Hello! My name is Irene Lule. I work at the Alexander Architectural Archives as a graduate research assistant. I was fortunate to spend my summer interning with the Veterans History Project at the Library of Congress. The Veterans History Project, created by Congress in 2000, “collects, preserves, and makes accessible” the records of our American veterans from World War I to present.[1] My specific project focused on increasing the discoverability of World War I veteran collections through finding aids. A finding aid, as described by the Society for American Archivists, is “a description of records that gives the repository physical and intellectual control over the materials and that assists users to gain access to and understand the materials.”[2] Ultimately, our goal was to create finding aids to facilitate greater use of World War I collections. By the end of my internship, I had encoded 10 finding aids documenting the experiences of World War I veterans. As someone not too well versed in the United States’ role in World War I, I could not have asked for a better educational experience. To learn more about my experience at the Veterans History Project and the veterans I worked with, read my two blogs for the Library of Congress about soldier homecomings and WWI-era postcards. As Junior Fellows, we presented our projects to Library of Congress staff and the public. Check out the picture of me (in the blue dress) below on Display Day!

Photo by: Shawn Miller for the Library of Congress

Photo by: Shawn Miller for the Library of Congress

After returning to The University of Texas at Austin (UT) campus for the fall semester, my experience with World War I archival material increased my awareness of the university’s World War I history. Tomorrow marks the 79th anniversary of Veterans Day. Enacted in 1938, the holiday also marks Armistice Day in other countries.[3] Along with being the first “modern” war, America mobilized over 4,000,000 soldiers in two years and suffered over 100,000 casualties during World War I.[4] While typically associated with the Vietnam War, a majority of these men were conscripted (drafted) from all over the United States.[5] On November 11, 1918, an armistice was signed between the Allied and Central Powers ending the fighting in World War I. Memorials to the American soldiers of World War I are seen throughout the UT campus since post-WWI years marked a period of tremendous expansion for the university. As time marks away the years, the visual representation of these memorials are not lost. There are several memorials commemorating World War I at UT, including one large stadium. Erected in 1924, the current Darrell K. Royal – Texas Memorial Stadium (DKR) was originally dedicated to all Texans that had served during World War I.[6] Following the successive wars that followed, the stadium was re-dedicated (for a third time) to all Americans soldiers in all wars in 1977.[7] Next time you are near the stadium, stop by the Red McCombs Red Zone to view the plaque listing the names of Texans that perished in World War I and a rendering of a doughboy (slang for an American soldier during World War I).

A rendering of a WWI doughboy outside of the Red McCombs Red Zone.

A rendering of a WWI doughboy outside of the Red McCombs Red Zone.

