Hannah Stamier recently blogged about the Bon Marché and Émile Zola on ARTstor’s blog, highlighting images from their collection- which I remembered when I happened across some books on a similar topic. ARTstor is of course an excellent resource; however, I would also encourage you to explore the works in Special Collections on department stores and store fronts, if this topic is of interest. I pulled four books today as examples—

Dan, Horace. English Shop-Fronts, Old and New; A Series of Examples by Leading Architects, Selected and Specially Photographed, Together with Descriptive Notes and Illustrations, by Horace Dan, M.S.A. and E.C. Morgan Willmott, A.R.I.B.A. London: B. T. Batsford, 1907.

English Shop-Fronts is both a history of the building type and advice for designing anew. The first chapter discusses the history of early shop fronts, while chapter two, modern ones. The final chapter is a discussion of the practical aspects of the front: materials, glazing, lettering, lighting, and entrances, for example. Dan includes 52 plates, primarily from England and Scotland.

Geo. L. Mesker & Co. Store Fronts. Evansville, IN: The Company, 1911.

Unlike the other works that I selected today, Store Fronts is a catalog, produced by Mesker & Co. of Evansville, Indiana, from which a proprietor could select the design of a store front or other architectural details and materials. The catalog includes designs for concrete, brick, and galvanized iron fronts along with cornices, stamped steel ceilings, and elevators.

Curious about the company itself, I found the website, Mesker Brothers, maintained by Darius Bryjka of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. The site includes a discussion about the facades, the company catalogs, and documentation of the store fronts by state.

Herbst, René. Modern French Shop-Fronts and their Interiors. with a Forward by James Burford. London: John Tiranti & Company, 1927.

Following a brief introduction, Modern French Shop-Fronts and their Interiors consists of 54 large plates. Herbst writes:

Our opinion is that a shop front should be sober and be composed almost exclusively of a dressing of its own pillars, or of a covering which dissimulates blinds, gratings, and lighting fixtures. It should, however, provide ample space for the sign and lettering which are important from the advertising point of view, yet everything should be subordinated to the merchandise itself- which should occupy the largest space and be displayed under a judicious lighting arrangement so as to focus the attention of the public. (Introduction)

For an example of Herbst’s work, see plate 17 from Magasins & Boutiques.

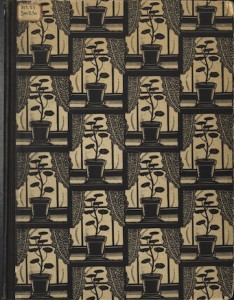

Lacroix, Boris J. Magasins & Boutiques. Paris: C. Massin [194-?].

Magasins & Boutiques is a collection of 36 plates of store fronts and interiors in Paris. Lacroix includes stores, boutiques, shops, and restaurants or bars. A very brief description accompanies the plates along with the name or the architect or decorator; however, dates have not been provided.

Daniel Ostroff notes in his introduction, “With the Eames files taking up more than 120 linear feet at the Library of Congress, the collected Writings of Charles and Ray Eames could easily fill 40 volumes. To make their writings as accessible as possible, I made the decision to limit my choices to a comprehensive selection that would fit one volume” (pg. xvi). Ostroff limited his collection both chronologically and thematically. The chronological frame is set between 1941 and 1986 with Ostroff identifying 1941 as a significant date for Charles and Ray Eames (pg. xvi). The selection of material also revolves around the theme of process. Ostroff writes, “This book is a guide to the Eames process: how, in their own words, they did what they did” (pg. xiii). Included in the anthology is both published and unpublished material as well as photographs, illustrations, and reproductions of letters and notes. My favorite reproduction is of a rebus for Lucia Eames, which begins with a drawing of a deer (pg. 199). You will have to stop in to see it!

Daniel Ostroff notes in his introduction, “With the Eames files taking up more than 120 linear feet at the Library of Congress, the collected Writings of Charles and Ray Eames could easily fill 40 volumes. To make their writings as accessible as possible, I made the decision to limit my choices to a comprehensive selection that would fit one volume” (pg. xvi). Ostroff limited his collection both chronologically and thematically. The chronological frame is set between 1941 and 1986 with Ostroff identifying 1941 as a significant date for Charles and Ray Eames (pg. xvi). The selection of material also revolves around the theme of process. Ostroff writes, “This book is a guide to the Eames process: how, in their own words, they did what they did” (pg. xiii). Included in the anthology is both published and unpublished material as well as photographs, illustrations, and reproductions of letters and notes. My favorite reproduction is of a rebus for Lucia Eames, which begins with a drawing of a deer (pg. 199). You will have to stop in to see it!