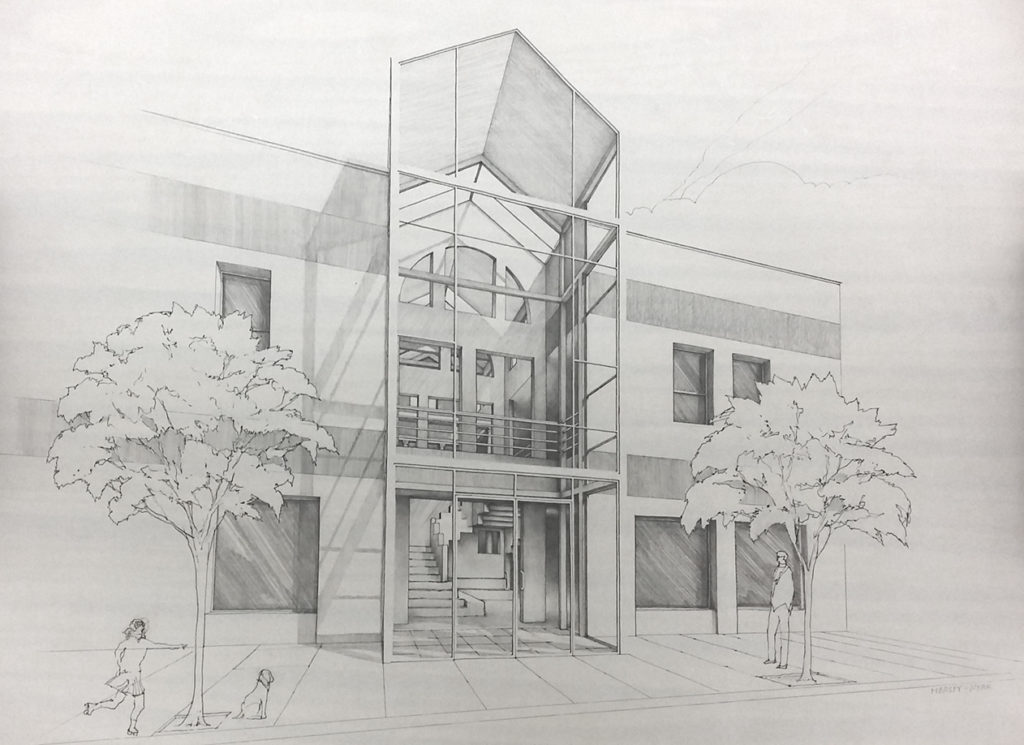

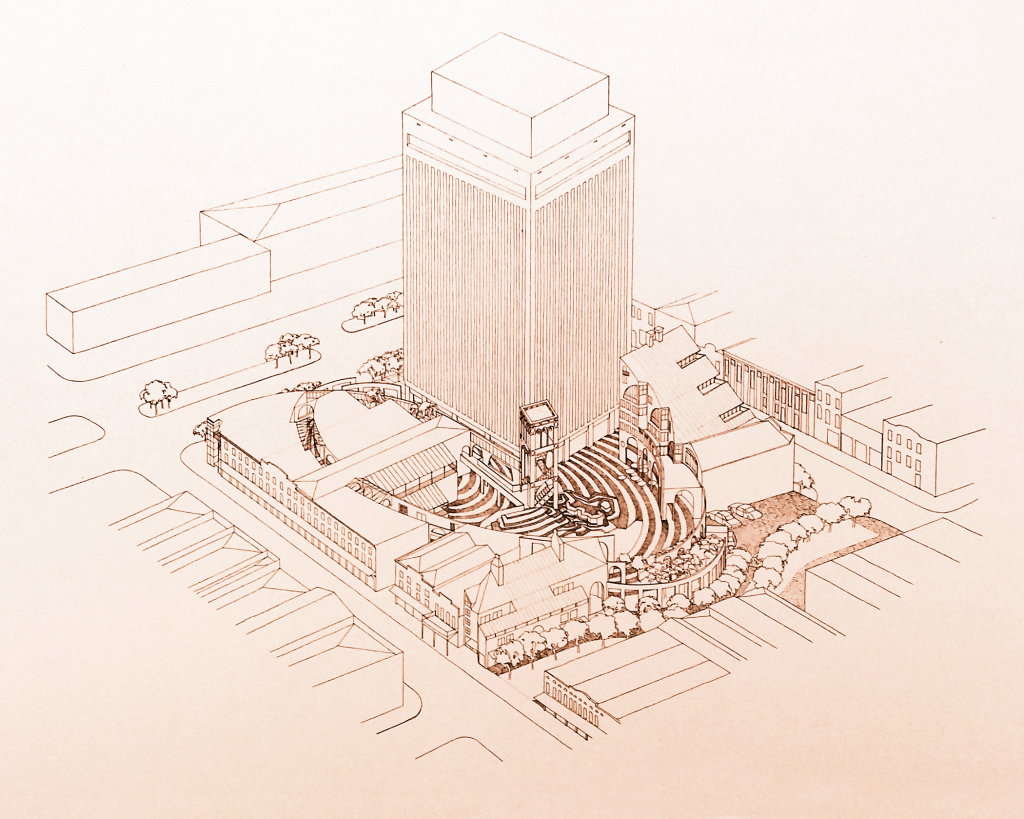

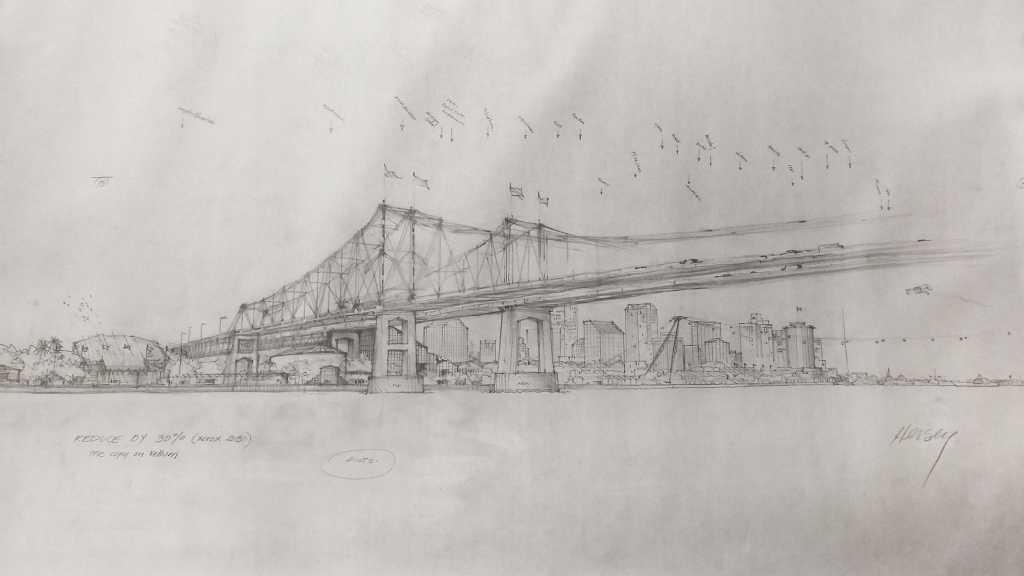

This is Kathleen Carter again with another update on the Anthony Alofsin archive processing. The Design Education materials have all been safely rehoused, so I’ve moved on to the Central European Architecture materials in the collection.

