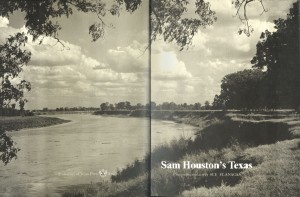

Sue Flanagan’s book Sam Houston’s Texas “attempts to place Houston in proper perspective against the backcloth of past events and to show him still a part of the changing pattern of our time” (pg. ix). The book is organized chronologically, running from 1832 to 1863, with a chapter devoted to each year. Included in every chapter are photographs of relevant buildings and the Texas landscape, as well as historical context for the year, based mostly in primary sources from the era.

Sue Flanagan’s book Sam Houston’s Texas “attempts to place Houston in proper perspective against the backcloth of past events and to show him still a part of the changing pattern of our time” (pg. ix). The book is organized chronologically, running from 1832 to 1863, with a chapter devoted to each year. Included in every chapter are photographs of relevant buildings and the Texas landscape, as well as historical context for the year, based mostly in primary sources from the era.

Beginning in 1832, Flanagan examines Houston’s childhood in Virginia, his time as a Congressman and Governor in Tennessee, and as a delegate for the Cherokee Tribe to Washington. Houston came to Texas to buy up land and serve as an envoy to Native Americans in the territory, a role assigned to him by then-President Andrew Jackson. Moving year-by-year, Flanagan details the increasing dissatisfaction in Texas with Mexican governance, Houston’s rise to General of the Texas army, the price of Texas independence, and the early years of the Texas Republic. One of the longest chapters is the one on 1836, the year Texas won independence from Mexico, featuring discussion of the Battle of the Alamo, the massacre of all inside the mission, and the subsequent surrender of Santa Anna to Houston less than two months after the loss of the Alamo. Houston declared on March 2, 1836, that “Independence is declared; it must be maintained.” Houston recognized that once Texas was free of Mexico, its best chance of maintaining independence was joining the United States. However, before Texas joined the Union, it was its own nation for ten years, with Houston remaining a prominent leader throughout, serving twice as President of the Republic of Texas, a Senator to the US Congress, and Governor of Texas. Flanagan’s book ends in 1863, the year of Houston’s death. Throughout this narrative are photographs of relevant places and spaces, showing the Texas Houston fought for and loved so dearly.

Published in 1964, Sam Houston’s Texas came just over 100 years after Houston’s death and just short of 100 years of the start of the Civil War. Houston foresaw the Civil War, and feared that secession and alliance with the Southern states would irreparably damage Texas and the United States. Instead, he thought Texas would fare better as its own empire if it conquered Mexico. With this in mind, as Governor of Texas,  Houston refused to secede from the United States. This stemmed not from a belief in abolition (Houston himself owned slaves) but rather from his wish to avoid more war on Texas soil. As a result, Houston was forced out as Governor and replaced with someone more sympathetic to the Confederate cause. Much like in the 1860s, the 1960s were filled with racial tension and turmoil. President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Texan, passed the Civil Rights Act the same year that Sam Houston’s Texas was published, a reminder of how much had changed in the last century for the state and the nation.

Houston refused to secede from the United States. This stemmed not from a belief in abolition (Houston himself owned slaves) but rather from his wish to avoid more war on Texas soil. As a result, Houston was forced out as Governor and replaced with someone more sympathetic to the Confederate cause. Much like in the 1860s, the 1960s were filled with racial tension and turmoil. President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Texan, passed the Civil Rights Act the same year that Sam Houston’s Texas was published, a reminder of how much had changed in the last century for the state and the nation.

Sam Houston’s Texas is a fascinating look at Sam Houston himself, as well as the indelible mark he left on Texas. Houston is an incredibly complicated figure: a representative for Native American rights, yet an advocate for slavery; a believer that Texas should be in the United States while also wanting Texas to be a great nation in its own right; a war hero who wanted to avoid war at all costs in later life. He was the first President of the Republic of Texas, a U.S. Senator for Texas, the man who made Santa Anna surrender and won Texas’ independence in a battle lasting only 18 minutes against a seemingly unstoppable Mexican Army, and he is the namesake for the city of Houston. The tales of Sam Houston are larger than life. Flanagan’s book reveals the man who inspired the legends. Using Houston’s own words, letters, and accounts from others who knew him, Flanagan shows Houston to be a complicated and flawed, yet remarkable man. In short, Houston was human, with all the complexities and contradictions that come with the human experience.

Many Americans have gone through a reckoning in recent years, realizing that the Founding Fathers were not infallible men. For years they have been literally placed on pedestals, had cities, buildings, and monuments named for them and built in homage to them, with few questions asked about who they were beyond the iconic image. Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and many of the other Founding Fathers preached the values of liberty and equality while owning slaves. This does not make them entirely unworthy of admiration, but it does mean that Americans must recognize that they were imperfect men who accomplished exceptional things. Texans must face a similar reckoning with their heroes, and Sam Houston’s Texas is an excellent start to rewriting that historical narrative. Houston was all things: a friend to Native Americans, a slave holder, an American, a Texan, a leader of the Texas Revolution, and an advocate against the Civil War. These seemingly contradictory traits make Houston a more tangible, relatable figure. Sam Houston the legend provides an unattainable vision of what it means to be human. Sam Houston the man, with all his flaws and contradictions, provides a realistic example to which Texans can aspire. Sam Houston will forever live on in Texas folklore, but it is time to separate the legend from the man. It may be simpler or more appealing to tell tales of Houston as a perfect, Arthurian icon who led Texas to independence, but the truth of the man behind the legend is a far more fascinating story.