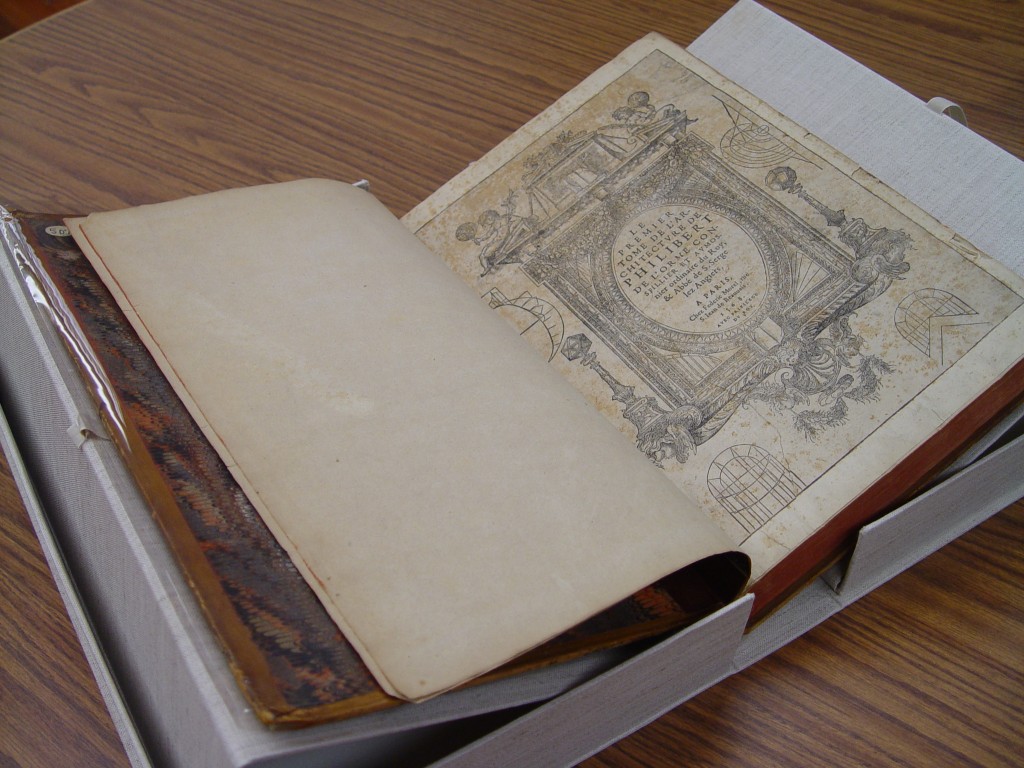

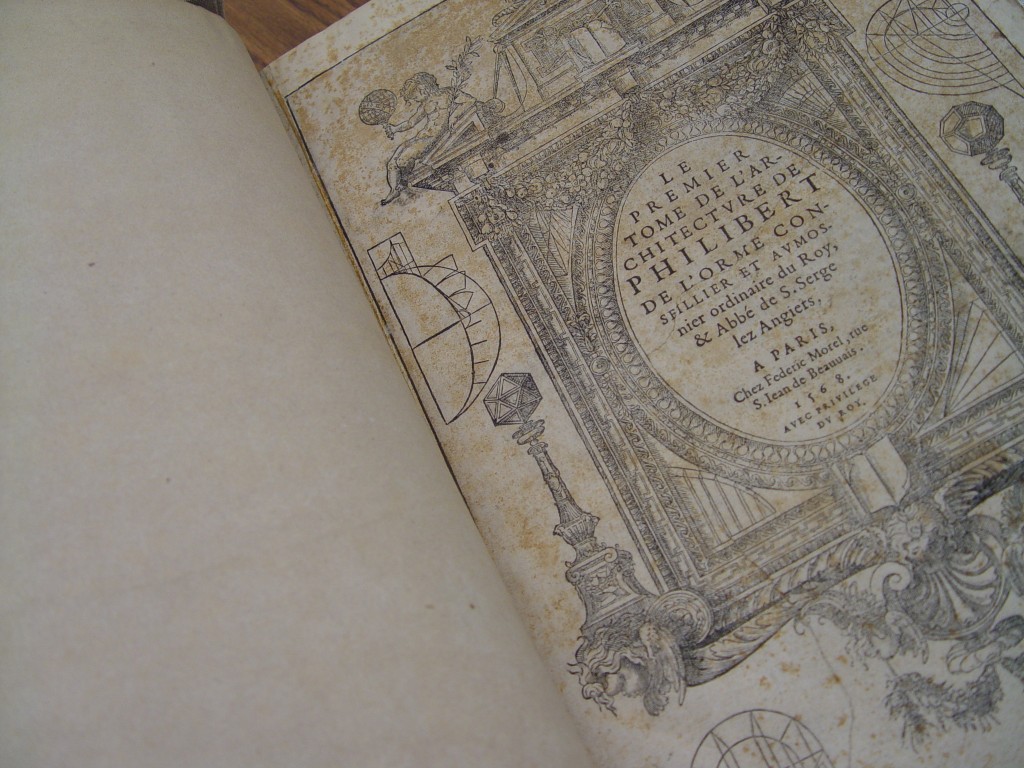

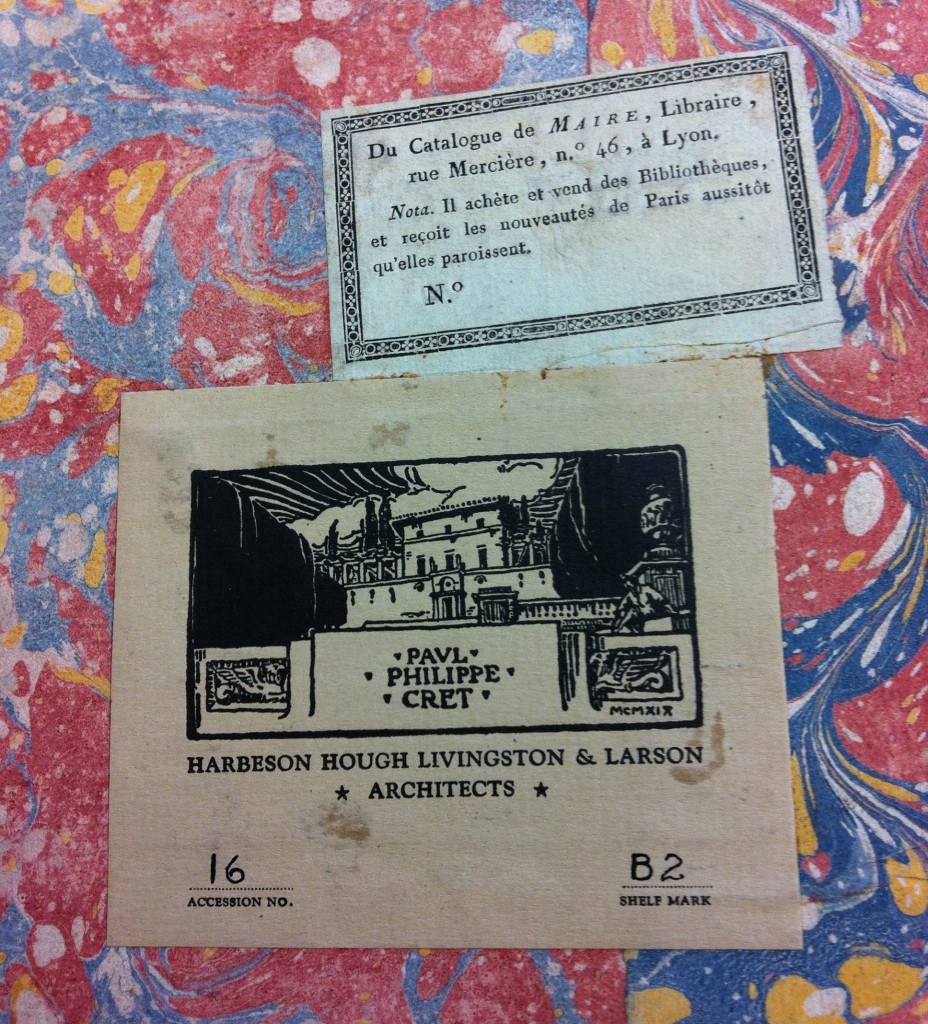

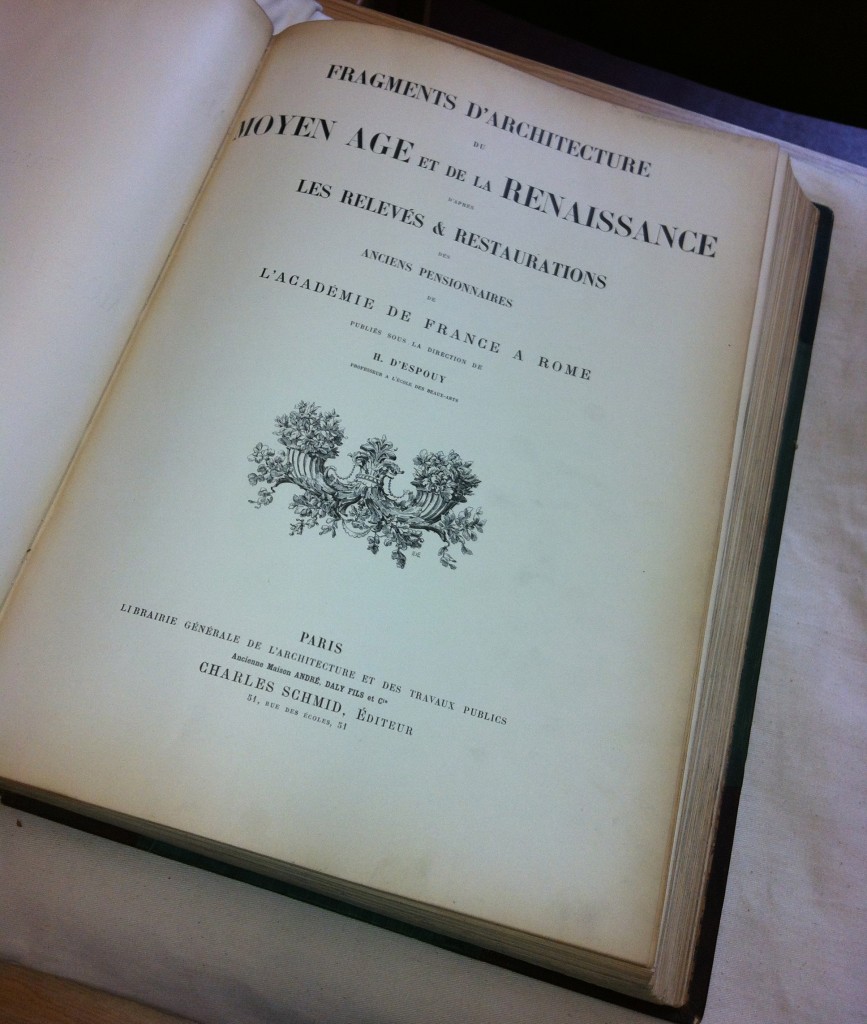

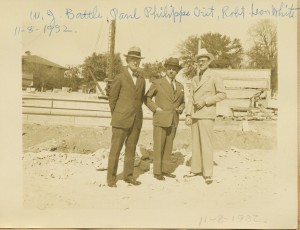

In addition, the Alexander Architectural Archives contains archival material related to the World War I memorials designed by Philippe Cret. Paul Philippe Cret, a prominent architect hired by the UT administrators to create a master plan for the University and design the Main Building, has an interesting connection to World War I. A noted architect, Cret was born and raised in France.[8] He relocated to Philadelphia to teach architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, but still visited France during the summers with his wife.[9] With the breakout of World War I in June 1914, Cret, at the time in France, joined the French army, where he remained for the duration of the war.[10] Cret actually “suffered from serious deafness as a result of his service in World War I.”