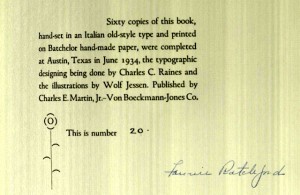

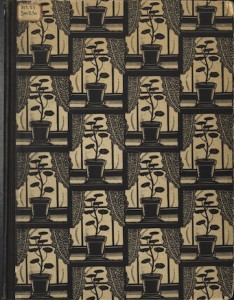

Brontë, Emily. Two Poems: Love’s Rebuke and Remembrance. With the Gondals Background of her Poems and Novel by Fannie Elizabeth Ratchford. Austin, Texas: Charles E. Martin, Jr.- Von Boeckmann-Jones Co., 1934.

Wait, Emily Brontë at the APL?

Occasionally, I find books in Special Collections that take me by surprise. Two Poems: Love’s Rebuke and Remembrance by Emily Brontë begs the question- Why do we have it. Upon opening the work, I discovered a tipped in watercolor signed by Wolf Jessen. There was also a card paper-clipped to end paper with the following text:

This is the only copy of this book at TxU. It might be considered a rare book because of its associations with Austin and The University, and should not circulate, or should circulate only on a very limited basis. It is a limited edition (no. 20 of 60 copies) published in Austin, with background material by Fannie Elizabeth Ratchford (former rare books librarian), illustrations by Wolf Jessen (Austin architect), and is dedicated “To Mrs. Miriam Lutcher Stark.

I needed to know more.

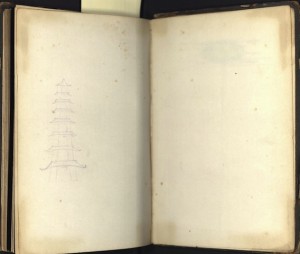

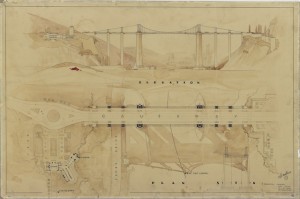

I began naturally with Katie Pierce Meyer, APL’s librarian, and Nancy Sparrow from the Alexander Architectural Archives. Nancy sent me the biographies for Wolf and Harold Jessen. The brothers were both students of architecture at UT and opened a firm together here in Austin in 1938. Wolf Jessen was also a member of the faulty at the School. Nancy also sent along one of Wolf Jessen’s projects, Monumental Causeway, which he produced while still a student (dated October 4, 1935).

The illustrations he made for Two Poems were also undertaken while he was a student!

While I had discovered who Wolf Jessen was, I was still curious about Fannie Elizabeth Ratchford, whose biography I located on the Texas State Historical Association website, which discussed her work with the Wrenn Library and scholarship on the Brontës (Leach, “Ratchford, Fannie Elizabeth”). She also had an interest in architecture. The Texas State Archives houses a collection of papers from Ratchford regarding an unrealized book project on Texas architecture, which she worked on between 1933-1947.

I also located a book review for Two Poems written by Leicester Bradner. I had hoped that Bradner would discuss the book project; however, he focuses on the argument Ratchford presents. He does note, “In spite of the brevity of the present study, which was designed by the publishers only for a collector’s item, it adds immensely to our understanding of Emily’s poems” (Bradner, “Reviewed Work,” 210). While Bradner makes no reference to Jessen, he does highlight that the work was a special edition at the request of the publisher, which raises intriguing questions about the genius and development of the book project.

Finally, I would note that APL’s copy of Two Poems is not the only copy on campus anymore. The HRC has two as well. One is unnumbered according to the record, while the second belonged to Miriam Lutcher Stark and is copy 1 of 20.

Bradner, Leicester. “Reviewed Work.” Review of Reviewed Work: Two Poems by Emily Brontë: With the Gondal Background of Her Poems and Novel by Fannie Elizabeth Ratchford, Emily Brontë. Modern Philology 33.2 (1935): 209-210.

Leach, Sally Sparks. “RATCHFORD, FANNIE ELIZABETH.” Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fra42). Accessed September 22, 2015. Uploaded on June 15, 2010. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.