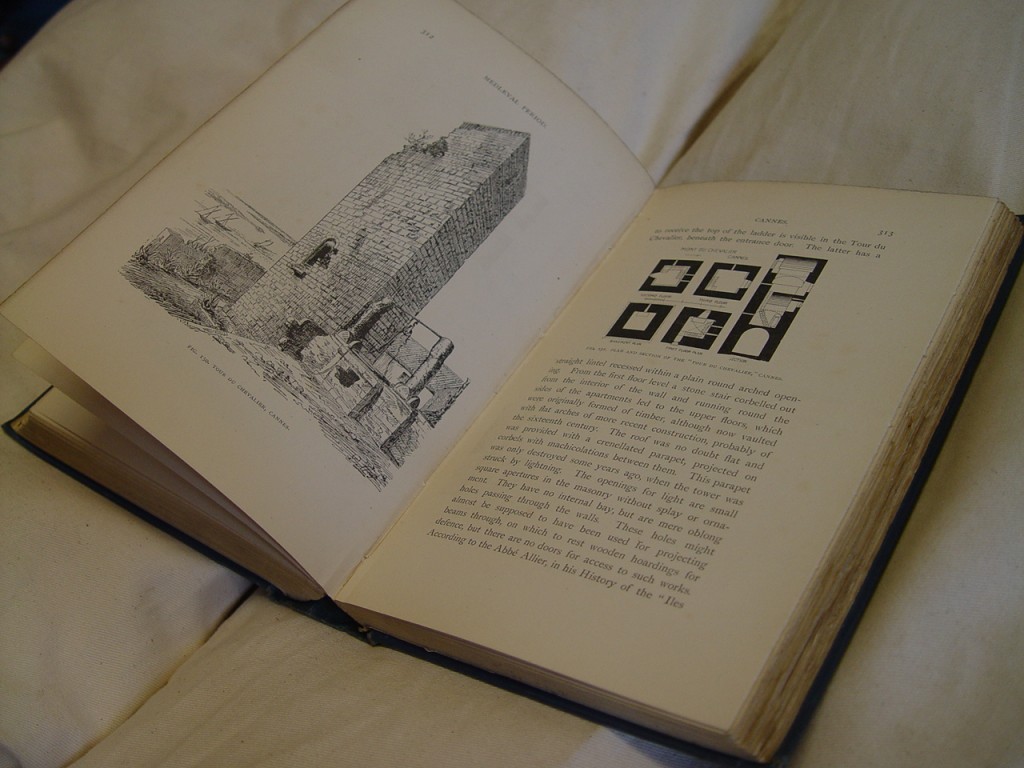

This is where we must begin. King organizes her work into sections which address the History, Characteristic Features, Materials, Secular Buildings, Style, and lastly Other Arts. The work is also highly illustrative with both photographs and drawings.

“King, Georgiana Goddard.” Dictionary of Art Historians (website). http://www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org/kingg.htm, accessed August 7, 2014.

Harold E. Wethey. “An American Pioneer in Hispanic Studies: Georgiana Goddard King.” Parnassus 11.7 (1939): 33-35.