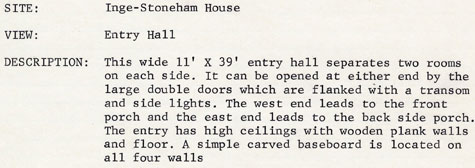

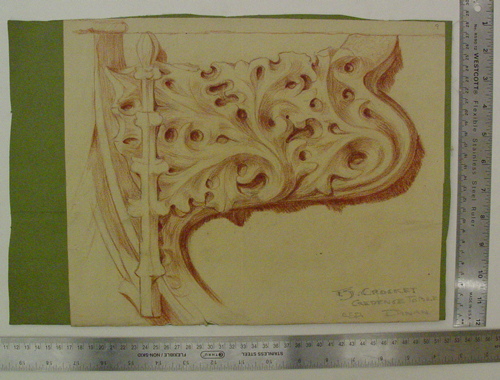

For many years now the Alexander Architectural Archive and iSchool lecturer and paper conservator Karen Pavelka have collaborated on preserving works on paper from the archive collections. Conservation students at the Kilgarlin Center for for the Preservation of the Cultural Record gain experience treating archival works as part of the Paper Laboratory taught by Pavelka. Second year Conservation student D. Jordan Berson describes his process of treating an early 20th century watercolor by Texas architect James Riely Gordon.

To see other images of this installation, visit the slide show on the Architecture & Planning Library flickr page.

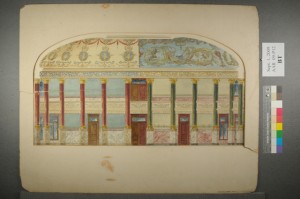

The goal of this treatment was to stabilize the fragile drawing in order to lift access restrictions and enable safe handling by researchers. It was also desired to reduce detracting visible damage. The object had tears and surface distortion, creases and a damaged acidic mat that was adhered directly to the artwork. It was evident that large areas of additional artwork were obscured by the existing mat. In addition, there were several areas along creases where the paint had been burnished or rubbed completely away, exposing the paper substrate.

The first part of the treatment was to mechanically remove the mat and adhesive residue as much as possible. Where residue remained adhered to the object, it was scraped away as possible by introducing very light amounts of moisture to soften it, then scraped away with a microspatula or wiped away with cotton swabs. This process took many hours. Then the piece was dry cleaned on both sides using soot sponges, and white eraser shavings. Tears were mended and splayed corners were consolidated using wheat starch paste. Thick Japanese tissue mending strips were glued down on the reverse side of creases to reduce planar distortion. Detracting media loss was remedied through inpainting. First a gelatin sizing was painted into the areas of loss, followed by inpainting with color-matched watercolors. Finally, a new acid-free mat was hand-cut using a Dexter mat-cutter. Instead of adhering it to the object as the old one was, a new “T-hinge” design was used that replicated the design of the original mat while enabling viewers to see the long-hidden artwork underneath.

To see other images of the treatment, visit the slide show on the Architecture & Planning Library flickr page.

Sustainable Architecture in Vorarlberg by Ulrich Dangel

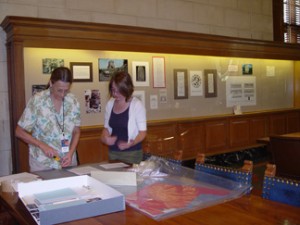

Sustainable Architecture in Vorarlberg by Ulrich Dangel reBILD installation at the Architecture & Planning Library Reading Room. To see full size image, click

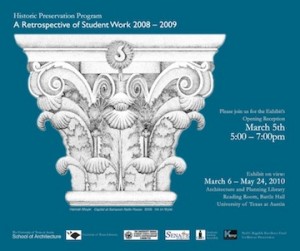

reBILD installation at the Architecture & Planning Library Reading Room. To see full size image, click  Historic Preservation Program: A Retrospective of Student Work, 2008-2009 exhibtion on view at the Architecture & Planning Library Reading Room. To see full size invitation, click

Historic Preservation Program: A Retrospective of Student Work, 2008-2009 exhibtion on view at the Architecture & Planning Library Reading Room. To see full size invitation, click