Though Katie has been with us for a few months now, we would like to officially extend a warm welcome to her! Katie is the interim Architecture & Planning Librarian, replacing Martha Gonzales-Palacios, who has transitioned to a new role at the University of Oregon.

Those of you that are familiar with the library may know Katie – she’s been ‘with’ us in a number of capacities throughout the last few years! Graduate Assistant Stephanie Phillips sat down with Katie to introduce her to all audiences through a Spotlight Interview.

Stephanie: Tell us about yourself! What is your educational background?

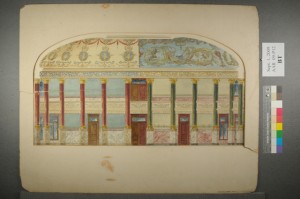

Katie: I received my undergraduate degree in Philosophy from Southwestern University; I have a Masters degrees from University of Texas at Austin in Information Studies (MSIS) and a masters in Architectural History from the UTSOA; I am currently back in the iSchool, working on PhD in Information Studies. My research focuses on complexity of contemporary workplace practices and the preservation of architectural artifacts.

S: What is your history with the Architecture and Planning Library? How did you find yourself in this position?

K: My first semester in graduate school, I did a group project at the Alexander Architectural Archive. I loved working with architectural records and convinced them to hire me; I worked at the archives since May 2006, processing architectural collections. Most recently, I was the project manager for the Charles Moore archives. When the interim Architecture and Planning Librarian position opened up, I thought is was a great chance to do more work in the library and connect with the UTSOA students, faculty, and staff.

S: How would you describe this position? What will you be doing?

K: I will provide reference, research support, and library instruction. It has been a busy semester. I’ve really enjoyed teaching library instruction sessions for undergrads and grad students.

S: What are you most excited for in your new position?

K: I am most excited about fostering collaboration between the UT Libraries and UTSOA as well as with the School of Information. I see the potential for exciting projects that bring together the expertise in the libraries, Architecture, and the iSchool.

S: What is your favorite book?

K: Einstein’s Dreams by Alan Lightman. My creative writing teacher gave it to me in high school and I try to re-read it every couple of years. It is a collection of short chapters, each on a different conception of time.

S: What are some of the best resources that the Architecture & Planning Library offers students?

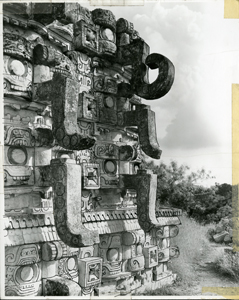

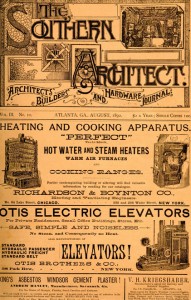

K: We are fortunate to have a dedicated Architecture and Planning Library in close proximity to the School of Architecture. The library has a great collection of books and periodicals, fantastic materials in our special collections, and the Alexander Architectural Archive; a great staff, which I consider a resource; and many more!

S: To put you on the spot – what is the most interesting thing about yourself?

K: Probably my travel experiences. I had an opportunity to travel to Sweden with Wilfred Wang and a group of architecture students a few years ago, while completing my Architectural History degree. I attended a Digital Humanities Observatory workshop in Dublin and did an internship with ICCROM in Rome. I have tried to take advantage of educational opportunities where I get to travel. Oh, and I love ziplining! We went to Costa Rica for our honeymoon, partially because of the ziplining.

Welcome, Katie! We’re so glad you’re here!