Charles Jencks. The Scottish Parliament. London: Scala, 2005. Christopher Hussey. The Work of Sir Robert Lorimer, K.B.E., R.S.A. London: Country Life Limited, 1931. Peter Savage. Lorimer and the Edinburgh Craft Designers. Edinburgh: Paul Harris Publishing, 1980.

I do not pretend to know enough about modern politics in the UK to have an opinion about the vote today in Scotland. I can though chat forever about 12th century politics and its effect on the architecture and landscapes of David I. However it should go, today’s post is for Scotland.

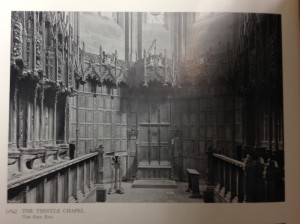

Of the modern Scottish architects, my heart belongs to Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his Glaswegian cohort. Having written previously about Mackintosh, I thought I would introduce two favorite places in Edinburgh: The Thistle Chapel by Sir Robert Lorimer and The Scottish Parliament by Enric Miralles.

I discovered Sir Robert Lorimer not in Scotland but rather in a class on the Arts and Crafts Movement. Charles Hussey writes of the chapel and Lorimer:

It is a remarkable, and was at the time a unique, example of a true revival of the medieval crafts- traditional yet spontaneous; instinct with the Gothic spirit yet unaffected and of its own age. Its triumphant success was owing primarily to Lorimer’s approach to architecture being essentially that of the medieval craftsman-architect… But that would not have sufficed had he not been in the fullest sense of the term an artist. (pg. 80)

While my studies had prepared me to anticipate what I would see in the chapel, I was overwhelmed by the space. I remember transitioning from the darkened cathedral to the brilliantly carved and light-filled chapel.

Unlike The Thistle Chapel, I actually knew nothing of The Scottish Parliament. I happened upon it on my trip to Holyrood Palace to see Holyrood Abbey, a David I foundation. I was surprised by the building as I walked along Canongate, a striking contrast to the street and Holyrood; however, it is nestled rather well into the landscape. I had no idea what would be in store when I decided to take the tour of the building. I remember feeling surprised at every turn. And I enjoyed walking the exterior whenever I happened to be nearby; there was always a new discovery to make.