Since I have not been able to post the last two Fridays, I am over sharing today! There is no theme that connects my selections- just things that struck my fancy. As I have noted before, I rely on serendipity – I browse but rarely with a focused intention. I think it unlikely that I would have found these works starting with the catalog.

Berlepsch-Valendas, Hans Eduard von. Bauernhaus und Arbeiterwohnung in England: Eine Reisestudie von H. E. Berlepsch Valendas, B.D.A. Stuttgart: J. Engelhorn, [1907].

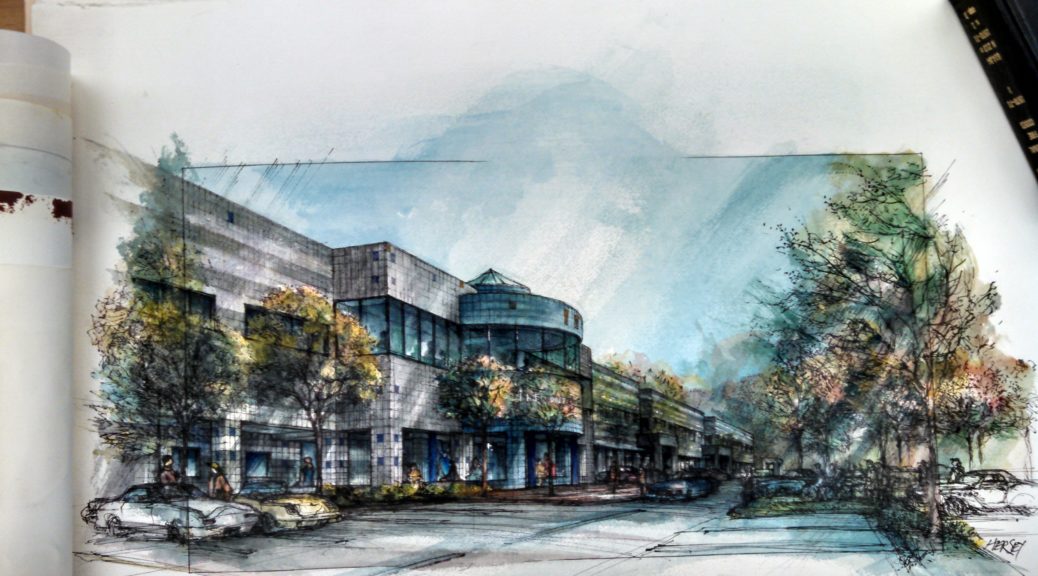

I was rather struck by graphic print on the cover. Berlepsch-Valendas documented the domestic architecture of Bournville and Port Sunlight, England near Birmingham and Liverpool, respectively. The text is written in German, so my ability to engage with it is limited. He includes photographs and plans of the towns. The second half of the work is the real treat. There are twenty plates with drawings documenting the architecture Berslepsch-Valendas encountered. The attention to detail is quite lovely.

Thomas, Rose Haig. Stone Gardens with Practical Hints on the Paving and Planting of Them; Together with Thirteen Original Designs and a Plan of the Vestal Virgin’s Atrium in Rome. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent and Co., LTD., 1905.

Again the cover caught my eye. I rather liked the graphic representations of the gardens, both on the cover and the plates within, and endpapers.

Rose Haig Thomas writes:

A FLAT stone garden costs not a little trouble and, if far from stone quarries, not a little money to make. But the reward is great, for it is a means of growing many tiny plants that would be hidden in the herbaceous border, and lost in a rock garden. In the stone garden each plant grows by itself, and thus its ways and habit of growth can be so much better observed, for there one may wander and enjoy the companionship of plants at those seasons of the year when in our damp climate the lawn is objectionable with the mists and heavy dews of autumn and winter. (pg. 7)

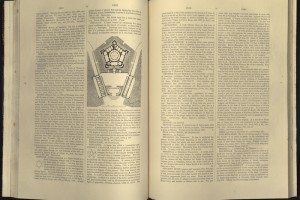

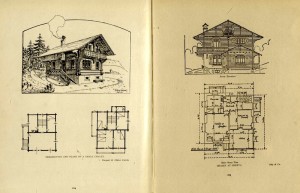

Prokop, August. Über Österreichische Alpen-Hotels, mit Besonderer Berücksichtigung Tirol’s. Wien, Im Commissionsverlag von Spielhagen & Schurich,1897.

Again the text is written in German; however, the documentation of the hotels and the natural landscape is quite useful. Prokop included drawings- sections, elevations, plans, details, and perspectives- and photographs, both of the structures and the dramatic views of the mountains. The work would be quite useful for those interested in nineteenth-century hotels. Many of the hotels are of the rustic lodge variety; however, some are more classically inspired.

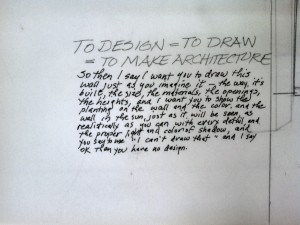

The title of this book struck me initially- which on the spine is just Tudor Domestic Architecture Reviews- because I have been watching Wolf Hall on PBS. It was not at all what I was expecting. It is truly a scrapbook of items related to The Domestic Architecture of England during the Tudor Period; Illustrated in a Series of Photographs & Measured Drawings of Country Mansions, Manor Houses and Smaller Buildings with Historical and Descriptive Text by Thomas Garner and Arthur Stratton.

Someone carefully collected the press releases and reviews of the publication and pasted them into this book. He hand wrote page numbers and a table of contents and marked in pencil sections of the reviews, which primarily date from 1908-1912. In an inside pocket, the collector stashed a few other related items, including a handmade mock-up of the title page. There is no record of the creator of the scrapbook.

Curious about the publication itself, I found a two volume set published in 1911. Our copy came to us with the Ayres and Ayres archive. On the inside cover, a couple of quick sketches were drawn, which is always a favorite find.