[11] Following his service, Cret was commissioned by the American Battle Monuments Commission to design World War I memorials. The Alexander Architectural Archives has an extensive collection containing Cret’s drawings, photographic material, and papers predominantly related to his work with the University of Texas as well as materials related to his work involving World War I memorials. The following paragraphs will discuss some of these materials from the Littlefield Fountain and Chateau-Thierry Memorial.

Cret (in the middle) with William Battle and fellow architect, Robert Leon White (WWI veteran) at UT Austin on November 8, 1932.

Cret (in the middle) with William Battle and fellow architect, Robert Leon White (WWI veteran) at UT Austin on November 8, 1932.

As mentioned before, much of our most UT iconic structures can be credited to the post-WWI years. One of these is the Littlefield Fountain, which was constructed following a donation from Major George W. Littlefield. Created in the context of Southern remembrance, the fountain’s history is extensive and complicated. Littlefield originally imagined an arch lined with the “figures important to Texas and Southern history.”[12] Pompeo Coppini redesigned Littlefield’s idea to be a fountain commemorating World War I with the (now removed) Confederate statues surrounding the fountain as a “monument of reconciliation portraying World War I as the catalyst that inspired Americans to put aside differences lingering from the Civil War and unite in carrying the torch of liberty to the Old World.”[13] Paul Cret came into the Littlefield Fountain process well after its inception, but as the consulting architect for the university, his approval was crucial. He reorganized the location of the Confederate statues away from the fountain and along the mall where they remained until August 2017.[14] After years of back and forth, Littlefield’s death in 1920, and various other issues, the Littlefield Fountain was unveiled in 1932 with both Littlefield’s and Coppini’s original intentions “hopelessly blurred.”[15]

There are several features of the fountain that are very obviously about World War I. Alongside the side of Columbia, there is a soldier and sailor on her sides.[16] The back of the fountain contains a plaque listing the “Sons and Daughters” of the university that died in the Great War.

