Irene here with a post about a trip to the Buckeye State, Ohio! In early October, several members of the Alexander Architectural Archives attended the 40th anniversary conference of the Society for Commercial Archeology (SCA) in Cincinnati, Ohio. If you wish to learn more about the processing of the SCA collection, please read my previous post. Along with educating the organization about the processing portion, we were also there as an outreach measure for both monetary and archival material donations. My supervisor, Stephanie Tiedeken, Archivist for Access and Preservation, and I co-presented on the project during the paper sessions. Beth Dodd, Curator of the Alexander Architectural Archives, also attended the conference. Along with presenting, we were also fortunate to participate in tours focusing on the history of Cincinnati and the surrounding area.

Day 1

We arrived on Wednesday, October 4th for the opening reception at the Washington Platform Saloon & Restaurant. After dinner, those brave enough to climb several hundred feet below the surface visited lagering cellars that exist below many structures. Cincinnati had a very active brewing business in the 1800s until the Prohibition Era. The tour guide noted that Cincinnati is thought to have the largest underground system of these cellars in the United States.

Day 2

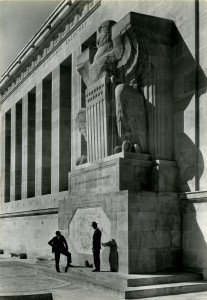

The next day consisted of a tour of Cincinnati. We toured the Carew Tower, which was the tallest building in Cincinnati until 2010. We were treated with wonderful views of the surrounding area.

After, we loaded up on the buses and visited one of Cincinnati’s historic neighborhoods, Over-the-Rhine. As mentioned before, the city had an active brewing economy mostly due to the large amount of German immigrants that came into the area. The tour consisted of us walking around the neighborhood and learning about the influence of German immigrants in society and the local economy. Additionally, architecture is a big theme with SCA. Walking around Over-the-Rhine provided an interesting way to see first-hand the evolution of architecture from then to now. We also visited more underground lagering cellars.

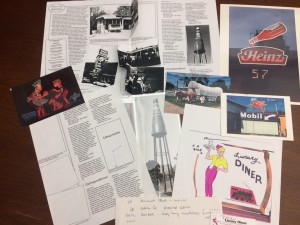

We also stopped at a restaurant where the owner had covered the outside facade and lawn area with neon signs. The one below is one of my personal favorites of the whole trip.

The best part of Day 2 was the 40th anniversary dinner at the American Sign Museum. Along with the wonderful food (including a tasty mac and cheese bar!), Tod Swormstedt, a former SCA board member, gave a very detailed tour of the space. The ambiance coming off the lights really created a wonderful atmosphere to celebrate the 40th year of SCA. Check out all of the fantastic neon signs.

Day 3

Friday was the presentation of the papers. I had never presented at a conference before, so the nerves were quite high. Stephanie and I were in the third session of papers, The 20th Century Roadside in the 21st Century. The two other paper sessions were Exploring the History of Cincinnati and the Buckeye State, and History and Preservation of the American Roadside. Each presenter was allotted 20 minutes to present with a 20 minute Q&A after each paper session. I am happy to report that our presentation went very well. I tried to slow down and focus on positive faces on the crowd. We received a lot of questions about the SCA collection from the audience. Following the paper sessions, Neon, a documentary covering the history of neon in the United States was shown.

Day 4

The focus of Day 4 was a tour of the Dixie Highway, one of the first major highways in the United States. We loaded up on the buses at 8 am and began our travels to Lima, Ohio. Along the way, we stopped at various regional mom-and-pop shops including Kewpee Hamburgers for a late lunch. We also stopped at businesses with interesting signs as seen below. The day concluded with the closing dinner at the Mecklenburg Gardens for a German dinner.

The context for why we attended this conference was centered on acquiring additional SCA archival material, but also educating others about what the Alexander Architectural Archives does as an archive. Many times I have had to explain what an archive does and how archivists operates within such an institution. The opportunity to speak directly to SCA members, the individuals donating their material, about the SCA collection was education for both groups. We actually came home with new acquisitions including posters and towels for a conference in Miami during the early 80s.

The opportunity to present at the SCA conference was a highlight of my fall semester. Among my classmates, I have been one of the few to have had the opportunity to present at a conference for their job. I also learned more about the amount of preparation needed to create a professional level presentation, which is always needed! Stephanie and I created a nice PowerPoint presentation, which we both practiced numerous times including one final run on the day of paper sessions. On a more personal level, I have become quite knowledgeable about the history of SCA. It was wonderful and slightly bizarre to actually meet the individuals featured in the collection. I was starstruck a few times. I am very grateful for the opportunity to present on a project that has been a passion of mine. Next time you see a neon sign or a diner, stop and take a look around! You won’t regret it!