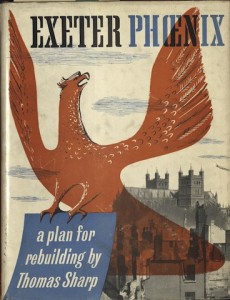

Sharp, Thomas. Exeter Phoenix: A Plan for Rebuilding. London: Published for the Exeter City Council by the Architectural Press, 1946.

Last week I encountered Thomas Sharp through his work, Cathedral City: A Plan for Durham (1945). I discovered that Special Collections houses several more of his proposals for English cities, to include Exeter, Oxford, Salisbury, Chichester, and Taunton. As I am not a planner or historian of modern architecture, I am unfamiliar with Sharp and his legacy. K. M. Stansfield attests to his influence:

Last week I encountered Thomas Sharp through his work, Cathedral City: A Plan for Durham (1945). I discovered that Special Collections houses several more of his proposals for English cities, to include Exeter, Oxford, Salisbury, Chichester, and Taunton. As I am not a planner or historian of modern architecture, I am unfamiliar with Sharp and his legacy. K. M. Stansfield attests to his influence:

He also produced The Anatomy of the Village (1946), which became a classic on the subject of village design, despite almost being suppressed by the ministry. In it Sharp for the first time consciously developed the concept of townscape, then almost unknown and still widely misunderstood, as a counterpart to landscape. It was a dramatic vision of the quality of urban space which he perfected, in outstanding analyses of historic towns, in his post-war plans—notably those for Durham, Oxford, Exeter, Salisbury, and Chichester, between 1943 and 1949. (Stansfield, “Sharp, Thomas Wilfred (1901–1978).”

As a medieval historian I connect with his approach to recognize the special character of each city and his desire to balance the needs of a modern city with its historic fabric, which was evident in his proposal for Exeter. He writes in Exeter Phoenix:

The planner’s first approach to his task is to sum up the personality of the city which has been put under his care. A city has the same right as a human patient to be regarded as an individual requiring personal attention rather than abstract advice. The second is that abstract principles of town planning do not in themselves produce a good plan. The good plan is that which will fulfil the struggle of the place to be itself, which satisfies what a long time ago used to be called the Genius of the Place. (pg. 11)

Sharp was faced with the challenge of not simply modernizing the fabric of Exeter but also rebuilding parts of the city due to both “blight and blitz” (pg. 82, 87). This challenge prompted Sharp to pose the question: Restoration or renewal? (pg. 87). He argues for “sympathetic renewal” –

It is one thing to attempt to save, and adapt to modern use, buildings which have actually survived from the past: it is quite another thing deliberately to imitate those buildings in new work. Such imitation must inevitably fail. It must fail because buildings are made of the spirit of their time as well as as of brick and timber and stone: and the spirit of the past cannot be recaptured… To attempt to rebuild 20th-century Exeter with mediæval forms would be the work of a generation that is visually blind and spiritually half dead.

…All things point, then, to the necessity for observing an appropriateness of scale and pattern in the renewal of the historical city. The sympathetic treatment of the surviving old buildings requires it. Sound planning for modern conditions of living requires it. It is upon this concept of renewal, in a way that is sympathetic to but not imitative of the old city, that this present plan for the rebuilding of central Exeter is based. (pg. 87-89)

Stansfield, K. M. “Sharp, Thomas Wilfred (1901–1978),” rev. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004. Accessed 12 June 2015. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/31673.