The sailor, located on the right side of Columbia, on the Littlefield Fountain.

The sailor, located on the right side of Columbia, on the Littlefield Fountain.

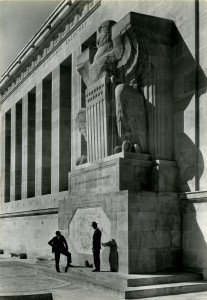

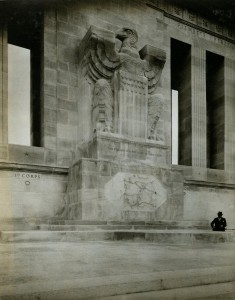

Located just outside of Chateau-Thierry, France, the Chateau-Thierry Monument “commemorates the sacrifices and achievements of American and French fighting men in the region, and the friendship and cooperation of French and American forces during World War I.”[17] The photograph below depicts an eagle with a map of the region (designed by Cret) nestled underneath.

Along with “heroic sculptured figures representing the United States and France,” the monument is a double colonnade rising above the valley of the Marne River.[18] The American Battle Monuments Commission has digitized the 1937 dedication of the monument on YouTube, which includes a speech by General John J. Pershing! The photograph below depicts an eagle with a map of the region (designed by Cret) nestled under from a scrapbook in the Cret collection.[19]

Another angle of the eagle. All three World War I memorial photographs are from a scrapbook in the Cret collection.

Another angle of the eagle. All three World War I memorial photographs are from a scrapbook in the Cret collection.

Cret was also commissioned for World War I monuments in the United States. Below is photograph of the Providence World War I Memorial in Providence, Rhode Island.

A World War I memorial, also designed by Cret, in Providence, Rhode Island.

A World War I memorial, also designed by Cret, in Providence, Rhode Island.

In addition to the Paul Philippe Cret collection, the Alexander Architectural Archives contains several collections from World War I veterans including Ralph Cameron, Theo S. Maffitt, Preston M. Geren, and Robert Leon White. Cameron and Maffitt also served during World War II with the Corps of Engineers. Most of these collections focus on the veteran’s career as an architect with some exceptions.

Next time you find yourself on the 40 Acres whether it is walking to class, rushing to a meeting, or watching the Longhorns play in DKR, take a moment to reflect on the memorials and read the names of UT’s past.

References:

[1] “About the Project,” Veterans History Project, accessed November 7, 2017, https://www.loc.gov/vets/about.html.

[2] “Finding Aid,” Society of American Archivists, accessed November 7, 2017, https://www2.archivists.org/glossary/terms/f/finding-aid.

[3] “Veterans Day,” Wikipedia, accessed November 7, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veterans_Day.

[4] “United States in World War I,” Wikipedia, accessed November 6, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_in_World_War_I.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Handbook of Texas Online, Richard Pennington, “Darrell K. Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium,” accessed November 06, 2017, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/xvd01.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Paul Philippe Cret papers,” University of Pennsylvania, accessed November 6, 2017, http://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/ead/detail.html?id=EAD_upenn_rbml_MsColl295.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Jim Necar, “Symbolism Amok,” Alcalde, May/June 2001, 80.

[13] Speck, Lawrence W., and Richard Louis. Cleary. The University of Texas at Austin: an architectural tour. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2011, 88.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Speck, Lawrence W., and Richard Louis. Cleary. The University of Texas at Austin: an architectural tour. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2011, 87.

[17] Elizabeth Nishiura, American Battle Monuments: A guide to military cemeteries and monuments maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission (Detroit: Omnigraphics, Inc., 1989), 4.

[18] “Chateau-Thierry Monument,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed November 6, 2017, https://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials/europe/chateau-thierry-monument#.WgB5PGhSyUk

[19] Elizabeth Nishiura, American Battle Monuments: A guide to military cemeteries and monuments maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission (Detroit: Omnigraphics, Inc., 1989), 50.