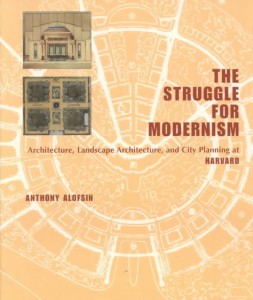

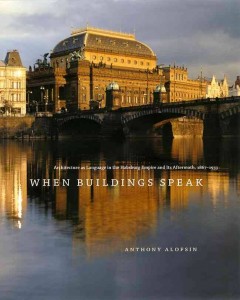

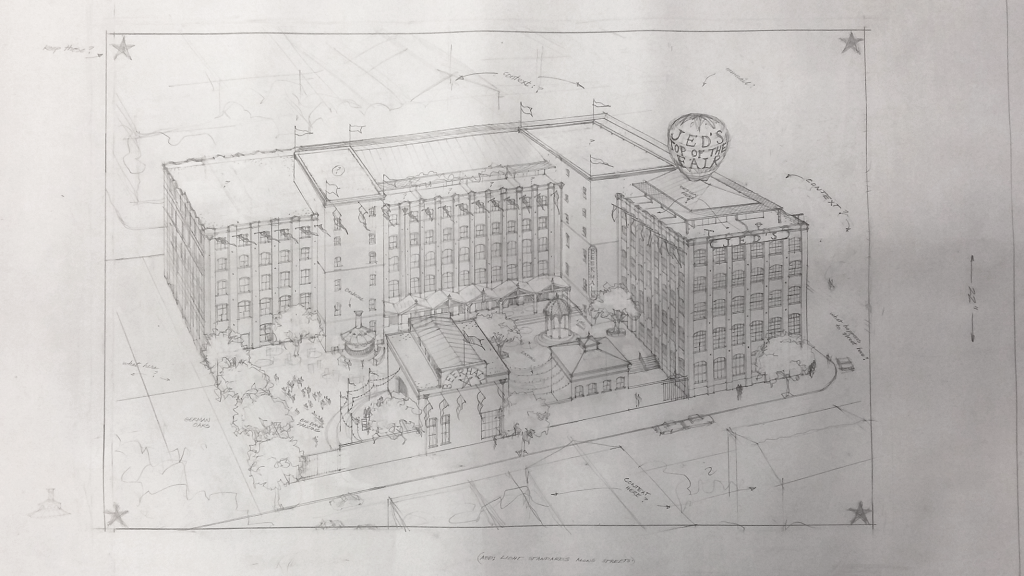

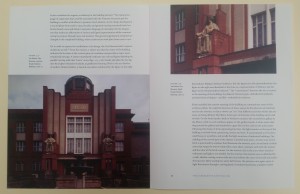

In the early 1990s, Dr. Alofsin led a team of scholars from all over the world in a research consortium called “A Tense Alliance: Architecture in the Habsburg Lands, 1893-1928.” The Tense Alliance research project was supported by the Internationales Forschungzenstrum Kulturewissenschafe (IFK) research institute in Vienna, the Getty Research Institute, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA). Scholars explored the role of architecture in Central Europe and the project resulted in an international traveling exhibition “Shaping the Great City: Modern Architecture in Central Europe, 1890-1937.” Alofsin independently continued his research from the Tense Alliance project and also wrote the book When Buildings Speak: Architecture as Language in the Habsburg Empire and Its Aftermath, 1867-1933 on emerging architectural styles of the late Austro-Hungarian Empire.

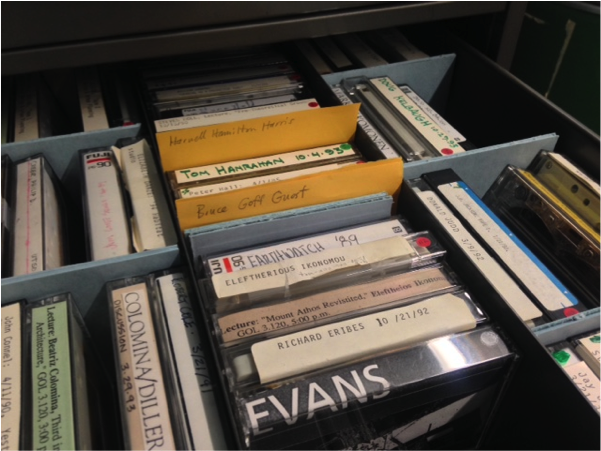

Both the field notes and research from the Tense Alliance project

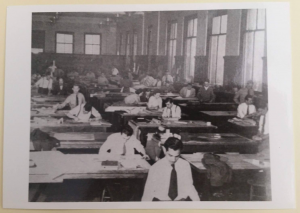

and Alofsin’s work on When Buildings Speak make up the Central European Architecture materials of the Anthony Alofsin archive. Alofsin also made a point to have beautiful color photography taken of the architecture explored in his book. As a result, not only do the Central European Architecture materials contain accumulated research and multiple drafts of When Buildings Speak, but also thousands of stunning visual materials including photos, transparencies, 35 mm slides, and negatives.

As with the Design Education materials, I have been rehousing these materials into new archival quality folders and boxes. I’ve also been at work adding the Central European Architecture materials to a draft of a finding aid of the collection. The finding aid will eventually provide researchers with a guide to all of the Alofsin materials. While carefully placing all of these photographs into protective sleeves and papers into new folders is time consuming work, it’s necessary for their long-term preservation, and the materials themselves are incredibly interesting and beautiful to see. I’ve really enjoyed both working with them and the knowledge that in the future others will be able to access them as well.