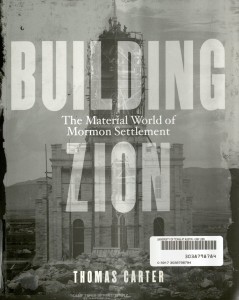

There are so many amazing news books at the Architecture and Planning Library this week, one book just was not enough to feature in a blog post. So this week’s highlights are Building Zion: The Material World of Mormon Settlement by Thomas Carter, and The Optimum Imperative: Czech Architecture for the Socialist Lifestyle, 1938-1968 by Ana Miljacki.

Carter’s Building Zion explores the differences and continuities between traditional American architecture and Mormon architecture, as well as the drastic contrast in style between Mormon temples  and Mormon homes. Carter’s book reveals a fascinating conundrum: Mormon temples are designed to stand out, while Mormon homes are meant to blend in with a typical family home in the United States. The temple is a physical representation of the uniqueness of the Mormon faith, yet the home downplays the polygamous nature of some Mormon families. Carter also explores that even though the homes of Mormons in Utah were designed to house a larger family, sometimes with each wife living in a wing with their children, the homes are surprisingly typical in style and size. This reflects the desire of many Mormon families to fit in. Before migrating to Utah, Mormons were sometimes ostracized or even persecuted in their communities; considering this history, it is perfectly understandable that Mormons would seek to stand out as little as possible in their family life, as it was polygamy that bothered many opponents of the faith. So then, why make the temples stand out so? This is exactly what Carter explores in Building Zion, as well as the realities of daily life in Mormon settlements.

and Mormon homes. Carter’s book reveals a fascinating conundrum: Mormon temples are designed to stand out, while Mormon homes are meant to blend in with a typical family home in the United States. The temple is a physical representation of the uniqueness of the Mormon faith, yet the home downplays the polygamous nature of some Mormon families. Carter also explores that even though the homes of Mormons in Utah were designed to house a larger family, sometimes with each wife living in a wing with their children, the homes are surprisingly typical in style and size. This reflects the desire of many Mormon families to fit in. Before migrating to Utah, Mormons were sometimes ostracized or even persecuted in their communities; considering this history, it is perfectly understandable that Mormons would seek to stand out as little as possible in their family life, as it was polygamy that bothered many opponents of the faith. So then, why make the temples stand out so? This is exactly what Carter explores in Building Zion, as well as the realities of daily life in Mormon settlements.

Miljacki writes on a completely different topic in The Optimum Imperative: Czech architecture from 1938 (when the nation, then called Slovakia, was divided between Hungary, Germany, and  Poland) to 1968 (the time of the Prague Spring, when Czechoslovakia began to liberalize and the Soviet Union invaded to regain control). This is a particularly fascinating time in Czech history, and Miljacki examines how the architecture reflected socialist ideals. Miljacki is not kind to the theory or reality of socialism, arguing that the architecture of the Soviet Union years reinforced and physically imposed socialism, class struggles, and Soviet control on the Czech people. Following the dissolution of Czechoslovakia and establishment of the Czech Republic, there was a renewed emphasis on Czech heritage and culture, presumably architecture, too. Though The Optimum Imperative does not explore beyond 1968, Miljacki provides the necessary context and background to better understand modern trends in the country and its strong dislike of all things Russian.

Poland) to 1968 (the time of the Prague Spring, when Czechoslovakia began to liberalize and the Soviet Union invaded to regain control). This is a particularly fascinating time in Czech history, and Miljacki examines how the architecture reflected socialist ideals. Miljacki is not kind to the theory or reality of socialism, arguing that the architecture of the Soviet Union years reinforced and physically imposed socialism, class struggles, and Soviet control on the Czech people. Following the dissolution of Czechoslovakia and establishment of the Czech Republic, there was a renewed emphasis on Czech heritage and culture, presumably architecture, too. Though The Optimum Imperative does not explore beyond 1968, Miljacki provides the necessary context and background to better understand modern trends in the country and its strong dislike of all things Russian.

While seemingly unrelated, Building Zion and The Optimum Imperative both discuss, broadly, the importance of architecture as an expression of control and culture. For Mormons, while it was critical to them to deemphasize the distinctive nature (to outsiders, the “otherness”) of their large families and polygamous marriages, the temple was an opportunity to physically express that otherness without judgment as a place of worship. The Soviet Union used architecture to reinforce the values of socialism, and thereby their control over Czechoslovakia, which later led to a return of Czech tradition. In both cases, architecture served as an opportunity for cultural expression and as a means of giving the appearance of normality to atypical situations.